In an arm-wrestling contest, you’d probably pick Paul Bunyan over John Lawlis. Bunyan, after all, wielded his mighty ax with mythic strength and endurance, leveling the great forests of the upper Midwest. John Lawlis merely works the phones, selling vacation lots in what’s left of these woods. “I think Paul would definitely win,” laughs Lawlis.

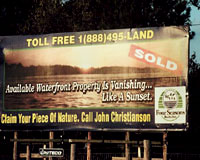

Sign of the times?

Photo: Robert Korth, UWEX.

But it is Lawlis and his fellow realtors who may ultimately prove the death knell to the Great North Woods. “Business is fantastic,” he confided to me. Maybe too good? “We’re having a lot harder time finding anything to develop,” he says. “There’s not much left.”

Not that Lawlis sees himself as a great despoiler of nature — in fact, he considers himself a conservationist. He’s chair of his local Ducks Unlimited chapter, and he recently changed companies, in part because his new employer shows a little more respect for Mother Nature. When people come to him with outlandish schemes to put roads and houses on wetlands, he says no thanks. “There are a lot of things we won’t do.”

But, Lawlis says, “Unfortunately, somebody has to develop it, because it’s inevitable.”

Land o’ lakes.

Photo: Robert Korth, UWEX.

In 1996, Wisconsin’s Department of Natural Resources (DNR) reported that in the previous 30 years some two-thirds of Wisconsin’s pristine lakes 10 acres and larger had been developed, while housing density on private shore lands doubled. The department predicted that all undeveloped lakes — the state has 12,400 lakes in total — not owned by the public would be subdivided and conquered inside of 20 years. “[T]here are just too many of us longing to find that last special lake,” the DNR concluded.

Though Michigan and Minnesota — also well endowed in the lakefront property sweepstakes sponsored by the last Ice Age — don’t keep comparable statistics, they face similar problems. Some Fridays it seems like every car in the upper Midwest is bolting for some “secret” North Woods Shangri-la. A tsunami of baby boomers is approaching retirement, with one hand in the till of a high-octane economy while their 401k’s blush under the beneficence of an epic bull market. To add obscenity to opulence, some of the boomers are even coming into inheritances. Suddenly the dream of retiring to a cabin on a northern lake seems achievable, even modest.

Modest, that is, if your definition of cabin is a 3,000-square-foot home with a bathroom spa, a kitchen bedecked in Italian marble, and a home theatre.

Little Houses in the Big Woods

A historical marker in front of the courthouse in Oneida County, Wisc., commemorates the nation’s first rural zoning ordinance, adopted May 16, 1933. Strapped by the Depression, “the Oneida County board of supervisors resolved the costs of transporting school children and the construction and maintenance of new roads by adopting a zoning ordinance prohibiting settlement in remote areas,” the sign explains.

Those were the good old days.

A little “cabin” by the water.

Photo: Robert Korth, UWEX.

Steve Osterman, the zoning administrator for Oneida County, leads the understaffed, overworked office charged with handling the area’s current land rush. The county has 54,000 parcels of land, he explains, about half of them on water. Between 1994 and 1996, 10 percent — more than 5,000 parcels — changed hands each year. “And when you turn over property, generally it’s to improve it or develop it,” he says.

Of course, improvement is in the eye of the beholder. For many owners of lakefront property, it means not just constructing large domiciles but also importing exotic species. A duck-on-a-stick, with windmill legs; a 10-point buck posing as a weather vane; technicolor pinwheel flowers; cut-out bear, deer, mushrooms, and tulips; a family of loon decoys; a large waterfowl of indeterminate species, color, and artistic origin. Talk about biodiversity. This menagerie — and more — inhabits a mere three lots on the aptly named Lost Lake.

Problem is, these colorful creatures are encroaching on the shore-land zone where Mother Nature crafts some of her gooiest confections. Biologists define the zone as running from about 500 feet inland out into the lake to a depth of some seven feet. Here trees topple into the water and aquatic plants colonize the shallows. The prevailing winds often drive debris against the shore, which decays into a spongy mat. It makes a lousy beach, but it’s a delightful place if you’re a young salamander stud on the prowl.

Unless you have to share bunks with a pink flamingo. This is not about aesthetics; nature seems oblivious to kitsch. But a single pound of phosphorous lawn fertilizer can spawn 500 pounds of plant growth in the lake. As for the link between water quality and septic failure, let’s not go there.

One in 10 of the undeveloped or sparsely developed lakes in Wisconsin harbor threatened or endangered species. And 80 percent of these species spend part or all of their life cycle in the threatened shore-land zone.

Green frogs have got the blues.

Even common species such as the green frog — the loose banjo string in the summer’s amphibian chorus — are in decline. It’s not very complicated: As shoreline dwelling density increases, green frogs decrease. “They like a lot of fallen debris and stuff to hide in. Not surprisingly, as shoreline is developed and put into lawn, the amount of available habitat declines,” says Mike Meyer, a wildlife biologist with the DNR.

More disturbing, when Meyer matched the state’s minimal shore-land zoning requirements to his green frog findings, he concluded that if every lake were developed to its legal limit, the green frog would effectively be eliminated from Wisconsin lakes. Lake protections are being tightened, but the likeness of Kermit on swimsuits and diapers may still wind up more abundant than the native green frog.

Are we headed for the silence of the loons?

Photo: Mike Meyer.

Still uncertain is the impact of development on loons, whose loopy, ululating calls embody the mystique of the North. While loons can coexist with development, the common loon is currently a threatened species on Michigan lakes. Its food sources are degraded by poor water quality, its potential nest sites are eliminated by shore-land development, and boat traffic can cause the birds to desert their nests.

Land’s End

How can we avoid the slide from On Golden Pond to the golden arches? The problem stretches from the Adirondacks to the Outer Banks, from Cape Cod to U.S. 101.

For goodness lakes!

Photo: Sherry Bosse.

“Development’s going virtually everywhere now,” says Ed McMahon, director of land-use programs for the Conservation Fund. And rural communities are particularly vulnerable because they are often opposed to regulation. However, he’s heartened by what he’s seeing in a number of small mountain communities across the West that have realized land-use regulation is not an enemy o

f progress but a tool with which to preserve the land they love. “Change is inevitable, but the destruction of community character is not,” says McMahon.

“It’s not hard to understand why people love the lakes and so want to build a lake home,” says Dave Cieslewicz, executive director of 1000 Friends of Wisconsin. He believes the challenge now facing enviros is to promote city living. If people love natural areas, they need to leave them alone. “The whole thrust of the environmental movement has missed that point,” he says.

And if it fails to catch on, there is always the revenge of the locals. McMahon tells a story about Gatlinburg, Tenn., which “used to be a quaint little town on the edge of the Smoky Mountains National Park. Now it’s the bungee-jumping, water-slide capital of America.”

One day a ranger friend of his, while walking downtown, was flagged down by a tourist with a dire query: “I’m only going to be here for two days. Should I see the outlet malls or the national park?”

He sent her to the malls.