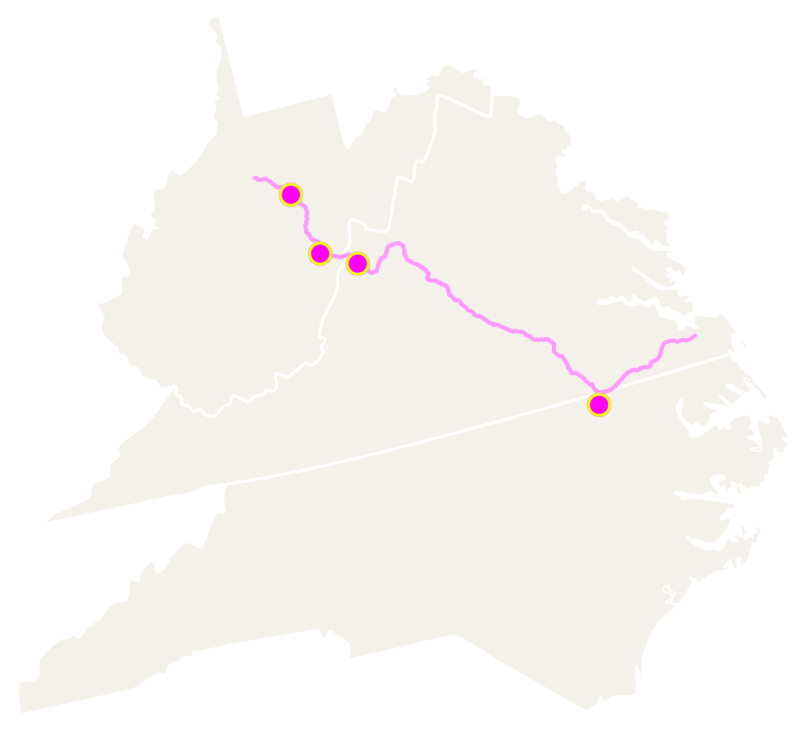

The pink ribbons start in northern West Virginia. Tied to flimsy wooden posts stuck a few inches into the earth, they’re easy to miss as they whip in the crisp, fall wind. Heading south, they dot landscapes for 600 miles, marking the proposed route of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. They pass over cave systems and watersheds, climb up and down densely forested Appalachian slopes. They stamp quiet hollers and hillside family cemeteries. They divide historic African American communities and indigenous land.

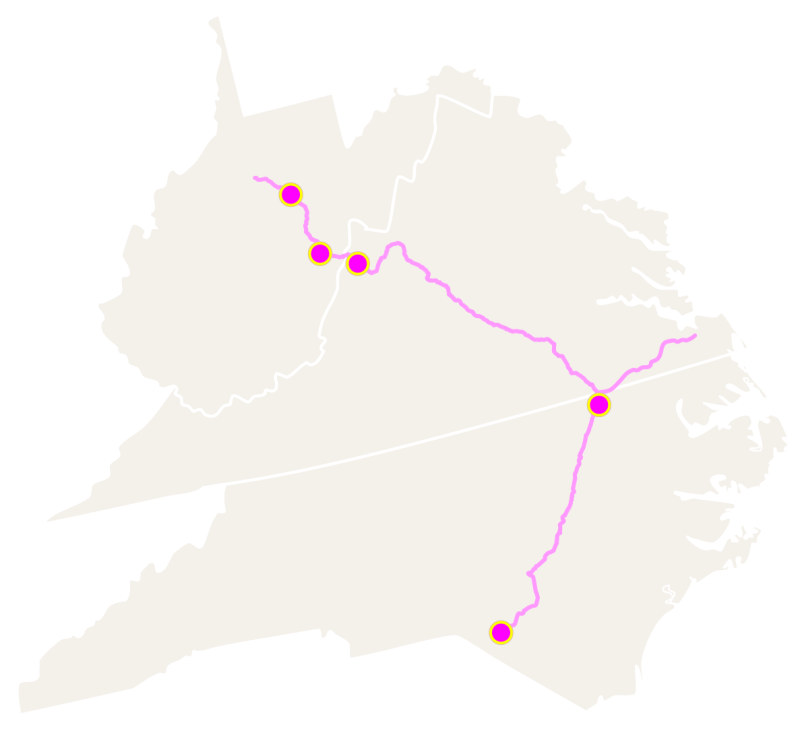

The route stretches from the Marcellus Shale region of West Virginia, through Virginia, to southern North Carolina — though the energy companies behind the pipeline have floated the idea of extending it into South Carolina. If completed, the hundreds of miles of 42- and 36-inch diameter steel would carry 1.5 billion cubic feet of natural gas every day — enough to power 5 million homes daily. Three compressor stations along the route would help transport the gas, and, like much of the pipeline, would be built in lower-income, rural communities, bypassing more affluent property owners.

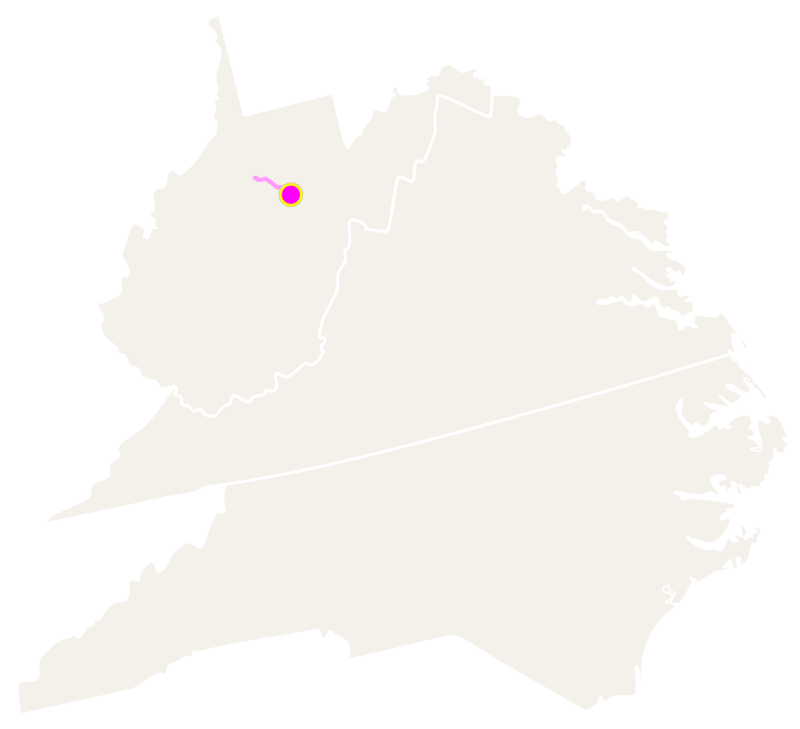

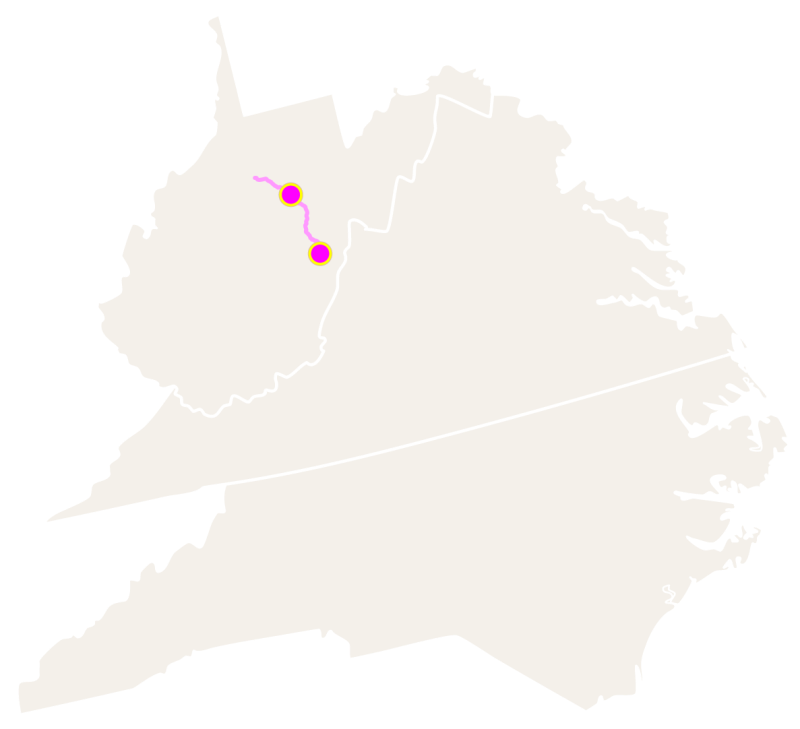

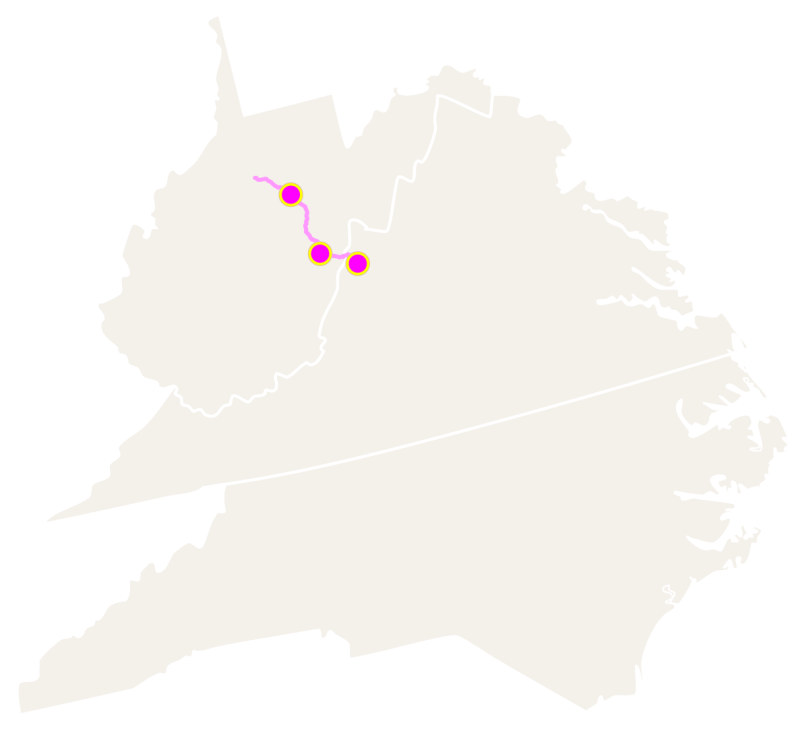

The proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline is slated to run from West Virginia into North Carolina, and is part of a shift in the energy industry away from coal to natural gas. Lyndsey Gilpin

The project is part of a pipeline boom in the United States prompted by the fossil fuel industry’s shift from a fuel source on the decline, coal, to one on the rise, natural gas. Dominion Energy owns the majority share of the project, which was first proposed in 2014. Some of the most powerful utilities in the Southern U.S. — Duke Energy and Southern Company — own the rest. Those utility companies are also the wholesalers that would profit by reselling the gas to their ratepayers. The companies say the project is necessary because they and other utilities serving Virginia and North Carolina need cheaper gas. And they claim it would be an economic boon to the region, estimating that it would provide 17,000 construction jobs and generate $28 million each year total in property taxes for the 25 counties and two cities it will pass through.

But economists, environmentalists, researchers, and many residents in the places the pipeline would pass through say the project’s risks and costs outweigh its potential short-term benefits.

The promise of employment, for example, doesn’t shake out: Most of the pipeline’s construction jobs are highly specialized, so many of the workers have come from out of state. Dominion spokesperson Samantha Norris said that once the pipeline is operational, “a few dozen inspectors and technicians” will be employed to maintain it.

Further, the utility companies seem to be overstating regional demand: In Dominion’s most recent long-term energy plan, most scenarios showed no increase in regional consumption through 2033. Instead, the U.S. is expected to be a leading exporter of natural gas within five years. Some opponents suspect that much of the gas carried by the Atlantic Coast Pipeline would be shipped overseas.

Meanwhile, the project’s environmental threats are stacking up. Scientists warned during its environmental impact assessment that the mountainous terrain the pipeline would run through is unstable in spots. Where construction has begun, there have already been problems with erosion and sedimentation. There are also risks of natural gas leaks and explosions that could endanger nearby communities and contaminate drinking water supplies and wildlife habitats. And the concern over emissions of the potent greenhouse gas methane from natural gas extraction is only growing as global temperatures rise and countries and states work to address climate change.

Tom Clark stands in a flooded construction site holding a hula hoop that is 36 inches in diameter — the width the Atlantic Coast Pipeline is slated to be in North Carolina. Clark has been protesting the project, which would pass near his home in Cumberland County, for years. Lyndsey Gilpin

For years, the Atlantic Coast Pipeline has faced intense scrutiny for receiving expedited approvals from government officials without sufficient oversight. In 2017, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, known as FERC, approved the overall project. The Department of Transportation oversees safety regulations on how interstate pipelines are constructed, tested, and inspected once they’re in the ground, said Carl Weimer, executive director of the Pipeline Safety Trust, a Washington-based organization that advocates for pipeline safety regulations. But populated areas receive the lion’s share of the regulations. Federal rules are more lax in rural areas, he said — and all of the areas the pipeline would pass through are considered rural.

“It’s cheaper to build in rural areas — they don’t have to worry about added regulations when they do that,” Weimer said. “But if there’s a pipe next to your house that blows up, you’re gonna be just as dead as someone in a populated area.”

Originally scheduled to be in service this year, the project is tangled up in legal battles, and construction is less than 6 percent complete, in terms of miles of pipe in the ground. Despite the setbacks, Dominion remains confident that the pipeline will be up and running by late 2021. According to Norris, the Dominion spokesperson, developers have “extensively surveyed the route of the pipeline to identify and avoid the most sensitive areas and have made over 300 adjustments to avoid public and private water supplies, streams and rivers, wetlands, forested areas, historically or culturally sensitive sites, as well as individual landowner requests.” She said that in light of the 150,000 pages of environmental reports and 75,000 public comments generated throughout the process, the pipeline had the “most thorough and rigorous review of any project in our region’s history.”

“In the end, all agencies reached the same conclusion,” Norris said. “This is in the public’s best interest.”

The courts, however, are calling that conclusion into question. Over the past three years, the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, LLC, has sued landowners in multiple states citing eminent domain, a body of law that governments — and, increasingly, energy companies — use to seize private property that they claim is for public benefit. These cases are still pending but lower courts have stalled the process.

Many communities along the pipeline’s proposed path have expressed their concerns over the project, including the methods Dominion and its partners are using to secure land. This photo shows a sign put up by an activist in Pocahontas County, West Virginia. Lyndsey Gilpin

The Southern Environmental Law Center, or SELC, has challenged multiple permits for the project since the beginning — and won. The most important victory came in December 2018, when the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals found that the U.S. Forest Service violated federal law when it approved the pipeline to cross the Appalachian Trail, managed by the National Park Service, as well as Forest Service land. The ruling canceled the permit and halted construction.

Earlier this year, Dominion appealed the ruling on the Appalachian Trail crossing to the Supreme Court. In October, the Supreme Court decided to take Dominion’s case, and will hear oral arguments in February.

“The Forest Service has never done this before. There is no existing pipeline that crosses national forest land under this statute,” said D.J. Gerken, SELC’s program director. “If they affirm [the lower court’s ruling], there are big consequences for this pipeline, like being rerouted at the very least.”

After the Supreme Court issues its ruling, the D.C. circuit court will hear SELC’s challenge to FERC’s 2017 approval of the pipeline.

Over the past year, I’ve followed the path of the ribbons from West Virginia to North Carolina. I hiked along steep ridges where they were tied to trees; trudged through muddy cattle farms where they were stuck on fence posts. I drove past them as the route curved around churches and homes.

Along the way, I spoke to more than 20 people who lived on or near the proposed route, in addition to scientists, activists, lawyers, and government officials. In some places, I learned that the Atlantic Coast Pipeline has pitted neighbor against neighbor and sibling against sibling, that it has split church communities and broken friendships. In others, I found that it inspired folks to speak out at county meetings, to read every line in an environmental assessment, and to organize protests with strangers who became close friends.

Here are a few stories about some of the humans, wildlife, and places in the pipeline’s path.

The Atlantic Coast Pipeline route begins in the hills of West Virginia in Harrison County, before heading into Lewis County — where a compressor station is being built in Jane Lew, a town with fewer than 500 residents — and then on to Upshur County.

Upshur County, West Virginia

For more than a century, Appalachia has relied on the coal industry, which brought well-paying jobs but left degraded ecosystems and communities in its wake. The coal industry’s sharp decline over the past decade, driven by cheaper natural gas and renewables, has left many central Appalachian counties with some of the highest rates of unemployment and poverty in the country.

“Historically, natural resource extraction has suffered an economic boom-bust cycle,” said Patrick McGinley, an environmental law professor at West Virginia University. “Local communities benefit to some degree, but they also suffer.”

[parallax-image id=”436721″ class=”fullWidth”]

Activists, former miners, and community leaders have long worked to diversify the region’s economy through agriculture, outdoor recreation, renewable energy, and the arts. But the fossil fuel industry has its own plan: natural gas, the most recent iteration of this extractive economy pitched to local officials and communities as an economic silver bullet.

Upshur County sits in the Marcellus Shale region of West Virginia, where eight major pipeline projects are in some stage of construction. Formerly a heavy coal-producing county with just over 24,000 residents, Upshur has a poverty rate of roughly 23 percent — nearly double the national rate. In an effort to attract more industry, county officials endorsed 22 miles of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline in 2017 to run through Upshur in exchange for a promised $2 million in tax revenue per year and hundreds of new jobs. Similar deals occurred all the way down the route, mostly in areas with high poverty rates; ultimately, Dominion and Duke garnered support from most counties along the route.

While the companies behind the Atlantic Coast Pipeline preach economic prosperity for towns like Buckhannon, the county seat of Upshur County, West Virginia, residents are wary of their promises. Steven Johnson

On a November morning last year, with the gray sky spilling a mix of sleet and snow, Kevin Campbell, a gruff 65-year-old retired oil-and-gas industry worker who wears thick glasses, met me in Buckhannon, the county seat, to give me a tour of the pipeline route.

He stopped his van — emblazoned with a giant photo of his face, since he used it during his run for city council — on Brushy Fork Road, next to a pipeline staging area. Campbell showed me where hundreds of 42-inch-wide steel pipes coated in turquoise enamel were stacked in a dirt lot, well before the pipeline was approved by FERC, and left exposed to the elements for nearly four years. (The pipes have since been removed and used for pipeline construction.) The chemical coating that protects the pipe from corrosion is toxic, with the potential to cause birth defects, gastrointestinal issues, and cancer. According to its manufacturer, chemical giant 3M, the coating shouldn’t be kept in direct sunlight for a prolonged period because it has “poor ultraviolet (UV) light resistance.”

It might not work well underground either. Documents obtained by the Southern Environmental Law Center show that earlier this year, pipeline developers had to dig up 10 miles of pipe in northern West Virginia because they failed a corrosion test. In July, federal regulators asked developers for more information about the coating after opponents raised concerns about its impacts on air and water.

As he surveyed the lot, Campbell let out a heavy sigh. “We don’t know what it’s doing to the air or the ground,” he said.

After moving to West Virginia from Florida, Campbell worked for the oil and gas industry on fracking projects, driving millions of dollars’ worth of equipment and chemicals from one site to the next. At some sites, the process was messy, dangerous, and often destroyed the surrounding environment, he said. Cleanup “was somebody’s else’s problem.”

When, in 2014, nearly 10,000 gallons of a chemical used to process coal spilled into the Elk River in Charleston, a major source of drinking water for the area, Campbell started volunteering more with local environmental groups, including the local chapter of the Sierra Club and West Virginia Rivers Coalition.

Campbell was concerned when he heard about how close the Atlantic Coast Pipeline would be to drinking water sources, homes, and a local high school. Working with local organizations, he spent hours each week flying drones, talking to pipeline workers about problems, and taking pictures to monitor construction. He helped provide evidence to West Virginia regulators when they issued their first violation for sediment pollution.

Kevin Campbell — a retired oil-and-gas worker-turned environmental activist — stands in front of an Atlantic Coast Pipeline construction site in Buckhannon, West Virginia. Steven Johnson

An investigation by ProPublica and the Charleston Gazette-Mail last year showed that West Virginia and federal agencies expedited the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, as well as the controversial Mountain Valley Pipeline, slated to run 303 miles from northwestern West Virginia to southern Virginia. (Federal regulators stopped construction of the Mountain Valley Pipeline, which is mostly complete, in October because of unresolved legal challenges.) And while there have been small economic gains for local restaurants and businesses, most experts say it’s not enough to move the needle. The tax revenue wouldn’t provide extensive economic relief, and more experienced welders and industry workers on the construction crews hail from outside the state.

“Despite the promises and opportunities that industry emphasizes, at the end of the day, what’s going to be left are the same concerns: Has surface and groundwater been contaminated? Are the businesses like convenience stores, motels, and pipeline businesses that were created during the boom going to shut down?” said McGinley, the law professor. “I’d say probably, because the majority of investment is on the front end, on development. It’s a short-term profit.”

From Upshur County, the pipeline route heads southeast, through the Allegheny Mountains and Randolph County, crossing into the Monongahela National Forest and Pocahontas County.

Pocahontas County, West Virginia

Last November, I stood in the middle of a two-lane state highway near Clover Creek, one of West Virginia’s beloved trout streams. On one side of a mountain, sections of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline snaked down through a steep, muddy trench. Workers prepared equipment along the shoulder of the road and sections of pipeline were lined up, ready to cross it and writhe up the next hill.

Beneath the steep grades and rounded peaks of the Appalachian Mountains, formed 300 to 500 million years ago, a network of underground tributaries flows through the limestone bedrock, dissolving it over time and creating a lattice of voids that resembles swiss cheese — a topography called karst. Some of these caves are as narrow as a pencil; one of the largest in West Virginia hosts an underground waterfall that’s more than 140 feet high.

[parallax-image id=”436722″ class=”fullWidth”]

Pocahontas County, on West Virginia’s border with Virginia, is full of these waterways. The water that flows rapidly through them emerges cold and clean at springs and streams, creating the perfect home for brook trout, a colorful, spotted fish prized by anglers. The fish seek shelter behind boulders and beneath undercut banks, darting out to feed on insects and other invertebrates above and below the surface. In the fall, they spawn and lay their eggs along pebbly stream bottoms.

Some of the most important waterways for brook trout reproduction are in Pocahontas County, which sits at a high elevation and is less industrially developed than other parts of West Virginia. This county, where Clover Creek flows, is often called the “birthplace of rivers,” since it is home to the headwaters of eight rivers. There are 54,000 miles of rivers and streams in the state, said Nicolas Zegre, associate professor of forest hydrology and director of the Mountain Hydrology Laboratory at Davis College at West Virginia University. But 86 percent of that mileage is headwater streams that are no longer protected under federal law, since the EPA repealed the Waters of the United States rule earlier this year.

Beneath the Appalachian Mountains lies a complex system of caves called karst. They have been carved over millennia by underground tributaries winding through the limestone bedrock. Steven Johnson

“Whatever happens high in headwaters will inevitably impact downstream, where water matters to society,” he said. “What happens in West Virginia has implications all the way down the Potomac River and the Mississippi River.”

Brook trout are like canaries in the coal mine for water quality. Sand and silt from upstream erosion can smother their habitat, reducing both their food sources and reproductive success. When water quality and habitat is degraded, the fish disappear. “This part of central Appalachia really is one of the best strongholds of native brook trout in the region,” said Jacob Lemon, eastern angler science coordinator for Trout Unlimited, which works to protect, conserve and restore North America’s coldwater fisheries and their watersheds. In West Virginia, trout populations are fragmented because development has relegated them to small headwater streams. Without access to larger rivers, brook trout are “more sensitive to localized impacts,” Lemon said.

Pocahontas County, West Virginia, is the home of the headwaters for eight different rivers, providing an ideal home for the economically and ecologically important brook trout. Steven Johnson

The Atlantic Coast Pipeline’s proposed route crosses 40 wild trout streams. Puncturing the wrong piece of earth in this fragile ecosystem, whether by digging for a well, installing infrastructure, or building a home, can cause more subsidence, sinkholes, and rapid movement of contaminants or sedimentation.

If West Virginia’s streams were to become contaminated or degraded enough to damage brook trout populations, it wouldn’t only be an environmental disaster; it could also devastate a small but steady industry in the state. In 2017, sales of trout fishing licenses raised nearly $1 million for the state, and the angling economy enables gas stations, restaurants, lodges, and other businesses to flourish during the fishing season.

“Given the importance of biodiversity and the complexity of the landscape and stream networks,” Zegre said, “this is one of the worst places to do this project if we think about the system as a whole and not just inexpensive energy moving across the state.”

From Pocahontas County, the pipeline would barrel through more national forest land as it crosses into Highland County, Virginia, and then south into Bath County.

Bath County, Virginia

In 2015, the Atlantic Coast Pipeline’s developers had to reroute the project away from two Virginia counties to avoid crossing National Park Service land. The next year they had to reroute it again, around the Shenandoah Valley, because the path crossed the habitat of the endangered cow knob salamander.

Jeannette and Gary Robinson watched the story unfold for months, nervous about what the rerouting might mean for their community in Little Valley, just outside Shenandoah. Little Valley, in Bath County, is a narrow hollow with a cool creek running down the center. Many of the families live on land passed down for generations.

[parallax-image id=”436723″ class=”fullWidth”]

Not long after the decision to reroute the pipeline on account of the salamander, Jeannette sat in her driveway in disbelief, staring at a letter from Dominion saying that her land was about to be surveyed for a potential new route. The Robinsons’ farm, which has been in Jeannette’s family since 1792, is at the head of Little Valley, a quiet, lush corner of Appalachia. While there are no endangered salamanders here, there are plenty of other flora and fauna that scientists and residents are concerned about: native brook trout and an old-growth forest that’s home to a massive 500-year-old maple, as well as spring systems that Virginia officials are worried the pipeline could disrupt.

It’s also the habitat of a tiny organism that has helped stall the project: the rusty patched bumblebee, which in 2017 became the first bee in the continental U.S. to be placed on the endangered species list.

An access road for the proposed route of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline cuts across Jeannette and Gary Robinson’s farm in Little Valley, Virginia. The land has been in Jeannette’s family since 1792. Lyndsey Gilpin

At dusk on a cold night last fall, hours before an ice storm passed through, Gary took me on a walk around their farm. Pausing in a brambly meadow just up the hill from the white farmhouse where Jeannette grew up, he motioned to a thick patch of native grasses. “This is where they found one of the bumblebees,” he said proudly.

In 2017, a Dominion surveyor reported a rusty patched bumblebee in the area while working on the environmental impact statement. Virginia state scientists found a group of them on the Robinsons’ farm about a year later, and Gary found another the next day. The rusty patched bumblebee primarily lives in the Midwest and in Virginia, and its population has declined by 87 percent since the 1990s. Little is known about it, said Chris Ludwig, the recently retired chief biologist at the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, but it’s now one of the state’s top conservation priorities.

“It’s a very rare bee and may be a bellwether for other insects that are rapidly declining,” Ludwig said.

Dominion Energy served the Robinsons with papers in May saying it was going to take their land through eminent domain to build an access road. The proposed pipeline route crosses through Little Valley and up a nearby mountain, with about half a mile of the planned road running along a narrow ridgeline on the Robinsons’ land. Their court dates are scheduled for next year.

[jumbo-content]

[/jumbo-content]

Fortunately for the Robinsons, that same month, environmental lawyers argued that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service permit should be vacated because the rusty-patched bumblebee and three other endangered species — the clubshell mussel, the Indiana bat, and the Madison Cave isopod — were not taken into consideration when the biological opinion was written for the environmental impact statement. In July, a three-judge panel in the Fourth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals revoked the permit, and one wrote in his opinion that the agency had “lost sight of its mandate” under the Endangered Species Act.

“Appalachia is one of the most biologically diverse habitats in the country, and the people who live here in Little Valley, like Jeannette’s family, have lived so lightly on the land over the centuries that it is still able to support animals like the rusty patched bumblebee,” Gary said over tea in their living room. “That whole heritage has passed down to us, and you know, we’re trying to protect it.”

The pipeline route winds north through Augusta County and then back south again, where it would cross the Appalachian Trail and the scenic Blue Ridge Parkway before heading to Buckingham County, where the second of three compressor stations is planned. The route heads south through the rural parts of the state — with a spur to the Virginia coast — before it crosses into North Carolina.

Northampton County, North Carolina

Belinda Joyner wasn’t necessarily surprised when she heard Dominion and Duke Energy wanted to build a compressor station just a few miles from her home in Garysburg in Northampton County, a marshy farming area of eastern North Carolina.

People living in this part of the state have fought off scads of projects posing environmental and public health risks for decades. In the 1980s, a black community protested an attempt to put a PCB landfill in their neighborhood in Warren County, just west of Northampton. The toxic waste was eventually dumped there, but the protests ignited the environmental justice movement. Still, that didn’t stop a variety of other industries from taking root in the region: Northampton County is overrun by concentrated hog farming and is also home to an Enviva wood pellet plant that turns timber from Southern forests into wood pellets to export for Europe’s biomass industry.

[parallax-image id=”436724″ class=”fullWidth”]

Many years ago, Joyner started the Concerned Citizens of Northampton County, going door-to-door to gather members to attend economic development meetings and make calls to environmental groups and lawmakers. “I told people, ‘This is your community, this is your home,’” she said. “Speak from your heart.” Just last year the group successfully organized to stop a coal ash landfill from coming to the county.

But the pipeline has proven harder to defeat.

Parts of Garysburg are in designated “high consequence areas” for the pipeline, where the extent of damage to property or the chance of serious injury or death are significant. Joyner and others are primarily concerned with a proposed compressor station, which is designed to keep natural gas flowing through the pipeline. These facilities are loosely regulated, experts say, and can endanger the communities around them. For starters, the constant vibrations and noise can be a nuisance; worse are the gases they emit, including formaldehyde and methane — a greenhouse gas more potent than carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide is a problem, too. The compressors burn natural gas to run, so exhaust is constantly blowing out of their stacks. There is also a risk of explosions: In 2015, a compressor station in Louisiana blew up, killing four workers, causing tens of millions of dollars in damage, forcing a rural neighborhood to evacuate, and shutting down a highway.

The Atlantic Coast Pipeline would have three compressor stations along its 600-mile route, including the one in Northampton. The 2017 environmental impact statement for the Atlantic Coast Pipeline states that there would be no significant adverse socioeconomic impact from compressor stations. “While they would be permanent facilities, air emissions would not exceed regulatory permittable levels,” the report reads. “As a result, no disproportionately high and adverse impacts on environmental justice populations as a result of air quality impacts … would be expected.”

But two of the stations are being built in predominantly black communities. In addition to the Northampton station, another compressor station is proposed for Union Hill, Virginia, an area settled by freed slaves after the Civil War that has in many ways become one of the epicenters of the fight against the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. Residents, environmental groups, and social justice groups are contesting an air pollution permit granted by Virginia regulators after Governor Ralph Northam removed two regulators from the board who were leaning against it. Opponents say federal regulators need to conduct a review assessing the compressor station’s potential public health impact on the surrounding community or stop the pipeline.

One of three compressor stations for the Atlantic Coast Pipeline is located in Northampton County, North Carolina. While construction of the compressor station has begun, it is currently on hold due to legal challenges. Kate Medley

Low-income and minority communities, like Northampton County, often play host to environmental hazards. An Environmental Protection Agency research team found last year that black people are more likely than any other ethnic group to be exposed to fine particulate air pollution from industrial facilities. Jennifer Richmond-Bryant, a former EPA scientist who was part of the team and now teaches in the Department of Forestry and Environmental Resources at North Carolina State University, said the data is consistent with decades of research that shows hazardous waste facilities and emissions sources are often built near marginalized communities. “Our work follows on that body of evidence,” she said. “Political capital and marginalization are likely to be what drive disparities in burden.”

The Northampton County residents’ fight has largely flown under the radar of national environmental groups. On an unusually warm evening this past February, I visited the compressor station site for a second time. In three months, another massive swath of forest had been clear-cut and buildings were under construction. Some workers were on-site building an Atlantic Coast Pipeline office — which is now complete.

“People feel discouraged,” Joyner said. But new county commissioners, she added, seem more concerned about what citizens want to see in the area, and have been traveling around the county to listen to concerns. Community leaders in Northampton County like her are still battling, organizing with groups around the state and region as they have over the decades on many public health hazards.

“We’re fighting coal ash, we’re fighting to keep cancer out,” Tony Burnette, Northampton County’s NAACP chapter president, said. “And in the end they’re going to blow us up. That’s why we fight.”

Leaving Northampton County, the pipeline route heads through the sprawling farms of eastern North Carolina, past hog and poultry feedlots, across fields of cotton and soybeans. Its planned terminus is in Robeson County along the state’s border with South Carolina.

Robeson County, North Carolina

Last year, Dominion Energy offered four Native American tribes in the Eastern U.S. — the Lumbee Tribe and the Haliwa Saponi Indian Tribe in eastern North Carolina and the Monacan Indian Nation and Rappahannock Indian Tribe in Virginia — $1 million each in exchange for agreeing “not to hinder or delay the development, construction or operation” of the pipeline. In the contract was a waiver of the tribes’ rights to present any claims against the pipeline and a requirement to issue a statement that they had each resolved any issues with developers.

It’s unclear if the Virginia tribes signed the agreement. The North Carolina tribes, which have lived in and around Robeson County for hundreds of years, did not. “I took an oath to uphold the Lumbee way of life and that includes protecting our voice,” Lumbee Tribal Chairman Harvey Godwin Jr. told The Robesonian in 2018.

[parallax-image id=”436709″ class=”fullWidth”]

It wasn’t an easy decision. Opinions about the pipeline have divided the Lumbee, who take their name from the Lumber River that winds through the area. Like many rural places, Robeson County’s economy is struggling. Over the past two decades, it has lost thousands of manufacturing and farming jobs. According to a 2004 research report by a University of North Carolina Wilmington economics professor, a decline in the local manufacturing industry between 1993 and 2003 cost the county more than 18,000 jobs and $713 million per year in income and business taxes. The University of North Carolina at Pembroke brings in young students, but it hasn’t kept the county’s population from dwindling.

On top of the lack of jobs, residents have also had to contend with frequent floods. Many were still recovering from Hurricane Matthew in 2016, which dumped up to 14 inches of rain and caused the Lumber River to overflow. More damage inflicted by Hurricane Florence in 2018 prompted Congress to pledge more than $50 million in FEMA recovery funds.

Donna Chavis founded the Center for Community Action, a Robeson, North Carolina-based social justice organization that has campaigned against the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. Kate Medley

The proposed route of the pipeline ends here in Robeson County, the last stop on my trip through North Carolina. The county government endorsed the pipeline project in early 2016 amid guarantees that it would provide $900,000 a year in revenue from property taxes once completed. People here have heard such a pitch before: According to Donna Chavis, a member of the Lumbee Tribe and senior fossil fuels campaigner with the environmental advocacy organization Friends of the Earth, and her husband, Reverend Mac Legerton, acting director of the North Carolina Climate Solutions Coalition, in an 8-mile radius within the heart of the indigenous community in Robeson County, there are 11 existing or planned natural gas projects.

At a small diner in Prospect, just down the street from a compressor station owned by Piedmont Natural Gas, a subsidiary of Duke, that has leaked in recent years, I had breakfast with Chavis and Legerton. “With the deconstruction of the rural economy, the local politicians and state policy makers are grasping at straws because survivability becomes a priority, not sustainability,” Legerton said. “We’re vulnerable to the money the fossil fuel industry has.”

Chavis said proposals for these types of industrial projects have come and gone for several decades. But the Atlantic Coast Pipeline was a “wake-up call for indigenous people in North Carolina,” she added. Locals in the community have spent years studying the damage the project could cause, recruiting student lawyers to read contracts, poring over environmental justice assessments line by line, and making sure people know about permit hearings.

[jumbo-content]

[/jumbo-content]

The project would cross archaeological sites and other land that the Lumbee consider sacred, as well as several swamps that are part of the larger watershed Robeson County taps for its drinking water. The wetland ecosystem that includes the Lumber River is rich in biological diversity and home to endangered or threatened species such as the red-cockaded woodpecker, the wood stork, and Michaux’s sumac.

These are resources indigenous peoples in the area have relied on for centuries and have fought to protect, but their ability to do so is limited. Congress does not recognize the Lumbee as a sovereign nation and has not allowed them the full benefits of federal protection. “Non-federally recognized tribes are doubly vulnerable,” said Ryan Emanuel, a member of the Lumbee Tribe and professor at North Carolina State University. He said that many Native Americans living east of the Mississippi are members of tribes that aren’t considered sovereign because they have no federal recognition. “Without federal recognition, we don’t have access to protective standards — even substandard ones,” he said.

Piedmont is also planning to build a liquefied natural gas facility in an area where many indigenous people live. Amid the growth of natural gas production, Chavis said she has had many conversations in recent months with people in tribal communities along the East Coast about their “responsibility to environmental integrity.”

“For me, one of the important things that has come out of this, which I hope gets stronger, is that indigenous peoples of Virginia, North Carolina, West Virginia, and South Carolina continue to be able to strengthen their connection to ancestral teachings using an environmental lens,” she said. “Once we’ve given up hope, we’ve given up.”

Crews stage the Atlantic Coast Pipeline before burying it underground in northern West Virginia. Lyndsey Gilpin

There were so many pink ribbons along the route that I didn’t see. Each one could be a conversation, an argument, a promise, a loss: a piece of land traded for too little compensation, a quiet corner of undisturbed habitat, a favorite tree chopped down.

Much of the land the Atlantic Coast Pipeline is set to traverse, and the people who call it home, are already altered by it. Trees are cut, holes are dug, relationships in communities have shifted, and trust in government has been shaken. Many people told me they believe another project like this will likely appear in front of regulators after this one is done — after temperatures rise, after more consequences of climate change take hold, after more pipelines explode or leak. But they’re cautiously optimistic the Atlantic Coast Pipeline could be stopped for good.

Thanks to the start-stop progression of the project, its costs are ballooning, rising from an initial estimate of between $4.5 billion and $5 billion to $7.5 billion in three years, and Dominion executives have acknowledged they’re running into larger hurdles than they expected. Federal regulators allow pipeline companies up to a 14 percent return on investment from customers. In the case of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, utility companies are the customers — so they can charge ratepayers for the project.

“It’s risk-free guaranteed money for them and guaranteed payment from ratepayers,” said Gerken, from SELC.

While the fate of the pipeline is still uncertain, the fight to build it has once again revealed the power that energy companies maintain over low-income and rural people, and the ways in which local officials and politicians enable this power. It has reenergized the decades-long movement against resource extraction and pollution in Appalachia and in the rural South, bringing together racially and socioeconomically diverse stakeholders — conservative landowners, progressive activists, environmental justice advocates, farmers, pastors, business owners, students — from all over the region to fight it.

“This was a particularly badly planned pipeline, and for that reason, it’s had a particularly poor start,” Gerken said. “They chose to blast through some of the most sensitive and protected terrain in the Southeast and subjected themselves to rigorous legal standards they couldn’t meet. Their plan was to use political pressure to bully the project though. Unfortunately for them, we have a judicial system. That’s why FERC has to ask really hard questions. Is this self-dealing, or does it have a purpose?”

A 36-inch-wide piece of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline set up on a flooded worksite in Northampton County, North Carolina. Lyndsey Gilpin

At the beginning of this process several years ago, Gerken said there was no room for error for environmental groups — but things have changed. From this point on, Atlantic Coast Pipeline has to “win everything for this pipeline to succeed,” he said, including new permits from several federal agencies.

“It is now the pipeline company that is up against the clock.”

This story is a collaboration between Grist and bioGraphic, a nonprofit magazine about nature and sustainability powered by the California Academy of Sciences.