What are profits and how do you tally them?

The entire history of accounting exists to answer that question. Fortunately, we don’t have to.

But the piece we ran last week on Apple’s profits — “Why your iThings don’t have to be weCruel” — started a vigorous discussion on the subject among readers.

Our contributor Gar Lipow wanted to make the case that the production of Apple’s popular gadgets isn’t inherently unsustainable and doesn’t have to exploit overseas labor. Several commenters objected to Lipow’s statement that “The single greatest cost component of both the iPhone and the iPad is neither labor nor materials, but profits.” They noticed that the pie charts we published broke down material costs and labor costs for the iPad and iPhone by country but slapped the label “Apple profits” over what seemed to be the entire sum of Apple’s revenue for these products — without taking into account its overhead, design costs, personnel costs, and so on.

They were right, up to a point. Lipow drew his information from a well credentialed and widely disseminated paper [PDF] by a trio of scholars whose previous study of the iPod had garnered wide attention. These papers all examine “value capture” by country, to try to figure out which of the many nations in these products’ international supply chain is benefiting the most. It’s not a simple question. The papers’ authors used the word “profit” on their own pie-charts, which is where Lipow took it from. Reading their text makes it clear they were referring to “gross profit” as opposed to “net profit.”

I’m not even going to begin to tax your attention explaining that distinction here, because in the end it doesn’t matter. Lipow’s piece remains relevant and defensible because, in the end, it makes little difference whether you identify that hunk of Apple’s money on these charts as profit or revenue, gross or net.

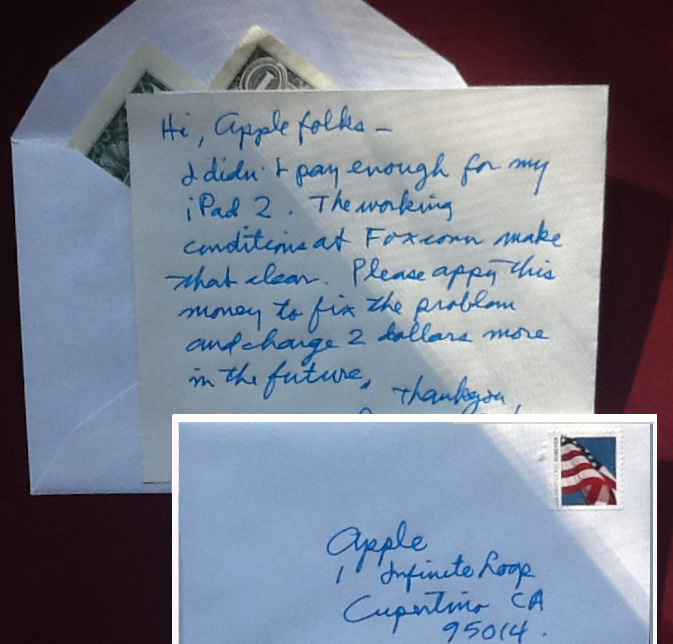

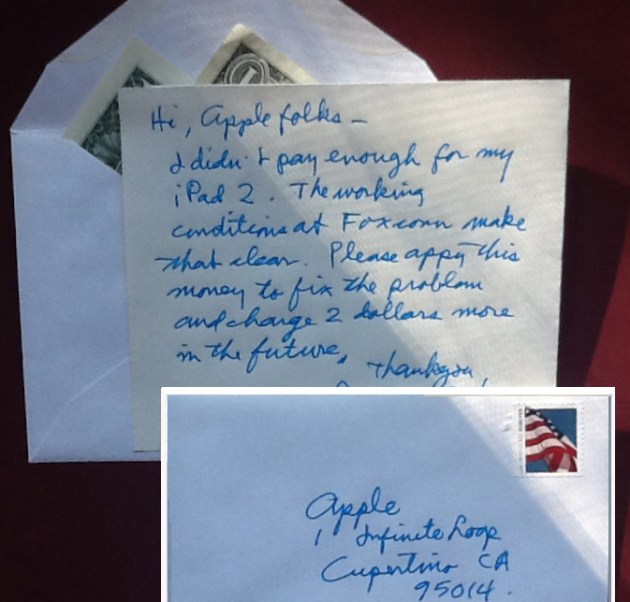

Lipow pointed out that the Chinese labor costs for both the iPad and the iPhone represent approximately 2 percent of the value of these products. Meanwhile, we know that Apple itself is generating profits that, in both total volume and margin, dwarf the norm in its industry. When the company’s cash hoard hit $76 billion last summer, headlines noted that it had more bucks on hand than the U.S. government. (It’s true that Uncle Sam’s till happened to be at low ebb just then.) Apple’s bank balance has since risen to a jaw-dropping $100 billion.

In other words: There’s little question that Apple and its partners could improve the working conditions and pay of their Chinese workers — heck, they could double salaries tomorrow — without substantially altering the economics of the products or cutting deeply into their own profits.

It’s a given, of course, that this will not happen. Corporations maximize profits, not the well-being of their workers. And the workers in question aren’t even Apple’s, they’re a contractor’s.

So it is, under the logic of global capitalism. But this is a choice of our system, not a law of nature. That, I think, was Lipow’s point. While I wish we’d done a better job of labeling our numbers, I think the point still stands.