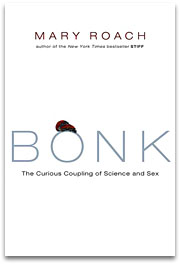

Ah, sex. Source of carnal bliss, domestic harmony, cute infants … and global population problems. (Oh, environmentalists are such killjoys.) Overpopulation aside for the moment, sex is fundamental to humanity, and to the rest of the natural world — and besides, it’s a dang fascinating subject, as Mary Roach found out while researching her new book Bonk: The Curious Coupling of Science and Sex.

Mary Roach.

Photo: David Paul Morris

To produce her latest work, Roach delved into the quirky and occasionally sordid history of human sexual research, following the fearless scientists who devote their lives to figuring out exactly how the deed gets done. In the process, she learned that rats wearing polyester underpants have lower sperm counts, that the scent of Good & Plenty could make you irresistible to potential partners, and that participating in a sex study is just about the least sexy thing you can do. Grist caught up with her recently to find out more.

Are these scientists really that different from scientists who are, say, obsessed with ants, or orchids, or other aspects of the natural world?

I don’t think so. Someone who gets interested in sex, that’s actually much more understandable, because sex is such an endlessly interesting topic — it makes perfect sense that someone would want to study it. On the other side, these scientists have had to deal with the possible misunderstanding of peers and their families, which was more of an issue in the ’40s and ’50s than it is today.

What are some of the things we’ve gained from these studies? I mean, how has science contributed to our sex lives?

In [late 19th century sex researcher] Robert Latou Dickinson’s archives, he talks about some of the people who came to him with a profound ignorance about sex. There was a couple who thought they’d had sex when the guy hadn’t gone further than the outer labia — they said, ‘Well, we’re having trouble getting pregnant,’ and it took someone like Dickinson to say, ‘Well, what are you doing in bed?’ In the Victorian era, there was just no imagery to come by, no sources of information, nobody talking about it. So at a very basic level, getting people to feel comfortable speaking about it was a pretty valuable thing.

You and your husband participated in one of these studies — I won’t ask you to recount the details, but did it change your feelings about the scientific study of sex?

What it did was address a certain curiosity that I had when I read [the work of sex researchers] Masters and Johnson. I thought, ‘How the hell could anyone do this in front of researchers?’ And what better way to find out than to do it yourself?

Like most things you cannot imagine, it’s less onerous and simpler than you anticipated — there’s this fear and apprehension because it’s such an unknown, you can’t picture the scene, can’t imagine what anyone will say — and then when you get there, it’s like any other medical procedure. I mean, I was taking notes during it.

You’re kidding! You were not!

I was. And [my husband] Ed was just like, ‘Dear God, let me get through this.’ It was as though it wasn’t sex. If it had been a study of female orgasm, I wouldn’t have been able to help them out.

So, science can tell us a lot about sex. But what can’t science tell us about sex?

Bonk, by Mary Roach.

Science is not very good at factoring emotion into sex. Someone’s emotional state is a huge factor in what sex is like, and that’s really hard to study in a lab. There was a Masters and Johnson study from the ’70s that compared committed gay and straight couples and couples who had been assigned partners — that touched on qualitative issues, the differences between efficient sex and really great sex. Even then, if you were to try and pin down how being in love affects arousal and orgasm, how does passion affect it — how do you begin to define those things, how do you know that the [people who say] they’re in love are in love? Trying to study love in the lab doesn’t work very well.

OK, so you have to tell me a little bit about the rats in Egypt and their polyester pants.

[Egyptian sex researcher] Dr. Ahmed Shafik was a fairly extraordinary guy, and I was fascinated by his work. I came across his rats-in-underpants study before I went to see him, so when we met I brought it up, and I was kind of exclaiming with glee that they had made underpants for rats. And he said ‘Yes, yes, we did that,’ and I realized that he didn’t think it was all that strange. I was going to ask to see the underpants, but then I thought that would make me seem like I was trivializing his work. So I didn’t push to see the underpants, and now I regret that. Maybe he would have given me a pair. I did a story on sumo wrestlers once, and I meant to go to the store where they sold sumo wrestler underpants. I regret that, too — I would have had the makings of a fine little underwear collection.

When [Shafik] found that the polyester lowered sperm count [in the rats], he actually came up with a polyester scrotal sling that he would have advocated as male birth control. While it might have been effective, it would have been hard to convince a man to wear a scrotal sling that you had to launder separately. It wasn’t a hugely practical notion, but I kind of admired him for looking into it.

So, I need to ask you something on behalf of Grist readers. Grist is an environmental magazine, and environmentalism is not often seen as a very sexy topic. Any advice from science for environmentalists looking to increase their sex appeal?

Well, don’t wear polyester pants, number one. Don’t wear cologne — cologne lowers female vaginal blood flow. You could slather yourself in Good & Plenty, that’s supposed to [have the opposite effect]. Don’t bother smearing synthesized rhesus monkey copulins on your chest, in case you were planning to attempt that. Likewise, Boarmate — the synthesized boar pheromone — it’s hideous. It’s like a musty, intense body odor times a thousand. It’s the most repellent odor. I’m not being very helpful, though.

You’re just finishing up a book tour. What did your readers most want to know from science about sex?

People have been volunteering some things. A guy who’s a sex researcher stood up and asked me if I’d heard about sperm surfing, and I said ‘No, I have not! Please tell me!’ I was so crestfallen that I’d somehow overlooked sperm surfing. It’s something about how sperm navigate the vaginal wall, some kind of surfing they do, which seems kind of incredible to me given that they have no arms and legs, and no surfboard.

Then there was a radiologist who wrote an email to me about this footnote that I had, about a comprehensive review of the world’s literature on things stuck in rectums. He wrote that several different kinds of small, furry rodents — well, that some cases had come to his attention. I wrote back and said, ‘Is there a paper, or do you have an X-ray?’ He said he’d been called in to look at an X-ray where they were trying to figure out if it was a hamster or gerbil. And I said, ‘Who cares? Who gives a shit if it’s a hamster or a gerbil? You just gotta get the thing out!’ He didn’t write back to me.