Infrastructure! We’ve really got your attention now, right? Here’s the thing, though: It’s what makes modern life possible. Showers, cellphones, pizza delivery, toilets — all those fail without infrastructure. Much of what we’ve got now is old, dangerous, and needs replacement, and voters of both political parties agree on the need to do something about it. (That last statement in itself should be shocking enough to keep you reading.)

So President Trump, seeking an issue slightly less divisive that yanking health care away from millions of people, has promised to present a $1 trillion spending proposal to Congress sometime in the next three weeks, claiming it will “completely fix America’s infrastructure.” Never mind that the American Society of Civil Engineers has said we need to spend $3.6 trillion by 2020 — they’ve obviously never seen Trump make deals.

The question is, where to start? Although Republicans and Democrats are united on the need to fix the nation’s roads, bridges, airports, and sewer drains, they largely disagree on how to spend the money — a split that’s largely rural-urban in nature, with Rs preferring highways and Ds preferring public transit, for starters.

As with his border wall, Trump has suggested he’ll get someone else to pay for the rebuilding effort — the builders themselves, who would be compensated in the form of tax write-offs and user fees. We talked to a lot of experts over the past few weeks, from both ends of the political spectrum, about where the money for infrastructure should go and how to pay for it. Just about all of them panned Trump’s ideas.

“When we look at our infrastructure investments, for the most part, they all lose money,” says Chuck Marohn, founder of the nonprofit Strong Towns. “So I’m deeply skeptical that, without financial shenanigans, there are any good investments out there for a business.”

What would get built under Trump’s let-it-pay-for-itself plan? A bunch of toll plazas, basically, Marohn says. So, instead of asking what will happen under Trump’s infrastructure proposal (sigh), we asked the wide range of experts we talked to what should happen. What would they do with $1 trillion to spend on the country’s corroded pipes, crumbling bridges, and iffy transit systems? Here are their wishlists, as told to Grist.

Let people out of their cars

Lynn Richards, president and CEO, Congress for New Urbanism

Grist / Amelia Bates

When you look at infrastructure needs in the United States, we’re trillions and trillions behind where we need to be. We can’t afford to spend our money on infrastructure that just meets one objective.

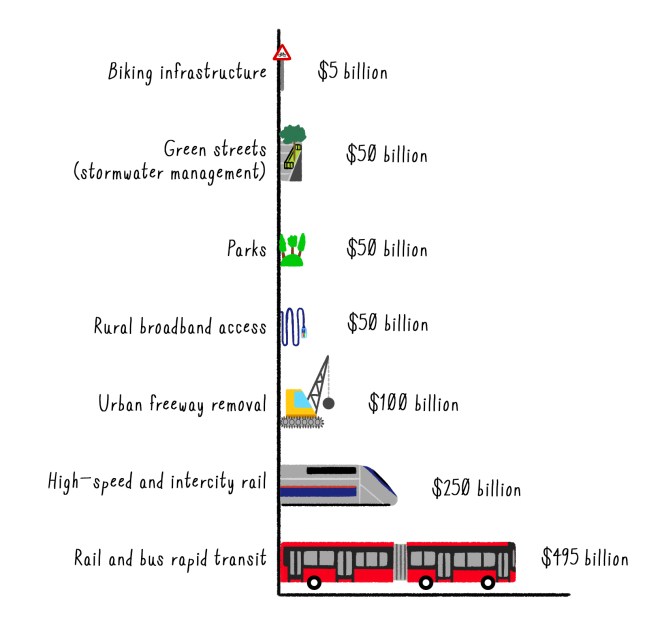

So my budget focuses on projects that fulfill multiple needs. Expanding biking infrastructure, green streets, and parks gives you a good return on investment and improves mobility and public health.

Let’s start with the smallest part of the budget: biking infrastructure. I bike from Georgetown to our office in DuPont Circle and often take up a whole car lane going 20 miles an hour max. Give bikers like me a protected lane, and you will not only make it easier for people to bike, but ease congestion.

People want mobility in the most efficient manner possible. But we make it so difficult to take transit, bike, and walk that of course people drive. It becomes the easiest way.

So many cities need more transit but aren’t ready for light rail. Let’s meet communities where they are. For some the answer is BRT, bus rapid transit. It looks and operates just like a rail system, but it’s cheaper and more flexible. Hartford, Connecticut, has been putting in miles and miles of BRT lines.

High-speed rail is an investment for the future even though we need it right now. It’s a seven-hour drive from Washington, D.C., to Boston and an eight-to-10-hour train ride. That should be a trip you can make on high-speed rail. Let’s link other major metropolitan areas, like New Orleans to Houston. We need to give people a wide range of transportation options.

There are freeways around the country that split neighborhoods and separate cities from the water, like the Alaskan Way Viaduct in Seattle, or I-81 in Syracuse. Many of these are nearing the end of their life. So instead of paying to repair them, take them down and create boulevards. The Embarcadero Freeway in San Francisco came down, and look at the boulevard now.

Shutterstock / Nickolay Stanev

Let’s build parks in economically disadvantaged communities. We know from research that parks have a great economic impact, leaving aside the public health benefits. Infrastructure is more than just sewer and roads. It’s about the very foundation of our communities.

No more ribbon cuttings

Aaron Renn, senior fellow, Manhattan Institute

Grist / Amelia Bates

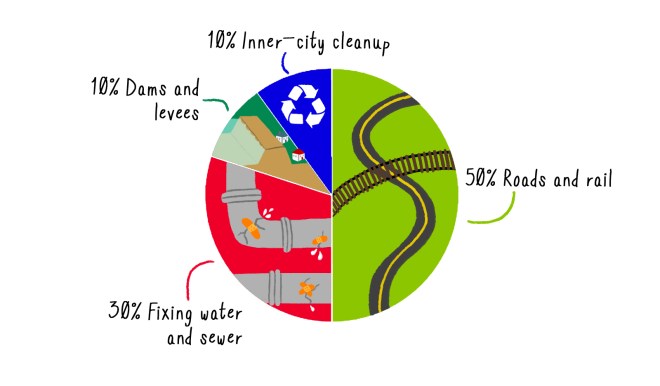

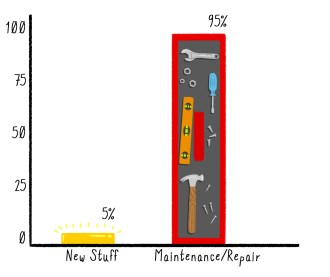

The most important principle of a federal infrastructure bill should be a maniacal focus on maintenance. Politicians always prefer cutting ribbons on new things to maintaining something that already exists. We put a large percentage into new roads and new transit systems when our old ones are falling apart. That doesn’t make a lot of sense.

I don’t favor building more highways. That’s not a national economic driver the way the original interstate highways system was back in the ’50s. A lot of people think we can build our way to prosperity. Look at China, people say. Well, China didn’t have infrastructure before.

To the extent that we need to spend on roads, there could be a stimulus-style, one-time grant program for roadways designed specifically to repair crumbling local streets and structurally deficient bridges. Local streets are where people live, and so many of them are in bad shape, but for the most part they’re not eligible for federal aid. Toledo, Ohio, estimates that it has $1.3 billion in needed repairs. Is Toledo better off with moonscape streets?

REUTERS/Joshua Roberts

I’m not interested in reducing transit funding. But a lot of money goes to dubious projects in cities that aren’t a great fit: They don’t have the density, the big downtowns; $3.3 billion for the Durham-Orange light rail project in North Carolina makes no sense. The money should go where there’s established transit — San Francisco, Chicago, New York City; otherwise, you risk losing ridership. The metro in Washington, D.C., is losing ridership because it’s breaking down all the time.

The federal government used to have a grantmaking program for water and sewer retrofits, but it was eliminated long ago. The post-industrial cities Trump championed are precisely the places where much of the nation’s obsolete water and sewer infrastructure is located. The federal government is telling them to make repairs. Cleveland, for instance, is spending $2.7 billion to retrofit its sewers for Clean Water Act compliance. That’s the most expensive capital project in the region.

People in struggling post-industrial cities are taxing themselves to pay for necessary repairs. And many of these people are poor.

Let the locals decide

Stephanie Gidigbi, senior advisor for urban solutions, NRDC

Grist / Amelia Bates

If the public is going to spend money, it must lead to good outcomes for the public. That hasn’t always been the case.

When we are thinking about some of the shovel-ready projects, we need to ask: Have we truly thought about the next generation of people that they will serve? Some of these plans have been on the books for decades. After all that time, do those plans still align with what that community looks like right now, and what is coming up?

We are literally living on what is 1960s infrastructure — it qualifies for AARP! When it was built, this was a different world. There weren’t civil rights laws in place, and infrastructure often reinforced inequities. Today, even as we talk about those inequities, we are, for example, reinforcing some of those highways that divided communities and continue to exacerbate the divide we see in America.

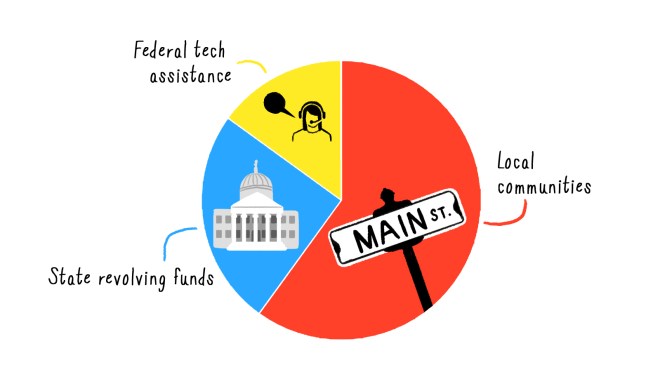

The majority of money should go to local communities — as local as possible. You can go to any city, any bar, and you can find someone who knows what needs to be fixed. When the money goes lower down — rather than stopping at the state governor’s level — it allows communities to ask for what they really need.

I’d say 25 to 35 percent should go to the state level for fully funding programs we know work well: Making sure state revolving funds for clean water and drinking water are fully funded. That will alleviate situations like what’s happening in Flint.

We still need some money at the federal level. Small communities know what they need, but they also need technical assistance — staff support and oversight — like the support that the EPA provides to communities that want to clean up brownfields.

In all of this, instead of using outdated building materials, use cleaner and greener materials. It may cost more upfront, but the benefits last longer and outweigh the costs over time.

Build housing, not transportation

Yonah Freemark, founder of The Transport Politic and PhD student at MIT

Grist / Amelia Bates

Over the past 30 years, American cities have spent billions on the expansion of their transit systems. Of the 30 largest U.S. metropolitan areas, 27 have some sort of urban rail network in operation — but in 1989, only 14 did. We’ve collectively spent huge amounts of money making transit systems larger. And yet the share of commuters using transit to get to work is the same nationwide now as it was in 1990 — and the share of people walking or carpooling to work has declined considerably. What gives?

Fundamentally, we’re bad at using the transit we have. Per-mile ridership on recent American light rail lines in mid-sized cities, for example, is typically a third of that on similar French tramways. At the heart of the problem is that the land uses around our transit stations are typically at a very low density, and driving is encouraged through required-parking provisions. What’s made the problem worse is the fact that we’ve spent even more expanding the freeway network. In the end, we’ve thrown a ton of money at our transportation system to make it less environmentally friendly.

If we’re going to spend a trillion dollars, let’s focus on intensifying land uses around existing transportation infrastructure, not expanding it. Cities around the country are suffering from a tremendous housing affordability crisis for working and middle-class households — why not find ways both to reduce their housing and transportation costs?

Rather than investing in new transit or highways, let’s provide cities with grants to support a massive boom in housing for low- and middle-income families around transit stations. Let’s encourage little downtowns of high-rise, mixed-use, green buildings. Not only will this investment produce more affordable housing, but it will make our transit systems more effective and get more people out of their cars.

Fix it first

Charles Marohn, founder and president of the nonprofit Strong Towns

Grist / Amelia Bates

Grist / Amelia Bates

Right now we have this huge maintenance backlog. We have this stuff rotting in the sun. Are we going to let it rot while we build a bunch more? That’s just reckless.

We’ve built an entire economy around large-scale infrastructure that ends up costing cities. So first you put in a road and a frontage road, and sewer and water, and what you get is a Walmart and a Costco and a housing development. The problem is that then we have a bunch of infrastructure to maintain, and that often costs more than the tax revenue that comes in from those new buildings. It’s not viable. We’ve been building infrastructure this way for two generations, and it’s slowly bankrupting our cities, towns, and neighborhoods.

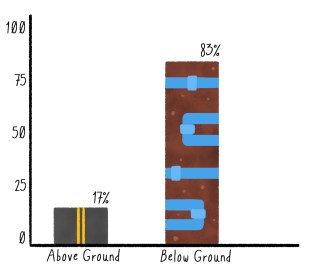

Instead of building new things, we need maintenance, mostly in older, poorer neighborhoods and mostly below ground. Many of our sewer and water systems are approaching 100 years old. When these core pipes fail, the problems cascade throughout the system.

The neighborhoods that have the highest tax return per acre today — and where a little bit of investment could have a big payoff — are the places with the highest poverty. So you look at those neighborhoods, and what do they need? They need just a little bit of love. Patch the sidewalks. Repave the streets. Fix the pipes. They also need new infrastructure. I’d put about 5 percent into what I would call neighborhood venture capital: Small, experimental projects: Put in some street trees. Put in a crosswalk. Connect to commercial centers.

I think the modern environmentalist needs to be a pro-city person, but our pattern of infrastructure investment hurts cities. It induces people to spend their money inefficiently, by getting on the freeway to go to Walmart rather than walking to a store across the street. The more we can invest in making cities viable places — places where people want to live, places that can take care of themselves — the more cities will serve the aims of environmentalists.

(Read more detail from Marohn here.)