Last May, scientists uncovered a worrying trend — there was a global uptick in the emissions of internationally banned, ozone-depleting pollutants. Now, the mysterious rise has been pinpointed to two provinces in Eastern China.

If you’re thinking: “Wait, what? The ozone layer? Didn’t we fix that way back when?” Well, we started to.

A quick primer: The ozone layer is a part of the stratosphere that protects us from harmful UV light — it’s basically the Earth’s sunscreen. Our long history of worrying about this invisible layer started in the mid-’70s, when studies suggested that human-emitted pollutants like chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) might be depleting it. When an alarmingly thin portion of it was found over Antarctica, people freaked out. News articles warned of significant increases in skin cancer and risks to agriculture. Pretty scary stuff.

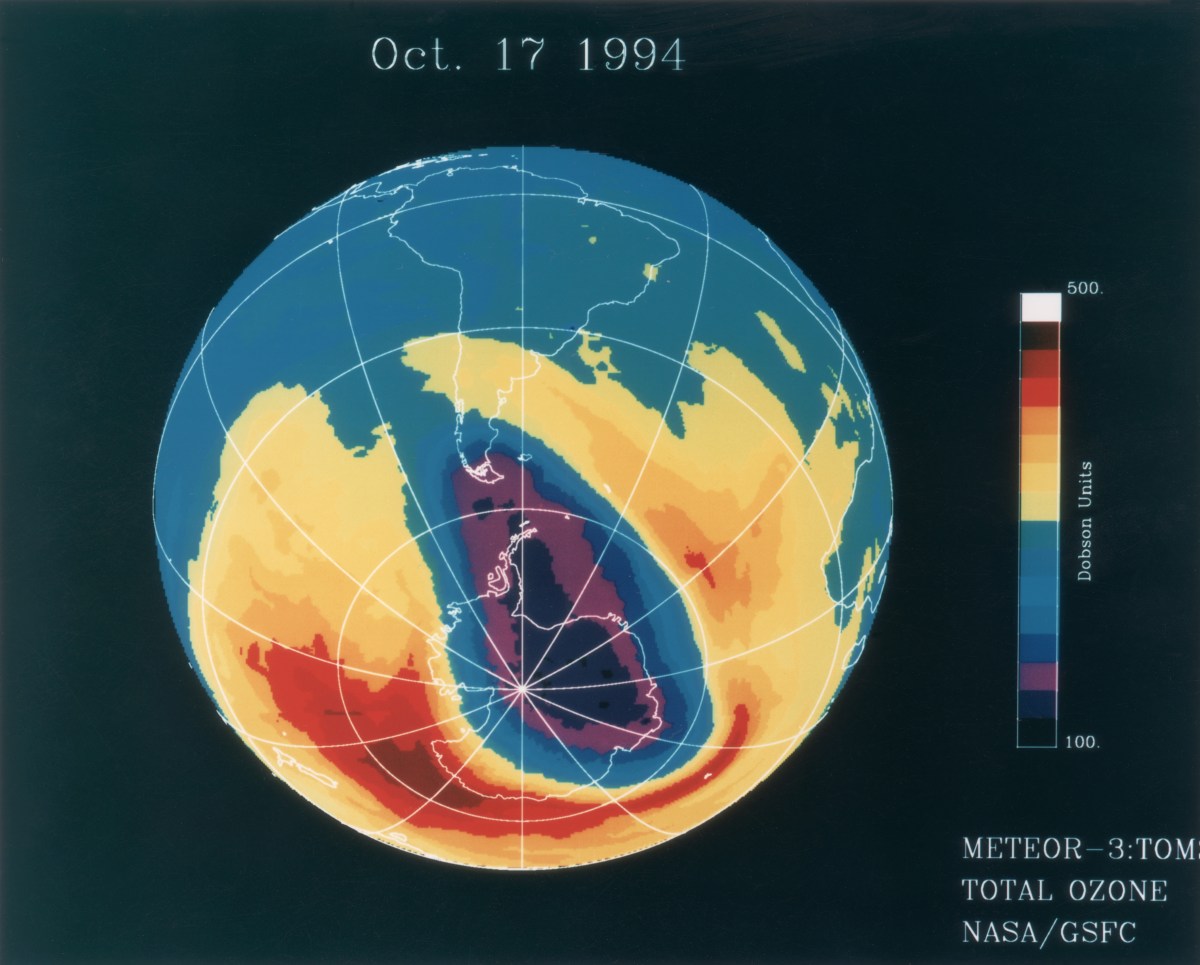

A hole in the ozone layer above the tip of South America, as measured by The Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer (TOMS) on board Russia’s Meteor-3, in 1994. Space Frontiers / Getty Images

The world rallied around the issue and adopted the Montreal Protocol in 1987, which required the phasing out of ozone depleting substances like CFCs by 2010. It was a big win, and soon enough, the ozone layer began to fix itself. Case closed.

That is, until 2018. A study published in Nature last May revealed that the rate of decline of atmospheric CFCs significantly slowed after 2012. The scientists were quite certain that there were new emissions of this banned substance coming from somewhere in East Asia, only, no one could figure out from exactly where.

One year later, a new study, also published in Nature, pinpointed the location of these illegal emissions in Hebei and Shandong, two industrial provinces in northeastern China with notoriously bad air pollution. The provinces manufacture everything from glass, iron, and petrochemicals to food and drink.

Although the new paper did not specify what processes were responsible for this CFC bump, the Environmental Investigation Agency has a pretty good guess. Following the discovery of new CFC emissions in May 2018, the EIA led a ground investigation and found that 18 out of 21 inspected Chinese foam factories in 10 different provinces were using CFC-11 in the production of polyurethane foam.

A material as versatile as plastic with incredible insulation properties, PU is probably all around you right now, keeping your building warm or cool, and cushioning the carpet beneath your feet. Only, PU doesn’t have to be made of CFC-11 — that just happens to be a cheap, readily available option, which is likely why so many Chinese companies appear to be using it.

How could the Chinese government allow the production of such a potent pollutant for over seven years? Dongsheng Zang, an associate professor and director of Asian law at the University of Washington, believes we may never know due to a lack of transparency in Chinese environmental regulation.

“In the past 30 years,” Zang said, “there have been different versions of the Environmental Protection Law, but the mechanism of enforcement has been fairly weak.” He pointed out that NGOs and private citizens are limited in what they can do to push for enforcement.

In recent years, China has been a wildcard when it comes to environmental regulation. While the federal government has been taking huge strides toward renewables, and is planning on creating 13 million clean energy jobs by 2020, local governments have repeatedly put economic needs over environmental ones.

A 2018 study looked at data from almost 300 Chinese cities between 2003 and 2010, and found little evidence that environmental regulations were curbing air pollution. Moreover, the trends they observed supported the “pollution haven” hypothesis — that polluting industries, instead of complying with regulations, will simply move to areas with less stringent regulations.

Recently, China’s economic growth has been the slowest in almost 30 years, and coincidentally, the country has also seen higher pollution levels. While local governments say the temperamental weather is to blame for the smog, some environmentalists suspect that reducing air pollution may be on the backburner until the economy bounces back.

In the case of CFCs, however, Chris Nielsen, executive director of the Harvard-China Project, thinks the federal government may be pressured into directly interfering.

“The stakes for the central government in terms of international reputation are far larger than the modest market these illicit chemicals represent,” Nielsen told Grist via email. “Given there are safe substitutes that are only somewhat more expensive, I suspect the central government is itself very unhappy about this lapse in local enforcement.”