Dear Umbra,

I’ve been hearing about rising ocean temperatures more and more. My question is, what are the criteria for measuring the temperature of the ocean? Wouldn’t probe location, probe depth, water depth, prevailing current, time of day, and ambient temperature all potentially affect the result? Have the criteria remained constant for the recorded history?

Douglas

Seattle, Wash.

Dearest Douglas,

I became riveted with the present and its modern, bizarro ocean measurement technique while finding the answer to your question about the past — so let’s quickly dispense with some background.

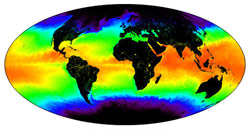

A current affair.

Image: NASA.

“Warming of the World Ocean,” by Levitus et al., seems to be the leading document referenced by the cognoscenti, including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Levitus et al. assessed 50 years’ worth of data. My non-scientist understanding of how the authors dealt with (as you accurately describe) wide variations therein is that they looked for consistency within oceans, within depths, within measurement techniques. I believe there are more than 5 million worldwide data points from the 1950s onward that have been run through insane computer programs designed to bunch some data as useful and reject others as too odd to be real. Basically, given that much data, Science will find a consistent way to compile it and make it reliable. So although it was not consistent for recorded history, they have found a consistent way to examine it.

Older temperature measurements came from researchers and sailors gathering information at latitudes and depths around the world. We have records of ocean surface temperatures from the late 1970s onwards from satellite photography. Coral growth also indicates changing temperatures — to the discerning scientist, if not the snorkeler.

Enough about the past, because since the 1990s temperature change in the North Pacific has been measured with sound. Check it out! The ocean’s surface is heated by the sun and changes temperature relatively often compared to its depths, where the sun don’t shine and temperature is constant and cold. Neither the top nor the bottom shows us too much in a decade, but in between is the “thermocline,” and here Science frolics.

Basically, sound’s velocity through water is a strong function of the temperature of the water. There is a sort of channel in the thermocline called a waveguide — or the Sound Frequency and Ranging channel — down at about 750 to 1,000 meters in the tropics and up around 200 meters at the poles. Very low-frequency sound produced in the SOFAR channel will stay in the channel as it travels through the ocean, because the temperature and pressure differentials above and below the waveguide depth will continually refract the sound back into the waveguide. Got that?

So the Acoustic Thermometry of Ocean Climate and North Pacific Acoustic Laboratory experiments produce sound at SOFAR depth at one location, and listen for the sound at multiple other locations. Scientists know when the sound was produced, and how far the receivers are from the speaker, and from this information can learn about the changing temperature of water in the SOFAR channel. They’ve checked the data against other measurement techniques, and checked to be sure they aren’t deafening whales, and this technique seems like a great way for us to keep track of changing ocean temperatures.

OK, I’m using “us” kind of loosely here. I’m sure I’ve somewhat macerated Science as usual, so you’ll want to look through the provided links if my brief summary does not suffice. I will say I feel we’re in good hands, and who knew about this sonar stuff? The mind boggles.

Wavily,

Umbra