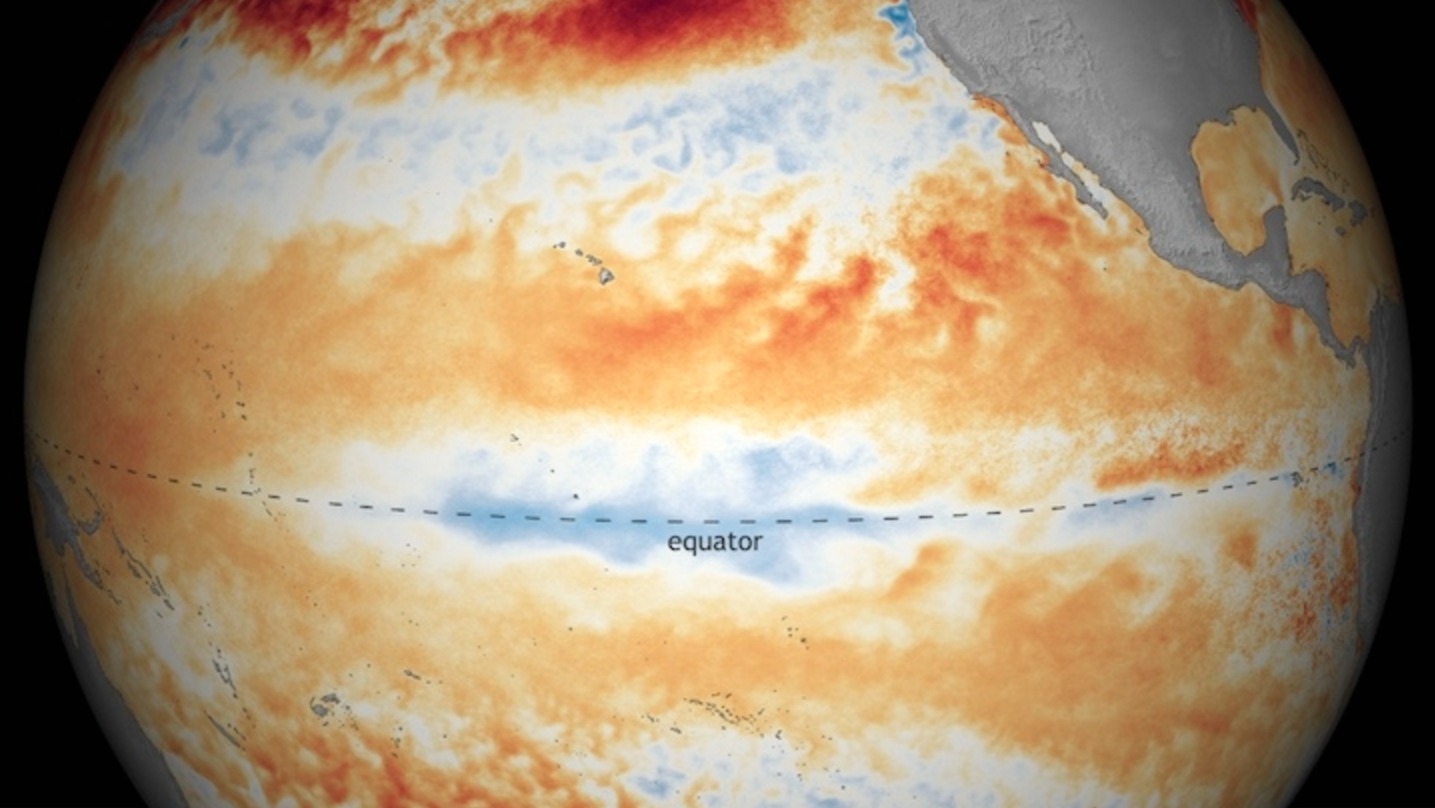

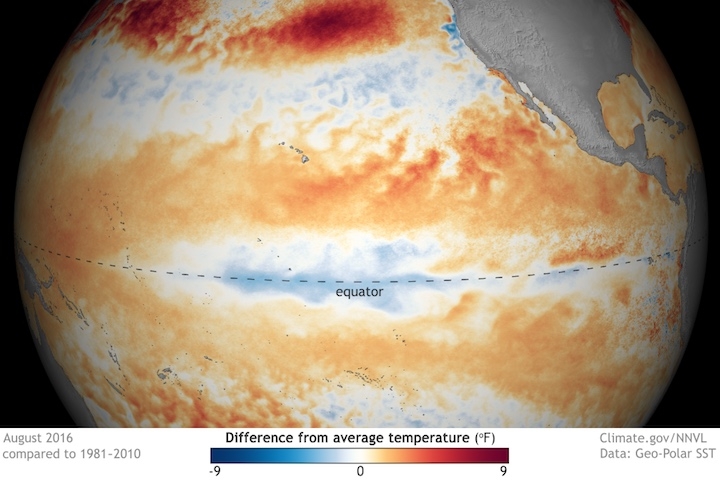

After the demise of El Niño, the climate phenomenon that has helped fuel record-setting heat for the past two years, all eyes have stayed on the Pacific waiting for its counterpart, La Niña.

Without the cooling influence of a La Niña event, the planet is likely to continue feeling the heat for the rest of the year. July and August tied for the hottest month ever recorded and 2016 is essentially guaranteed to be the hottest year on record.

So now after a few months of waiting for the arrival of La Niña, where do we stand? Well, that depends on who you ask.

According to the Japanese Meteorological Agency (JMA), La Niña has in fact arrived.

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology, another of the big tropical Pacific watchers, has a La Niña watch in place, but is still waiting for its “official” arrival.

But the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration dropped its La Niña watch last week, indicating that it’s unlikely that a La Niña will form this fall or winter.

All three agencies are looking at the same ocean, but have come to different conclusions about when — or even if — La Niña is going to happen. The main reason comes down to how you define La Niña.

For the average person, it just means cooler-than-normal ocean temperatures. But scientists are a little more precise than that. Let’s start with NOAA and why they’re feeling bearish on La Niña.

“We dropped our watch mainly because of the lack of model support for an extended duration of La Niña conditions that we need to see,” Michelle L’Heureux, a scientist at NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center, said.

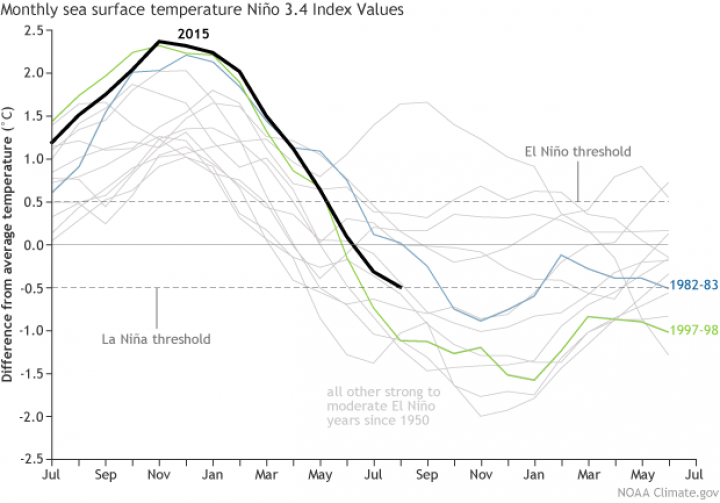

For NOAA to officially declare a La Niña, ocean temperatures in a specific region of the tropical Pacific (dubbed NINO3.4 for the hardcore nerds out there) need to be 0.9 degrees F (0.5 degrees C) below normal for five running three-month averages in a row (so September-November, October-December, and so on).

While it’s cooler than normal in that region right now (right on the edge of the La Niña threshold in fact), the models NOAA uses to look at the coming seasons just aren’t feeling the chill. Something similar happened after the super El Niño of 1982-83, so there is precedent, according to L’Heureux. She also stressed that it doesn’t mean NOAA has written off La Niña, but the odds of it are just less likely now.

The Bureau of Meteorology has even more stringent temperature guidelines for La Niña. Temperatures in the same region of the tropical Pacific need to be 1.55 degrees F (0.8 degrees C) below normal, though the bureau doesn’t have the running average requirement. It also uses a variety of models, similar to NOAA, but it weighs them differently. Its outlook still hints more strongly at a La Niña, hence the watch remains.

Then there’s JMA. It looks at another region of the Pacific (NINO3 for the nerds), where temperatures have been cool enough to declare a weak La Niña. There’s also a question of models.

“The Japanese currently weight their JMA model heavily, and it maintains a weak La Niña through mid-winter,” Tony Barnston, an El Niño (and La Niña) expert at the International Research Institute for Climate and Society, said.

This is to say nothing of the atmospheric side of La Niña, which each agency also views differently. L’Heureux also said that other meteorological agencies around the world have even more varied views on what defines La Niña. In Peru, for example, they monitor an area of the Pacific closer to the Peruvian coast because temperatures can drive impacts over the region, according to L’Heureux.

This might have shades of 2014 when El Niño kinda, sorta maybe arrived in September that year and lingered into 2015 before blowing up into one of the strongest El Niños on record last winter. If there’s one thing the three agencies agree on, however, it’s that this La Niña is unlikely to follow a similar pattern.

In the absence of La Niña, the entire U.S. is likely to endure an extended stretch of warm weather for the next three months. In comparison, La Niña usually creates cool conditions in parts of the U.S., notably the Northwest.

On a planetary scale, the heat is likely to march on too, though it’s unlikely to maintain its recent record-setting clip through the fall and winter. Some scientists have predicted a slight respite from the planetary heat in 2017 even without the influence of La Niña. Given that the world is hanging out right at the edge of the 1.5 degrees C threshold, that’s a small consolation, though.