When German chemist Justus von Liebig demonstrated in 1847 that the major nutrients that plants removed from the soil could be applied in mineral form, he set the stage for the development of the fertilizer industry and a huge jump in world food production a century later. Growth in food production during the nineteenth century came primarily from expanding cultivated area. It was not until the mid-twentieth century, when land limitations emerged and raising yields became essential, that fertilizer use began to rise.

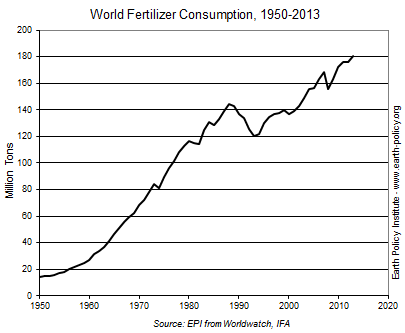

The growth in the world fertilizer industry after World War II was spectacular. Between 1950 and 1988, fertilizer use climbed from 14 million to 144 million tons. This period of remarkable worldwide growth came to an end when fertilizer use in the former Soviet Union fell precipitously after heavy subsidies were removed in 1988 and fertilizer prices there moved to world market levels. After 1990, the breakup of the Soviet Union and the effort of its former states to convert to market economies led to a severe economic depression in these transition economies. The combined effect of these shifts was a four-fifths drop in fertilizer use in the former Soviet Union between 1988 and 1995. After 1995 the decline bottomed out, and increases in other countries, particularly China and India, restored growth in world fertilizer use.

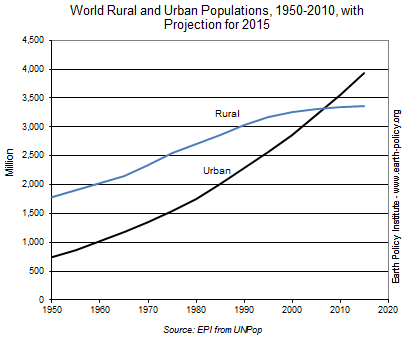

As the world economy evolved from being largely rural to being highly urbanized, the natural nutrient cycle was disrupted. In traditional rural societies, food is consumed locally, and human and animal waste is returned to the land, completing the nutrient cycle. But in highly urbanized societies, where food is consumed far from where it is produced, using fertilizer to replace the lost nutrients is the only practical way to maintain land productivity. It thus comes as no surprise that the growth in fertilizer use closely tracks the growth in urbanization, with much of it concentrated in the last 60 years.

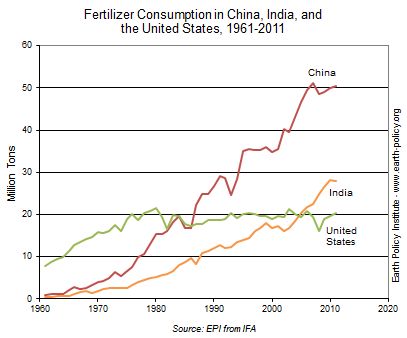

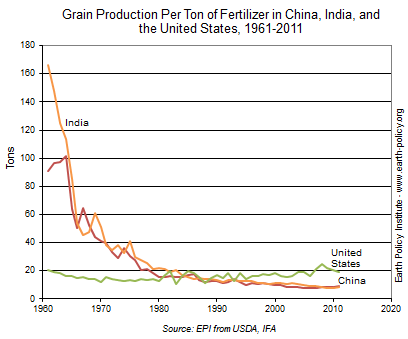

The big three grain producers—China, India, and the United States—account for more than half of world fertilizer consumption. In the United States, the growth in fertilizer use came to an end in 1980. China’s fertilizer use climbed rapidly in recent decades but has leveled off since 2007. In contrast, India’s fertilizer consumption is still on the rise, growing 5 percent annually. While China uses 50 million tons of fertilizer a year and India uses 28 million tons, the United States uses only 20 million tons. (See data.)

Given that China uses 2.5 times more fertilizer than the United States and that the two countries’ average annual grain output totals are similar—450 million tons in China compared to 400 million tons in the United States—the grain produced per ton of fertilizer in the United States is roughly twice that in China.

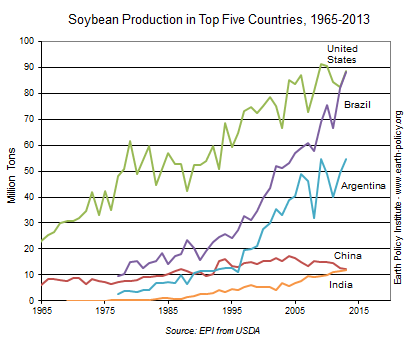

This is partly because American farmers are much more precise in matching application with need, but also partly because the United States is the world’s largest soybean producer. (Brazil’s soy production has recently skyrocketed, bringing it into contention with the United States.) The soybean, being a legume, fixes nitrogen in the soil that can be used by subsequent crops. U.S. farmers regularly plant corn and soybeans in a two-year rotation, thus reducing the amount of nitrogen fertilizer that has to be applied for the corn.

Despite this U.S. advantage in fertilizer use efficiency over China, over-application poses serious pollution problems in both countries. Fertilizer runoff from the U.S. Corn Belt, for example, contributes heavily to an annual oxygen-starved “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico—an area where sea life cannot exist, which in some years grows to the size of New Jersey. Research suggests that U.S. and Chinese farmers could use substantially less fertilizer and maintain or even increase productivity.

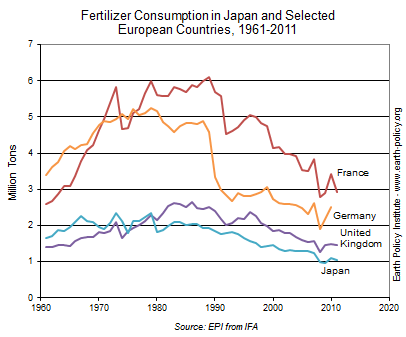

In many other agriculturally advanced economies, fertilizer use has actually fallen in recent decades. France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, which together account for over one third of the European wheat harvest, have maintained high production levels despite significant declines in fertilizer use. Farmers in France and Germany now use half as much fertilizer as they did in the 1980s, while U.K. fertilizer use has dropped by 40 percent. And in Japan, 56 percent less fertilizer is now used than in the peak year of 1973.

There are still some countries with a large potential for expanding fertilizer use. But in the many countries that have effectively removed nutrient constraints on crop yields, applying more fertilizer has little effect on yields. For the world as a whole, the era of rapidly growing fertilizer use is now history.

For further reading on the global food situation, see Full Planet, Empty Plates: The New Geopolitics of Food Scarcity, by Lester R. Brown (W.W. Norton: October 2012). Supporting data sets and PowerPoint presentations are online at www.earth-policy.org/books/fpep.