Each day, Catherine Caldwell hauls three gallons of bottled water to her bathroom and two to her kitchen. She and her family use the water for flushing the toilet, washing hands, and — after heating it on the stove — cleaning dishes and cooking. For bathing, they head to her mother-in-law’s house a few blocks away.

The 44-year-old Caldwell, her husband, and two young grandchildren have been living without running water in their Detroit home for over four months. Every two weeks, they receive a delivery of water from a local nonprofit, We the People of Detroit. It’s the second time they’ve been without water services in the three years they’ve lived at the current residence. The short of it is this: They can’t afford to pay the bill, and the water company shut off their water.

YES!/Jennifer Luxton

Stories like Caldwell’s are common in Detroit. The city has a 40 percent poverty rate, and residents have seen water bills double over the past 10 years. But more often now, it’s not just Detroit; stories of people living without water are coming from other cities — Toledo, Ohio; Baltimore; and Houston. In Philadelphia, 4 out of 10 water accounts are past due. Two years ago, a survey of 30 major U.S. cities found that water bills rose by 41 percent between 2010 and 2015. The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that the average American family of four uses about 400 gallons of water a day, and that households should expect to pay 4.5 percent of their income on water.

As water poverty increases, cities have to decide what to do when people can’t pay their bills.

A recent study predicts that in the next five years, more than one-third of Americans will not be able to afford their water. The authors, Michigan State University professors Elizabeth A. Mack and Sarah Wrase, warned that the days of affordable water are coming to an end for most communities, from rural to urban.

YES!/Jennifer Luxton

Different cities deal with different water issues. Decaying infrastructure contaminates or leaks water. Climate change conditions make water more scarce. Conservation and efficient technologies mean less demand for water. Each of these factors drives up the rate. And then there’s this: When low-income families can’t afford their bills, cities raise rates even more to cover losses. (That puts middle-income people at risk for unaffordable water bills, too.)

“The percentage of U.S. households who will find water bills unaffordable could triple from 11.9 percent to 35.6 percent,” the study says.

In Detroit, where 50,000 households have lost water access since 2014, the water authority shuts off the water for residents who can’t pay. This is one reason the city finds itself at the leading edge of policymaking on water affordability. To prepare for what everyone will face within five years, the nation’s cities need only to look at Detroit.

YES!/Jennifer Luxton

Today, between 10,000 and 20,000 homes in Detroit are without water.

Detroit lawyers joined with other lawyers around the country to fight the mass shutoffs three years ago, and the coalition is now working on a national water rights policy. The “Civil Rights Bill for Water” would guarantee that no one goes without running water, regardless of their financial status.

Civil rights attorney Alice Jennings worked on a class action lawsuit in 2014 that managed to stop the shutoffs for about five weeks. They won some concessions, like more notice before a shutoff and more flexible payment arrangements. But it’s simply not enough, Jennings says, who’s based in Detroit.

“We’re looking for something that’s completely different,” she says.

The Civil Rights Bill for Water states the cost of water should be based upon a person’s ability to pay. It also stipulates a protected class: families with young children, senior citizens, and the disabled. No matter what, their water cannot be interrupted.

YES!/Jennifer Luxton

The proposal for the national policy will be submitted to Rep. John Conyers, a Michigan Democrat, in mid-April, Jennings says, but the group is realistic about its chances. “We do understand that we’re dealing right now in a political climate where this is not going to necessarily be passed this year or next year, or even five years from now,” she says. “I’m reminded of congressperson Conyers, who reintroduced the Martin Luther King Bill for 15 years straight before Dr. Martin Luther King’s birthday was declared [a national holiday].”

Jennings knows it may require a generational process of informing and educating to work out a viable policy, one that requires all 50 states to provide access to clean water for all residents, regardless of ability to pay.

Meanwhile, thousands of Detroiters are faced with monthly bills that can often be half their income, and people like Caldwell live in homes without running water.

The Michigan Legislature is looking at a new Michigan Water Is a Human Right bill package introduced in March. Until there’s a solution, community organizations like We the People have stepped in. Besides lobbying Detroit officials to adopt a water affordability plan, they supply water stations throughout neighborhoods, deliver water to homes, and staff hotlines for those with emergencies. They help residents negotiate with the water authority for payment arrangements. Some members have gone as far as paying a bill or two to prevent families from having children taken away by Child Protective Services because of unsanitary living conditions. They even support civil disobedience actions to obstruct shutoffs.

YES!/Jennifer Luxton

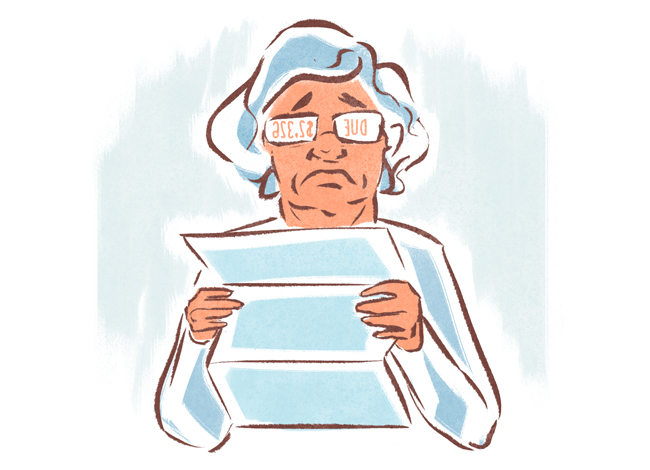

Caldwell takes care of two small grandchildren and relies on her husband’s modest income to pay the bills. After purchasing her house, she found out there was a delinquent water bill of $2,326.84. During the process to dispute the bill, her water was shut off. It’s been restored recently as she waits to find out whether she qualifies for a payment assistance program. If not, they’ll turn it off again.

Being without water can feel like a desperate situation.

When earlier attempts to get it turned back on failed, she took matters into her own hands, the way many Detroiters in her position have. She went to the hardware store, bought a special key, and just turned the water back on herself. It’s a felony charge with up to five years in prison. “I’m not gonna lie. I turned it on myself,” Caldwell confesses. “I can go to jail for that, I know that, but I got grandkids in here.”

YES!/Jennifer Luxton