The highlands of Papua New Guinea cradle some of the most remote places in the world, and are home to an astounding diversity of languages, cultures, and plant and animal life — including the Asian Pacific’s largest intact stand of tropical forest.

Anne Kajir.

Photo: Goldman Environmental Prize.

Since the 1980s, industrial logging has torn through the forests of this island nation. The government of Papua New Guinea has a cozy relationship with the timber industry, particularly with Malaysian logging companies, and illegal logging is rampant. Though traditional communities are guaranteed land rights under the national constitution, these rights are often ignored, and forest landowners report extreme intimidation and abuse at the hands of timber companies.

Attorney Anne Kajir has spent most of her adult life fighting for traditional landowners. The CEO of the Environmental Law Center in the capital city of Port Moresby, Kajir has used court cases and legal education work to force the logging industry to pay damages to some indigenous landowners. Though she has been physically attacked and robbed in retaliation, she has persisted with her campaign, and is currently the lead attorney in a Supreme Court case against a multinational timber conglomerate.

Despite victories by Kajir and her allies, the power of the timber industry is growing. Last year, a new national forestry bill stripped away landowner-consent requirements for timber permits. It also removed a seat for environmental interests on Papua New Guinea’s National Forest Board, replacing it with a seat for the timber industry. “We’ve gone back to square one,” says Kajir.

Kajir, 32, was awarded one of six 2006 Goldman Environmental Prizes at a ceremony in San Francisco on April 24. She spoke to Grist from San Francisco.

Tell me how illegal logging is affecting the forests and people of Papua New Guinea.

Illegal logging is happening all over the country, and unfortunately, 40 percent of the forest in Papua New Guinea is already gone. That’s frightening enough, but it’s going from bad to worse. Basically the companies that are logging in Papua New Guinea do not comply with the laws that we have in place, and they disrespect the landowners. The government is clearly supporting logging, and every single day there are permits being granted illegally, and new projects starting. There’s simply no control over logging.

Landowners are usually the ones most affected, simply because most of their land is destroyed. They have to walk longer distances to fetch clean water, and women have to go deeper into the forest to look for food. In many of these areas, there is no proper infrastructure being built — no proper school, no proper hospital.

How did you begin defending the rights of local landowners?

Traditional landowners in a logged area in the country’s Western Province.

Photo: Greenpeace-Schellema.

I became involved as a volunteer for a public-interest environmental law organization, and I used to visit a lot of the remote communities and conduct legal awareness trainings. One time, a woman approached me and asked if I could help her. She could not speak English, or pidgin, but she asked me through a translator if I would follow her. So I followed her, and she showed me a piece of land that had red ribbons tied around it in a square. She said, “You see this place? This is my sacred land. This is where I believe my ancestors came from.” It was like the aftermath of a volcano. Things were buried underground, trees were buried under soil, everything was mud and — yuck. It had been completely devastated. They are supposed to be doing selective logging, but it’s just mass destruction.

So this woman said to me, “You stop the logging. I don’t want this to happen in any other place, on any other part of my land.” I said, “You know, I cannot promise you that I’ll stop the logging, but I’ll try.” And that’s where I’ve been ever since.

What do you consider your most effective strategies?

You have to educate the people, to get them to know their rights and act upon them. In Papua New Guinea, we’ve lost the battle already — you can’t go to a government department and argue your case, because you don’t get anywhere. The only way we can get anything done is to push through the court system.

What can people in industrialized countries who care about this issue do to help your cause?

The consumers need to watch what they’re buying. If they’re buying timber products, they need to make sure the timber isn’t illegal — they need to make sure it’s not coming from places like Papua New Guinea, where most of it is illegal.

Do you see signs of hope?

The landowners are not as illiterate as they were before. More people are being educated about what is right, and a lot of people are now speaking up. So many landowners are going to court out of frustration, because they have no other means of settling their issues.

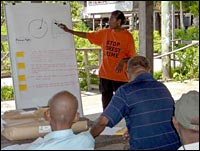

Kajir leads a community workshop.

Photo: Will Parrinello.

What do you consider your greatest victories?

Well, obviously, the Goldman is one of them. I used to think that it was only a small world that I was working in, but to receive this award is quite significant — now the whole world knows about our efforts. I hope the Papua New Guinea government can see this as a sign that we need to get things right with the environment back home.

How do you plan to use the money?

I’d like to support the work that we do. And of course [laughs], I’d like to buy a house, and go sailing.

What gives you the energy, and the strength, to keep going?

Seeing people satisfied at the end of the day, I suppose. Seeing the light in the landowners’ eyes when they say, “Oh, we didn’t know that we had [these rights], and now we know.” They know they’ve got somebody to help them, and you know you’re there because they’ve asked you. It’s a special relationship that you have with these people.

I just like seeing people happy, you know? So it basically gives me the kicks every time the landowners smile and say, “Thank you.”