This story was originally published by CityLab and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In financial terms, 2017 was the worst year for natural disasters in American history, costing the country $306 billion. Scientists agree that hurricanes, floods, and fires are now turbo-charged by climate change, which the president and many top Republican leaders still refuse to acknowledge. But even while the federal government fails to address the root of the problem, there are ways to limit the damage from these increasingly frequent events — in property, and, more importantly, in human life.

A new report from the National Institute of Building Sciences finds that for every dollar spent on federal grants aimed at improving disaster resilience, society saves six dollars. This return is higher than previously thought: A 2005 study by NIBS found that each dollar from these grants yielded four dollars in savings.

“A lot of things have happened since 2005,” said NIBS’s Ryan Colker, who contributed to the report. “Katrina, Sandy, and the increasing … frequency of disasters prompted us to look at what has changed.”

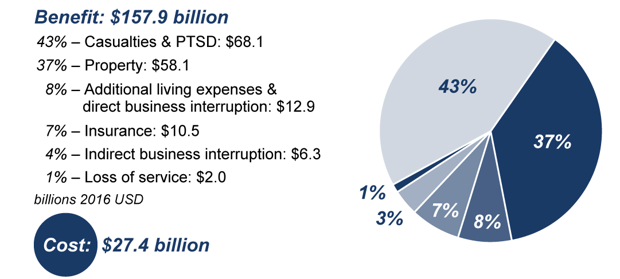

NIBS, a nonprofit group authorized by the U.S. Congress, took into account grants from FEMA, HUD, and the Economic Development Administration, whose staffs collaborated with NIBS to produce the report. $27 billion spent in mitigation grants over the past 23 years has yielded $158 billion in societal savings, they found. Many of the interventions the grants funded were simple, like installing hurricane shutters, replacing flammable roofs, and clearing vegetation close to a structure.

Summary of the savings attributable to federal disaster-mitigation grants (NIBS)

In addition to federal grants, the report also examines the financial benefits of private developers exceeding local building resilience standards. These interventions — such as elevating homes higher than required in flood-prone areas and building structures to be more rigid than required by seismic safety rules — yield four dollars in savings for every dollar spent. Unlocking these benefits is more difficult, however, since they are contingent on the decisions of private builders.

“As we continue to produce information about the benefits of resilience,” Colker said, “I think you can see an increased recognition from builders that people are willing to pay for this. There’s value associated with it.”

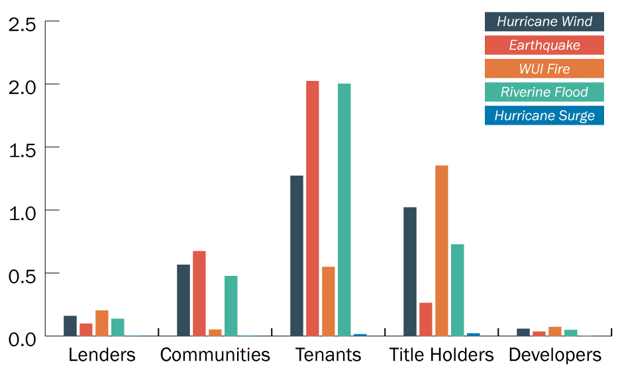

The study finds that developers accrue a small benefit from these long-term investments in disaster mitigation, but not nearly as much as tenants and property owners.

Net benefits to various stakeholders for exceeding local safety requirements in new buildings (NIBS)

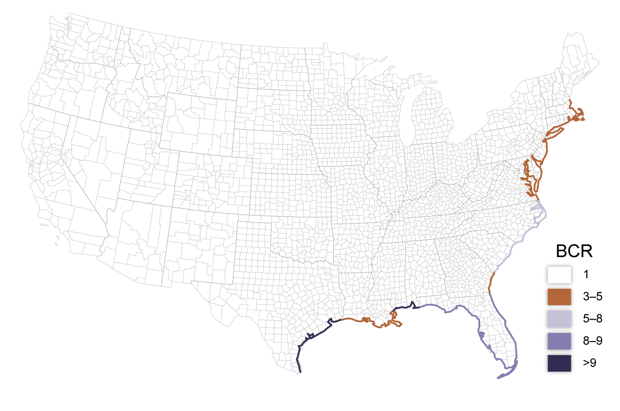

Some regions benefit disproportionately from both federal disaster-mitigation grants and better building practices. Stretches of the Gulf Coast, for instance, see a high benefit-cost ratio (BCR) on dollars spent to elevate buildings above the legally mandated height.

Benefit-cost ratio of raising new buildings above required threshold in coastal areas (NIBS)

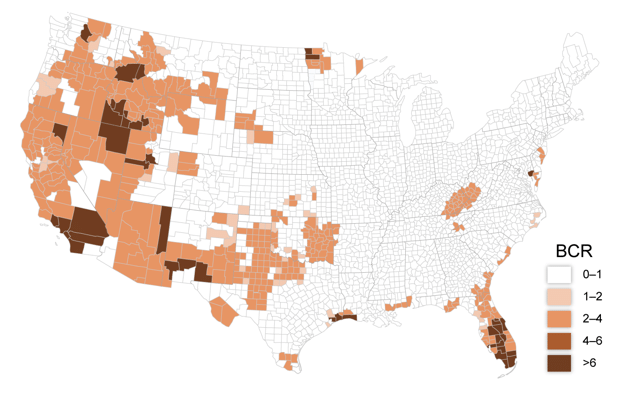

Large swaths of Southern California, Idaho, and (somewhat surprisingly) Florida derive particularly great benefits from investment in fire-mitigation efforts in new construction.

Benefit-cost ratio of implementing various fire safety measures in new buildings (NIBS)

Ironically, the federal grants that this study reveals to be more effective than previously thought are on the chopping block in Trump’s first budget request. Specifically, FEMA’s pre-disaster mitigation grants would be cut in half; HUD’s Community Block Grant Program would be ended, and the EDA would be eliminated.

Meanwhile, FEMA’s Trump-appointed administrator, Brock Long, “is very much interested in increasing investment in mitigation up front,” according to Colker. It will be interesting to see how the administration’s intent to cut city and state grants of all kinds will square with Long’s position, which is now supported by empirical evidence from the NIBS report.

If the president and Congress are unwilling to act on climate change, at least FEMA has a proven strategy for mitigating its effects. That is, of course, if the agency has the money to implement it.