This story is published in collaboration with The Guardian.

For Daniel Delgado, the Fourth of July marked a turning point in 2020. It was the first holiday after COVID-19 had kept much of America locked down. In nine days, he’d be entering his 20s. He planned to spend his birthday relishing the Arizona sun with friends, but in the meantime, the holiday offered him an opportunity to be celebrated by family and friends, surrounded by love and human connection — things that had been hard to come by that year.

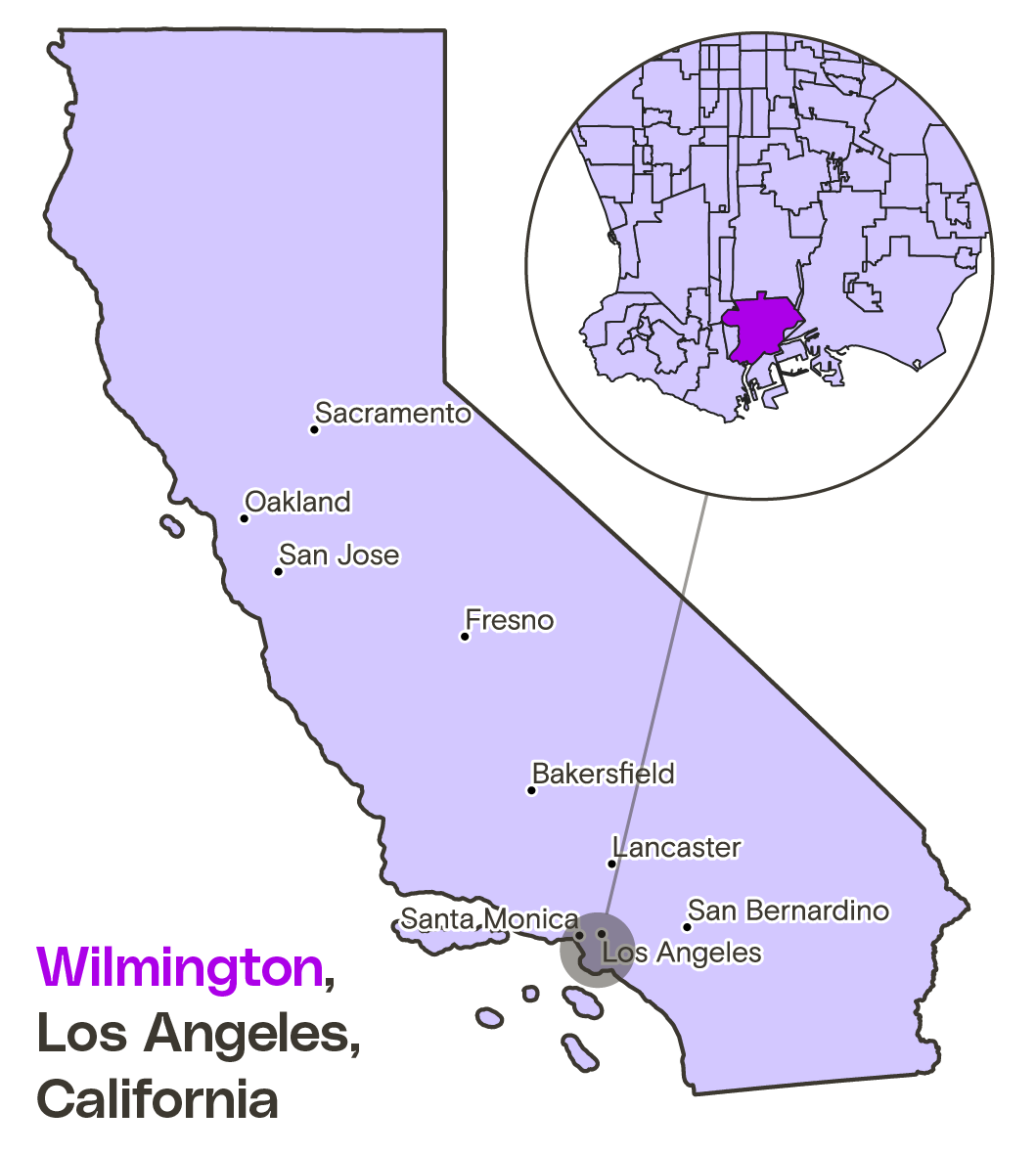

He spent the day at his aunt’s home in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Wilmington, California. His parents, Sonia Banales and Roberto Delgado, and his large extended family remember laughing, grilling ribs, and setting off fireworks.

Shortly after midnight, as the celebration died down, Delgado left the house to drive a few friends home. He never made it back.

At about 2 a.m., Delgado was shot and killed in the only place he ever called home, a small corner of Los Angeles tucked between the largest port in North America and the largest oil refinery in California. He was one of at least 160 people in the U.S. who lost their lives to gun violence that weekend. The exceptional deadliness of Independence Day weekend is one of the few American norms that the pandemic did not disrupt.

In the 20 months since Delgado’s death, his family has found little solace and fewer answers as they grapple with what happened that night. They’ve expressed disillusionment at the social support available to them; the police have not discovered a motive or firmly identified a suspect.

“We know that he didn’t deserve to die like this,” said Banales, Delgado’s mother. “It hurts so badly.”

“Every time I call [the police] they say, ‘I’m working on another case. I haven’t had time to work on Daniel’s case,’” she added.

Banales claims that the Los Angeles Police Department, or LAPD, has suggested to her that Delgado’s case has suffered due to “budget cuts” spurred by the historic protests against police violence the summer Delgado died. (While the LAPD’s budget was cut by $150 million in 2020, it then grew by $213 million in 2021, making it the city’s largest police budget in history.) LAPD representatives did not respond to requests for comment in time for the publication of this article.

Wilmington community members are no stranger to early death and the social inequality that drives it. The neighborhood is located in the Los Angeles city council district home to the most federal public housing projects and federally regulated toxic sites of all the city’s 15 districts.

The port in its backyard contributes to 1,200 premature deaths annually, and the air pollution from the refineries on its soil and trucks on its streets contributes to 4,100 premature deaths across Southern California. A lack of green spaces, jobs, and safe housing helps make its five most populous census tracts less healthy than 93 percent of the state, according to the California Healthy Places Index.

As structural and environmental damages have piled up, interpersonal violence has followed.

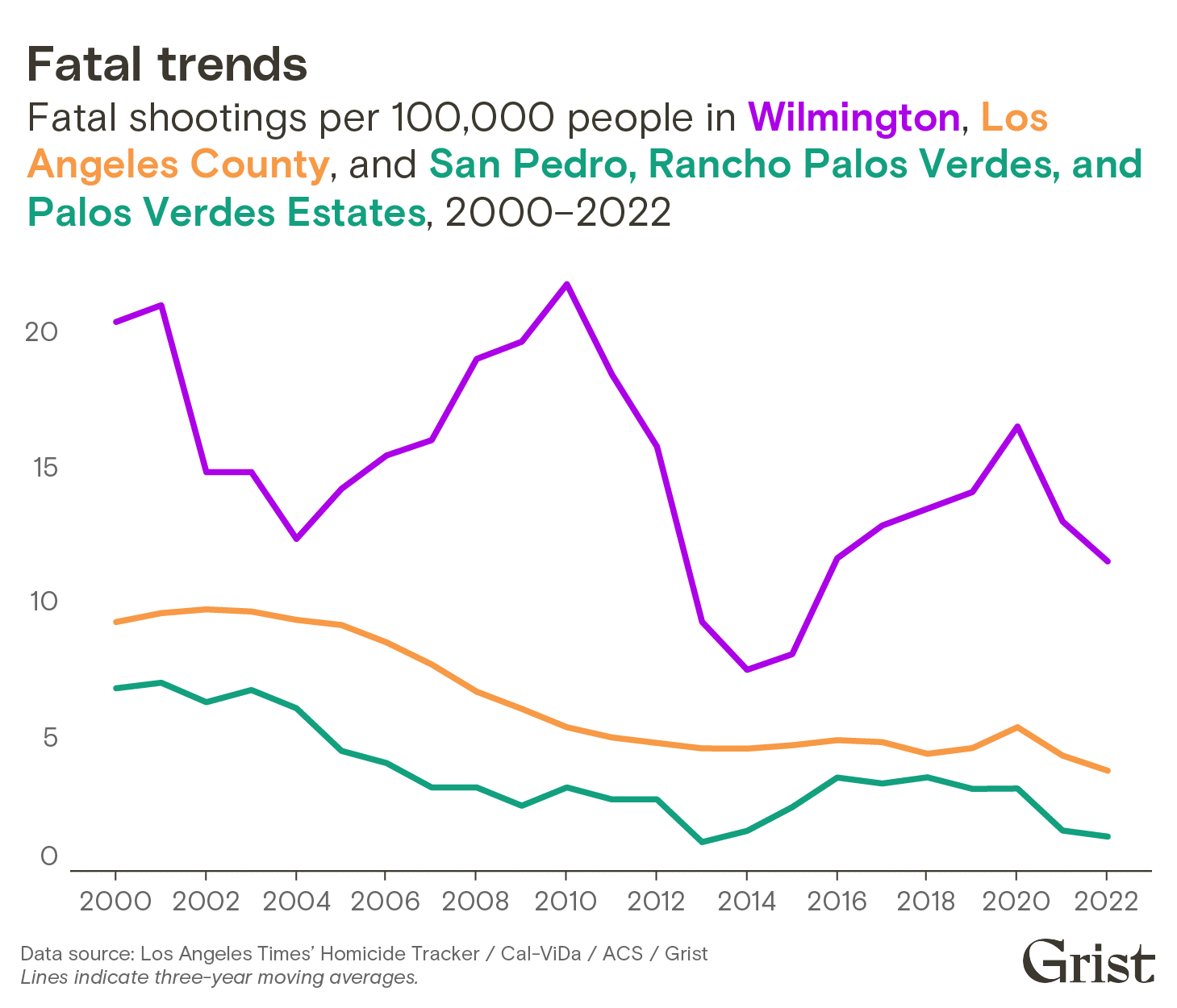

According to a Grist and Guardian analysis of California’s Department of Public Health reports and the Los Angeles Times’ homicide tracking database, at least 189 people have been shot and killed (10 of them by police) in the community of 55,000 since the year 2000. That amounts to nearly 2.5 times as many fatal shootings as the Los Angeles County per capita average and four times as many as those experienced in the cities that border Wilmington — San Pedro, Rancho Palos Verdes, and Palos Verdes Estates — over the same time period.

The vast majority of those shootings have taken place in the city’s industrial corridors, which are the West Coast’s main arteries for oil production, trucking, and logistics. They are home to more than 200 oil drilling sites, five fossil fuel refineries, three railways, and dozens of truckyards and scrapyards.

Delgado’s killing fits the trend: He was killed on the corner of Drumm Avenue and East Pacific Coast Highway, two streets flanked by shipping container overflow yards and metal scrapyards.

According to Southern California’s air pollution regulator, Wilmington is home to nearly 400 polluting sites, but their locations aren’t equally distributed. In 13 of the city’s 29 census blocks, where roughly 40 percent of the zip code’s residents live, there are just eight industrial sites. In the other 16 census tracts, there are nearly 370 industrial sites. Every single one of the community’s fatal shootings since 2000 has taken place in those industrialized tracts.

These inequities can be traced to America’s history of racist housing policies, including the practice of redlining. In the mid-20th century, the federal government considered roughly half of Wilmington’s residential area to be “hazardous,” which cemented its industrial character by maintaining low homeownership rates and paltry government support. The legacy of pollution and disinvestment persists, and it is also connected to the area’s rate of violence: Formerly redlined communities have significantly higher rates of gun violence than non-redlined neighborhoods.

Academic research on the relationship between pollution, land use, and violence has not definitively established a physiological relationship between pollution, access to green space, and violence and aggression. But it is known that air pollutants act as stressors, eliciting endocrine stress responses in our brains that lead to irrational decisions and violent tendencies and also disturb the physical, cognitive, and emotional health of people exposed to it at high levels. Meanwhile, research has shown a strong correlative relationship between violent crimes and air pollution levels — and that violence rises in communities that don’t have access to public green space.

In one study that combines environmental data with Los Angeles crime records between 2005 and 2013, researchers found that, even when controlled for many social, economic, and circumstantial variables (like weather), violent crime was 6.1 percent higher on days with dirty air than on days with clean air. In another study focused on Youngstown, Ohio, researchers found that turning vacant lots into community green spaces drastically decreased crime, including gun violence.

The research tends to support the “cues to care” theory — that if there is visible maintenance and care offered to shared spaces in communities, a feeling of security and social cohesion follows. The inclusion of natural landscapes, green spaces, and accessible outdoor community spaces helps mitigate the prevalence of violence, including gun violence, and pollution. Green spaces also help facilitate community interactions, which stifle interpersonal rifts.

Wilmington enjoys few such “cues to care,” especially compared to its neighbors to the south and southwest: Wilmington is home to three times less park space, relative to its size, than neighboring communities. Moreover, all but one of Wilmington’s green spaces are on land that is either a former industrial site or home to active and inactive oil wells, according to Los Angeles’ Zone Information and Map Access System. Since 2000, more than 100 times as many toxins — or 16 million more pounds — have been released into Wilmington’s air and water compared to its neighbors, according to data from the Environmental Protection Agency.

“The slow violence that drives death [in Wilmington] — pollution — has become accepted and normalized,” said Julie Sze, a professor of American studies at the University of California, Davis, who studies the connection between violence and pollution. “Then the fast violence — gun violence — is seen as normal.”

Wilmington’s current violence prevention strategies place a heavy emphasis on policing. While 27 percent of Los Angeles’s record-setting $11.2 billion budget for 2021 was allocated to the LAPD, less than 11 percent was allocated for transit, emergency management, neighborhood empowerment, community investment, housing, and creating more climate-resilient infrastructure.

Despite the prevalence of policing as a violence prevention strategy, data suggests that Wilmington residents do not utilize the massive resource. According to data shared by LAPD after a public records request, the department received just one single call for service due to shots being fired in the neighborhood between January 2019 and January 2022. Nearly 30 people were shot and killed in Wilmington over that same period.

“I think [policing] needs a lot of improvement,” said Roberto Delgado, Daniel’s father. “Someone took our son from us. They took everything from us, but there has been nothing done about it.”

Wilmington shows that there is an opportunity to expand the scope of public health interventions for violence prevention beyond individuals and into the physical environment, according to Octavio Ramirez, a community organizer and director of community gardens at the Wilmington-based Strength Based Community Change. Ramirez was born and raised in Wilmington. He plans to die there, too, but before that he wants to see a change.

“Growing up, I’ve noticed how a lot of things relate to each other here,” Ramirez said. “How the community being poorer means there aren’t as many good jobs; and how it being home to more renters means there’s not enough room for people; and how there not being enough places for people to relax outside leaves people agitated — how all this leads to more violence, more shootings.”

To fill the gaps that Ramirez has noticed in his community — and to build on skills that his dad, a gardener, passed on to him — he has turned his activism toward community gardening. With the support of his community organization, the local city council member’s office, and grants from local refineries (which he admits is ironic given the industry’s impact on public health in his hometown), Ramirez hopes the “Heart of the Harbor” garden, which is located in one of Wilmington’s top five hot spots for gun violence, will open doors for a trapped community.

“At the bare minimum, this community garden provides a place for people to relax,” he said. “But what I really hope it does is provide a place for people to build community, learn how to grow their own food, and feel connected to each other and our home.”

The 1-acre garden, home to 66 raised beds which can be rented by community members for $10 per month, also includes a public kitchen stocked with a state-of-the-art grill and stovetop, as well as a worm farm used for composting. In the coming year, it’s expected to expand to include a “food forest” with 80 to 120 fruit trees.

It’s the first step in a community-centered movement to reframe Wilmington residents’ realities, their access to the environment around them, and how they relate to each other, Ramirez says. He’s already seen a difference. The garden, and programs like it, are meant to provide sustainable models for reducing violent interactions that are community-led and do not rely on burdening victims.

“In a way [the garden] can help turn a very hostile environment into something really cool,” Ramirez said.

“A lot of people just don’t see opportunity here,” he added, “but I still have faith in my community.”

This article was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 Data Fellowship.