This story was originally published by Mother Jones and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price resigned on Friday, following revelations that he had taken at least two dozen private and military flights at taxpayer expense since May. But who hasn’t been taking private flights among the members of President Trump’s Cabinet? We now know that Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin, Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Scott Pruitt, and Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke have all flown on noncommercial or government planes rather than commercial ones, collectively racking up hundreds of thousands of dollars in costs to taxpayers. Zinke went so far as to fly on a plane owned by oil and gas executives after giving a motivational speech to Las Vegas’ new National Hockey League team.

For Pruitt, the news comes as he’s found himself battling several other mini-scandals from his short tenure. He’s faced congressional inquiries for having an 18-person, 24-hour security detail, building a nearly $25,000 secure phone booth for himself, and taking frequent trips to his home state of Oklahoma. But the most jarring aspect of his plane controversy is how it looks against the Trump administration’s proposal to cut one-third of the EPA budget.

The Washington Post reported Wednesday that Pruitt has taken at least four trips on chartered and government flights since his confirmation, at a cost of $58,000, according to documents provided to a congressional oversight committee. The EPA has defended Pruitt’s travel by saying the four noncommercial flights were for necessary trips to meet stakeholders around the country and that there were special circumstances that prevented commercial flying.

But what exactly was Pruitt up to on these trips? On one of them, his only public meeting in Oklahoma, he and six staffers took an Interior Department plane from Tulsa to Guymon, a town in Oklahoma’s panhandle, at a cost of $14,400. The trip’s stated purpose was to meet with landowners “whose farms have been affected” by a federal rule making more bodies of water subject to regulation under the Clean Water Act. Pruitt has argued for overturning the rule since before his arrival at the EPA, and he has begun the process of reversing it.

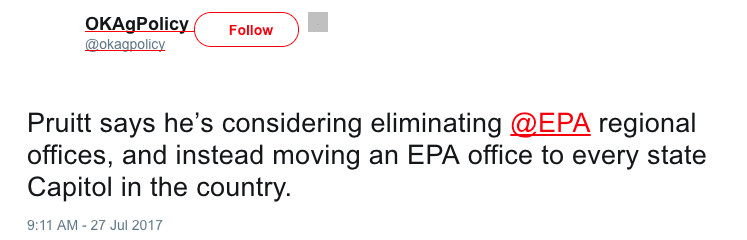

One of the things Pruitt reportedly talked about in his meetings with farmers in late July was closing the EPA’s 10 regional offices and reassigning staff to work in state capitals. According to an affiliate of the Oklahoma Farm Bureau that helped organize the event and was tweeting about his remarks that day, Pruitt floated the idea to an audience of farmers assembled in Guymon.

A screenshot of the tweet provided to Mother Jones. The original tweet appears to have been deleted.

The farm policy publication Agri-Pulse took note of the tweet and requested comment from the EPA at the time. Agency spokesperson Liz Bowman told the publication that Pruitt “believes it is his responsibility to find the best and most efficient way to perform environmental protection” but repeated that there weren’t plans to close any regional offices “in the foreseeable future.”

Politico reported earlier this year that the White House was looking at shutting down two of the EPA’s 10 regional offices in its budget request. A Chicago Sun Times columnist reported that the Chicago EPA office, where 1,000 people work, could be on the chopping block. Though the agency quickly denied the rumors, there were protests not just from EPA staff, but from Democratic and Republican politicians representing areas that would be affected. By June, the idea appeared to be off the table. That month, Pruitt told members of the House Appropriations Committee that he did not intend to close regional offices. He dismissed the reports that he was considering closing the Chicago office as “pure legend,” saying, “It is not something that is under discussion presently.”

The EPA employs roughly 15,000 people, many of whom work across the country in regional offices, carrying out day-to-day environmental oversight and delivering grants to fund state environmental programs. In early May, Democratic senators who sit on the oversight committee for the EPA wrote to Pruitt, “Whether reviewing discharge permits for compliance with Federal pollution standards and state water quality standards, or inspecting facilities to see if they are operating in compliance with their permits, we count on regional staff to provide guidance to state pollution control staff, the public and regulated entities.” Regional staff, for instance, have played a key role in the response to recent hurricanes, analyzing soil and water samples for contamination. It’s unlikely that Pruitt would seek simply to move the EPA’s regional office staffers to state offices. He has already sought to cut more than 1,000 positions from the agency through buyouts, and the closure of regional offices could be an additional pretense to eliminate jobs.

On Thursday, the EPA declined to give Mother Jones more context on Pruitt’s remarks about regional offices that day or why he would be floating the idea well after denying it was under consideration. Instead, EPA spokesperson Jahan Wilcox offered this statement: “Anyone that takes time to read President Trump’s budget will realize that no money is allocated to close down regional EPA offices.”

The president of the EPA employees union, John O’Grady, commented that closing regional offices and moving the regulators into state capital buildings would be “a whole ball of wax” that the administration hasn’t thought through.

“If they do that, I’m going to come out and say quite frankly we’re thrilled that the administration has decided to put U.S. EPA employees at the state office,” he said. “Now we can tell for sure that the states are following federal laws correctly.” He added, “They’re trying to dilute the EPA as a cohesive unit. They’re trying to get rid of us.”