A new study of African-American residents leaving Austin for the suburbs shows that communities of color are being displaced not just in coastal cities such as Portland and Washington, D.C. but in Texas too. And in too many cases, this can mean a lower quality of life, with less access to amenities such as supermarkets and green spaces.

As Austin’s tech economy has boomed and the music scene has turned it into a hipster mecca, the city’s real estate has grown more expensive. Historically black East Austin has experienced particularly rapid gentrification. Median home sale prices in the area increased more than 50 percent over just the two years between 2013 and 2015.

“Austin’s African American population has been in steady decline for nearly two decades,” notes the study from the Institute for Urban Policy Research and Analysis at the University of Texas at Austin. “From 2000 to 2010 African Americans were the only racial group in Austin to experience an absolute numerical decline during a decade of otherwise remarkable growth in the city’s general population.” Over those 10 years, Austin grew 20 percent and was the third-fastest-growing large city in the U.S., but its African-American population declined by 5.4 percent.

To find out why they left and what it meant for them, Eric Tang and colleagues at UT interviewed 100 African Americans who moved out of Austin, most of them since 1999, but still go to church there.

Why they left

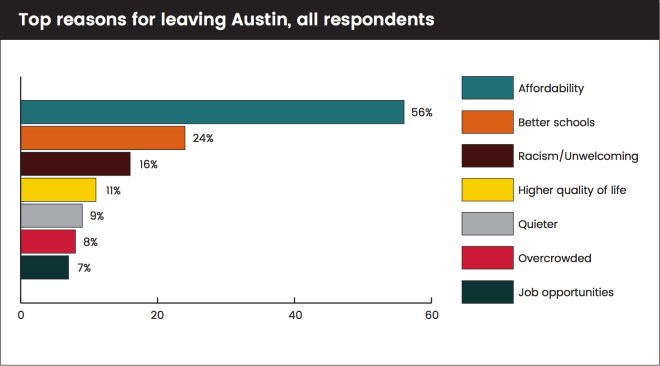

The majority said they were priced out of the city: 56 percent identified “unaffordable housing” as a reason for leaving, by far the most common reason given. That’s not because all of them are poor. The average income among respondents was a solidly middle-class $58,540. Like other hot cities, Austin is becoming unaffordable even to many middle-class families.

The second most common reason for leaving, cited by 24 percent, was schools. East Austin’s schools are highly racially segregated, and the people interviewed believed their children had been getting a poor education in their old Austin neighborhoods.

What they gained and lost

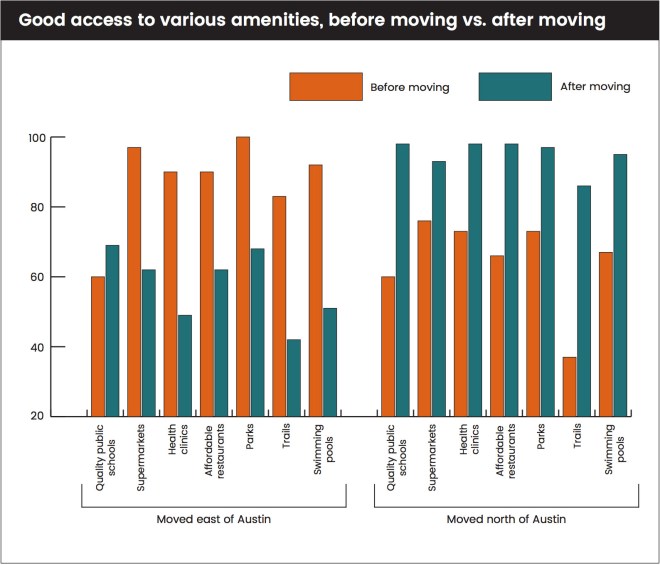

So did the survey participants have better access to good schools and other amenities after they moved? That depends on whether they moved to a wealthy suburb or a less wealthy one, Tang and his coauthors found.

Ninety-eight percent of those who relocated to relatively affluent suburbs north of Austin said they now have access to quality public schools, compared to 69 percent of those who relocated to Austin’s lower-income eastern suburbs. In both cases, that’s greater than the 60 percent who said they had had access to good schools in Austin itself.

But beyond education, the people who moved to poorer suburbs east of the city said they had less access to key amenities — supermarkets, health clinics, parks, and swimming pools — than they did while living in Austin. The experience of those who moved north of Austin was the opposite: Most said they had better access to all those same things.

Most worryingly, the eastern suburbs of Austin also have fewer jobs, meaning that the people priced out of the city are being pushed away from economic opportunity and potentially trapped in poverty.

What this tells us

Suburbs tend to be homogenous, so the ones with richer residents than the nearby big city will have better retail and public services, while the less wealthy ones will have worse services and amenities. This means that the people who need access to services the most are even worse off when they get priced out of a city and into a poorer suburb.

Historically, there weren’t many poor suburbs, so this wasn’t a big social issue, but that’s changing as gentrification in cities like Austin drives up housing prices and drives out lower-income people. Now that suburbs are gaining more residents who lack cars or money for gas, they will have to confront the environmental injustice and public health problems like food deserts and inadequate public transit that have long plagued poor neighborhoods in cities.

Cities, on the other hand, can level the playing field somewhat. They offer the density, population size, and economic integration that can give the poor greater access to everything from healthy produce to trees, even though some neighborhoods are certainly less well-served than others.

Cities like Austin need to figure out how they can control housing costs so that their residents don’t end up farther away and worse off.