Forget the feds — we’ll make our own

deals.

The Oakland airport seems perfectly situated. Unlike many urban airports, which require an expensive taxi trip or hour-long train ride to reach the city where you thought you’d just arrived, downtown lies mere minutes away. Such convenience is possible because the runways sit on a former wetland at the edge of San Francisco Bay. But this prime location could prove costly.

We’re all intimately familiar with the basic global-warming scenario by now: greenhouse gases are warming the atmosphere, polar ice caps are melting, sea levels are rising — and coastal cities like Oakland could lose their shorelines. If global temperatures rise 4 degrees Fahrenheit by next century, a relatively conservative prediction, Oakland’s runways flood. And that’s just the start of the city’s potential problems: rising seas could cause billions of dollars in property damage, fill groundwater aquifers with salt water, and jeopardize wetland ecosystems.

City officials are not sitting idly by waiting to see if or when such things could happen. This spring, Oakland became the second U.S. municipality to join the Chicago Climate Exchange (CCX) — North America’s first and only voluntary, but legally binding, emissions-trading market.

Since trading began in 2003, CCX has grown to include 90 participants. Its members include private companies — Ford Motor Co., IBM, and Motorola, Inc., to name a few — as well as universities, nongovernmental organizations, and the city whose name it bears.

While critics say its voluntary nature and limited goals don’t amount to much, members contend it’s a refreshing way to get things done in the absence of federal regulation. Oakland’s move “is a statement that says everybody has to come to the plate and do something about this,” says the city’s vice mayor, Jane Brunner, who led the effort to join CCX and hopes it will inspire others to follow. “It’s time for the United States to take this issue on.”

If You Gild It, They Will Come

The exchange was created by Richard Sandor, who serves as its chair and CEO. A former chief economist with the Chicago Board of Trade — where he became known as the “father of financial futures” — Sandor was named one of Time magazine’s “Heroes for the Planet” in 2002 for helping found CCX.

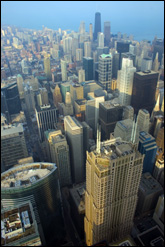

Will the Windy City change the

world?

The Brooklyn native professes a strong belief in the power and salvation of self-regulation. Even if the hammer of government isn’t coming down, he says, the private sector can set standards first.

“Is [the Chicago Climate Exchange] radical?” Sandor asked an audience at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco this spring. “Yeah, it is, but it isn’t … the New York Stock Exchange started regulating companies in capital markets 150-odd years before the [Securities and Exchange Commission] was created.”

This “radical” multi-sector commodities market is based on the relatively straightforward cap-and-trade concept. There’s the cap: an emissions limit imposed on all participants. And there’s the trade: anyone who exceeds the cap can buy credits from those under the cap, in order to remain in compliance. Through this system, the overall level of emissions is collectively lowered. (Cap-and-trade systems have been used for years by the U.S. EPA to help combat pollution, and one was recently approved by the agency — to the consternation of many, including a coalition of states filing suit — as a way of dealing with mercury.)

During the pilot phase, which lasts through 2006, each CCX participant must agree to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions 1 percent per year, using their average output from 1998 to 2001 as a baseline. (These aims were established by a consensus of charter members, and Sandor says CCX will update its post-2006 objectives this summer.) Members must monitor their own progress and, accordingly, their need to buy or sell credits; all reports are externally audited.

The 1 percent annual reduction isn’t overly impressive to some observers. “The companies might do that without even trying, so there’s not a lot at stake financially,” says Michelle Manion, a senior analyst with the Union of Concerned Scientists, who calls the goals “insignificant.” Manion says UCS declined an invitation to join CCX, because it was already self-imposing more aggressive guidelines.

Manion’s argument has some merit. In Oakland, for example, Vice Mayor Brunner didn’t bat an eye when asked if the city could meet the 1 percent goal. She says they would’ve met the goal easily, with or without the motivation of CCX. But Scott Wentworth, an engineer with the city’s energy-reduction program, says CCX adds a punch: “What gets measured gets done.”

Indeed, in 2003, the only year for which data tabulations are complete, CCX blew past the initial goal, with members managing to cut overall emissions by 9 percent. That’s nearly 20 million metric tons of carbon dioxide — the equivalent of Norway cutting its emissions by a third.

I’ll Trade Ya

CCX participants trade units called Carbon Financial Instruments, or CFIs, that are equal to 100 metric tons of carbon dioxide. Prices fluctuate depending on the number of buyers and sellers; at the time of this writing, the trading price was $1-$1.50 per metric ton. So, as an example: Ford Motor Company’s baseline is just over 2 million metric tons of carbon. If Ford had emitted, say, 10 percent more in 2003, it would have cost the company about $300,000.

That’s chump change for a company like Ford — and that, critics say, is a problem. “The [trading] price is not high enough to have an impact on the way people think about carbon dioxide,” says economist Geoff Heal of the Columbia Business School. In other words, the penalty for going over the cap isn’t harsh. Right now, there are also more sellers than buyers. That’s good environmental news — more people come in under the cap than over it — but bad news if you’re trying to create a vibrant market.

Across the pond, by contrast, where Kyoto-bound countries are also trading emissions, the European Union’s exchange is much stronger, with more than 12,000 industrial plants on board. This spring, a unit of carbon in the E.U.’s “Emission Trading Scheme” was worth about $18. So, using the same example, if Ford were a Swedish company that had polluted 10 percent more than its baseline, it would cost $3.6 million to balance out: a tougher pill to swallow. (As it happens, Ford cut its emissions in 2003 by nearly 23 percent.)

At present, a company or organization can’t make much money by being under the cap, either. For example, Amtrak beat its emission goal by 26,600 metric tons in 2003. With current prices for carbon credits, that would net the company about $40,000.

While it may not sound like much, Sandor has faith in the long-term payoff. Ultimately, he says, being a good environmental steward does equate to money in the bank. In the meantime, he and participants say, there are reasons to join beyond immediate financial gain.

The More Things Exchange …

Outside observers aren’t so sure. “I believe that [CCX] is a helpful institution, but the absence of regulatory action by the federal government greatly reduces the number of parties that would be interested, and motivated to participate,” says W. Michael Hanemann, professor of environmental economics at the University of California-Berkeley. “Why would you spend money buying an emissions reduction credit from somebody when you’re not under a compulsion to reduce emissions?”

“This is a good practice ground, but it’s certainly not a substitute [for federal regulation],” adds Manion of UCS. “Voluntary programs are never going to be a substitute for strong mandatory reductions that have to be imposed by the government. There’s just no way around that.”

But Sandor is quick to point out the “first-mover” advantage: companies that have already started monitoring carbon emissions will have a competitive edge, a head start for the day when regulation does come.

“It just makes sense to learn about [carbon monitoring] and get good at it,” agrees Dorothy Schnure of Vermont-based Green Mountain Power Co. Schnure says GMP joined CCX because, in addition to fitting with the company’s values, the market is good preparation in a world moving toward mandatory monitoring.

The Bush administration may not be crusading against global warming, but across the country, at least 150 cities and counties are implementing local climate-action plans. And state governments are also stepping in to fill the void, from the regional greenhouse-gas initiative created by nine states in the Northeast to California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger’s (R) recent announcement of that state’s plans for cuts. If regional and local standards take off, says economist Neal, “the Chicago Climate Exchange would acquire a new degree of relevance.”

Sandor, for one, relishes the market’s pioneering role. Long before the government funded a massive project to put a man on the moon, he points out, there was a 12-second flight in North Carolina. “It’s like the Wright brothers,” he says. “We want to prove that it can be done.”