My Momma got cancer in her breast,

Don’t ask me why I’m motherfucking stressed, things done changed

— The Notorious B.I.G., in “Things Done Changed” from the album Ready to Die

Yesterday marked the 17th anniversary of the death of “Brooklyn’s finest” hip hop artist, The Notorious B.I.G., a.k.a. Biggie Smalls, who was gunned down in Los Angeles when he was just 24 years old.

Biggie’s murder seemed part of some self-fulfilling prophecy that God perhaps took too seriously. His inaugural 1994 album, Ready to Die, is a series of tone poems illustrating the kind of drug war gunplay that would eventually claim him as a homicide statistic. The Brooklyn rapper imagines multiple scenarios under which his death might occur: In a shootout with cops while pursuing pathways out of poverty that President Obama would not approve of (“Gimme The Loot”); killed by jealous acquaintances who want to rob him for his riches (“Warning”); or, by his own finger on the trigger (“Suicidal Thoughts”).

Biggie’s murder seemed part of some self-fulfilling prophecy that God perhaps took too seriously. His inaugural 1994 album, Ready to Die, is a series of tone poems illustrating the kind of drug war gunplay that would eventually claim him as a homicide statistic. The Brooklyn rapper imagines multiple scenarios under which his death might occur: In a shootout with cops while pursuing pathways out of poverty that President Obama would not approve of (“Gimme The Loot”); killed by jealous acquaintances who want to rob him for his riches (“Warning”); or, by his own finger on the trigger (“Suicidal Thoughts”).

Most of my friends (and Biggie fans in general, I’m sure) took the album as pure artistic liberty, no different than Martin Scorsese’s cinematic canon on mafia life. We no sooner thought that Biggie would actually die in a shootout than we did Robert De Niro would get shot like his character Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver. When Big, whose birth name was Christopher Wallace, was actually killed by gunfire, it stunk too much of life imitating art.

But of all the ways Big imagined himself dying on that album, none of them reflected the real climate of death that existed in Brooklyn at the time, or even today. Deaths for African Americans in Brooklyn usually look less like Wallace’s murder and more like his mother’s life. When he rapped about his Momma having breast cancer, that was true. Voletta Wallace survived two bouts with the deadly disease, in both cases proving that she was not yet ready to die.

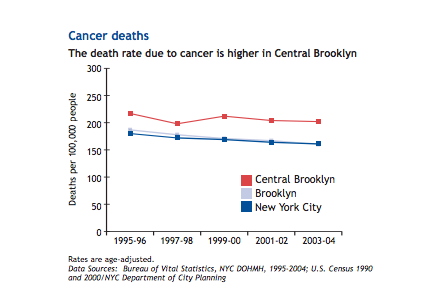

Her health conditions as a black woman in Brooklyn, or even in New York City, were not unique. Cancer was the second highest cause of death in her borough at the time Ready to Die was released, according to a 2002 report from the New York City Department of Health. (I’ll get to the top killer in a second.) From 1992 to 1996, there were 104 cancer deaths in Brooklyn for every 100,000 people. Of the seven leading death causes, homicide was in last place, with 11 cases per 100,000.

All of this is to show that while Biggie and many other young black people were worried about gun-strapped stick-up kids and hustlers, many of their mothers were worried about killers with no guns or faces. As for Biggie, perhaps we should have been asking why he was motherfucking stressed. Had he not been killed by gunshots, his life could have been claimed by stress, which was a primary cause of Brooklyn’s No. 1 killer at the time: heart disease.

Cancer and heart disease are still the top causes for premature deaths in Brooklyn today. Environmental factors have long been suspected as possible causes for both. The National Cancer Institute conducted a study in the 1990s in Long Island (just north of Brooklyn) to examine the role of environmental factors in the high breast cancer rates in that area. The researchers found a “modest increase” in cancer risk due to exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), cancer-causing agents formed mostly from burning fossil fuels. A 2008 study found a link between PAH exposure and heart disease, and concluded that “chronic environmental stress is an important determinant” in cardiovascular disease risk.

The Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn where Biggie grew up is situated among two large former industrial areas — the Brooklyn Navy Yard to the west and the neighborhood of Williamsburg to the north. Starting in the mid-1800s, Williamsburg was a central location for numerous hazardous chemical plants, radioactive waste dumps, and garbage transfer stations.

During the same period Biggie was writing Ready to Die, black folks across the river were organizing with Vernice Miller-Travis and the group WEACT for Environmental Justice to clean up garbage transfer stations in Harlem. At the time, Harlem had some of the highest child asthma rates in the country, and Brooklyn wasn’t far behind. A section of Bedford-Stuyvesant that today is called Harmony Park has held asthma rates that are twice New York City’s average rates, according to New York state’s Department of Environmental Conservation.

The hospitalization rate for asthmatic children in 1990s Bed Stuy was also substantially higher than that for the city, with 1,264 out of 100,000 kids headed to the emergency room, compared to 720 per 100k for the city. Asthma, which scientists tie to air pollution with damn-near certainty, did not spare the young Christopher Wallace nor the adult Biggie Smalls. In fact, in his song “Runnin’ (Dyin’ to Live),” which featured his fellow (also slain) rapper Tupac Shakur, he joked that he couldn’t run from the cops because he’d have an asthma attack.

Biggie rapped that he was stressed about his mother’s breast cancer in “Things Done Changed,” but the reality today is that things haven’t changed that much. Black women are still most likely to die from breast cancer than all races of women, though they are less likely than white women to be diagnosed with it. That mortality gap has widened since the 1990s.

And despite being a prolific rapper with amazing vocal abilities, all accounts show that Biggie had virtually been dying to catch his breath throughout his years as an asthmatic. The rapper was generous enough with us to share his mother’s brushes with death. But we should also unpack that his own life could have ended in ways he never imagined on record. To that point, while Big’s autopsy report showed that it was definitely his assailant’s bullets that killed him, one article found in his possession at the time of his shooting was telling: a Primatene Mist asthma inhaler.

For Lenka McGee (June 4, 1975 – February 26, 2014)