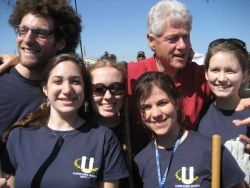

Commitments to start social-change initiatives and spirited discussions of global issues — these aren’t typical results of 700 college students heading to New Orleans during spring break season. But last weekend, students from a diverse group of colleges, several dozen university presidents, and prominent social change agents — not to mention Bill Clinton — spent a day and a half on Tulane University’s campus for Clinton Global Initiative University (with a cameo by Brad Pitt).

Commitments to start social-change initiatives and spirited discussions of global issues — these aren’t typical results of 700 college students heading to New Orleans during spring break season. But last weekend, students from a diverse group of colleges, several dozen university presidents, and prominent social change agents — not to mention Bill Clinton — spent a day and a half on Tulane University’s campus for Clinton Global Initiative University (with a cameo by Brad Pitt).

Trying to live-blog an event while you’re also trying to finish your senior thesis — not a good idea. Nonetheless, a belated report from the Clinton Global Initiative’s new youth event:

The pillars of the event were global issues like climate, poverty, health, and human rights. And over the course of the four times that Clinton addressed the group in more and less formal settings, it became clear, from the policy ideas he would riff on, that the issue on his mind these days is climate change. Like at grown-up CGI, each participant was intended to leave with a “commitment to action” in one of these areas. The approach lends itself to individualistic projects like raising money for a school in a developing country, or to starting a local micro-finance effort in the rural U.S.

At CGIU, it was abundantly clear that Kyle Taylor, a young “social entrepreneur,” was entirely correct when he was quoted in a recent New York Times Magazine saying, “Our generation is replacing signs and protest with individual actions.” Eerily so … and for better or worse, I’m inclined to add. It’s an approach far from the campaigns to change the policies of — or even shut down — international financial institutions that were all the rage when I first got engaged in these issues. But my peers’ inclination to propose small-scale (and to be fair, potentially scalable) solutions that poke at the intractable global problems that our political leaders fail spectacularly to address — rather than rally to protest these leaders — is not without its merits.

As hundreds of young people outfitted in CGIU T-shirts did a morning of service work in the Ninth Ward, clearing dirt and debris where Brad Pitt and Bill McDonough’s Make It Right project will soon grow, I pondered how this became the dominant approach to change for “millenials” in America. (Consider: Would several hundred European youth address social welfare issues by clearing off sidewalks? It’s more likely they’d be digging up the sidewalk cobblestones to throw at riot cops.)

As hundreds of young people outfitted in CGIU T-shirts did a morning of service work in the Ninth Ward, clearing dirt and debris where Brad Pitt and Bill McDonough’s Make It Right project will soon grow, I pondered how this became the dominant approach to change for “millenials” in America. (Consider: Would several hundred European youth address social welfare issues by clearing off sidewalks? It’s more likely they’d be digging up the sidewalk cobblestones to throw at riot cops.)

A full exploration of this phenomenon would take more than a blog post, but I think it has something to do with Reagan telling America that government couldn’t solve our problems, and the George W. Bush years confirming that corporate America wasn’t going to, either. What’s left but to do things yourself, from the ground up?

During the event, Clinton seemed to catch on to the limitations, or at least the peculiarities, of this apolitical approach to change. He queried speakers on the panels he moderated about how they thought hands-on service projects should interact with initiatives for policy changes. I didn’t hear a good answer from any of them, and I’m unsure if Clinton thought he did either, because he kept asking. I hope that Clinton’s questions provoked some reflection in the audience, and that my peers catch on — sooner rather than later — to the ways that direct service work can, and must, complement the policy and market changes that can ultimately solve global problems. It’s through volunteer and direct service, among other things, that we can engage the base of people needed to call for policy change on any of these four global issues. Once we have that base, though, it has to be applied as political pressure, or service efforts will remain only Band-Aids.

On the other hand, the biggest thing I think these young people deserve credit for is seeing — far more intuitively than their forebears running NGOs — how global health, poverty, human rights, and climate issues are four peas in a really messed up pod. The apolitical approach taken by millenials may be related to the fact that these issues poll as high concerns for us, and they are apolitical issues themselves (although climate didn’t used to be). It is simply clear that these are the four greatest moral challenges we face today.

I give President Clinton credit for attempting to answer, in his post-presidency, the unanswered social and environmental questions that were raised, in a way, by his administration’s policies of economic globalization in the 1990s. In the closing remarks to the conference, he posited that an obligation to solve problems of climate change, poverty, and disease comes along with the interdependence that we enjoy every day in the form of global communication and trade. It was fascinating to hear the man who ushered the World Trade Organization into being in 1994 join a panel discussion on the role of local food in rebuilding a sustainable New Orleans.

But all this reflection on the event doesn’t detract from the fact that, on their own, all of these commitments to action are inspiring examples of the imagination and impatience of young people. These commitments to action are well-conceived and crucial interventions that are going to help innumerable people. They will take off even more if they gain long-term and institutional support from the university presidents who attended the event — as Clinton suggested when he said that schools should be branding themselves based on the social ventures they nurture. Check out the commitments for yourself (and watch webcasts of the event) here.

At the end of the day, former President Clinton and the Clinton Foundation have done something that doesn’t happen very often: They’ve put serious resources into supporting youth-led initiatives in an open-ended way. Because there is no real student-union movement in the U.S. or national student association of much size, forums like CGIU are few and far between. There’s much more that could be done to help young people with good ideas make them great and make them real.

For all that they depend on young people for energy and donations, most NGOs working in all of these issue areas do very little to fund, equip, train, and support leadership among young people outside of their own directed operations. Hopefully CGIU will be back, bigger and better, with more resources for young social entrepreneurs next year.

Commitments to start social-change initiatives and spirited discussions of global issues -- these aren't typical results of 700 college students heading to New Orleans during spring break season. But last weekend, students from a diverse group of colleges, several dozen university presidents, and prominent social change agents -- not to mention Bill Clinton -- spent a day and a half on Tulane University's campus for

Commitments to start social-change initiatives and spirited discussions of global issues -- these aren't typical results of 700 college students heading to New Orleans during spring break season. But last weekend, students from a diverse group of colleges, several dozen university presidents, and prominent social change agents -- not to mention Bill Clinton -- spent a day and a half on Tulane University's campus for