Squeezing people into simple categories is a national pastime. There are optimists and pessimists, Democrats and Republicans, and in the world of public transit “captive riders” (who must take mass transit) and “choice riders” (car owners who need to be lured into the bus).

A recent report from TransitCenter, a foundation dedicated to transportation research, argues that mass-transit officials should stop splitting the world in half. TransitCenter surveyed riders in three cities with a wide array of transit options — Raleigh, Denver, and New York City — and carried out online surveys in 15 more cities. What they found was that most so-called captives are anything but. Two-thirds of “captive” riders used plenty of other ways to get around. They biked, used car-sharing services like Zipcar, and hailed rides with Lyft and Uber.

Since the automobile became dominant in the 1950s, any attempt to put in new public transit has focused on wooing “choice riders” out of their cars, assuming that “captive” riders will use transit no matter what. When the San Francisco Bay Area’s BART line opened in 1972, for instance, it had carpeted, extra-wide train cars and upholstered wool seats designed especially for the tender butts of suburbia. Such frills, an early BART brochure read, would surely “lure the commuter out of the comfort of his automobile.” In modern times, the choice rider is often used as a justification for installing new light rail instead of increasing bus service.

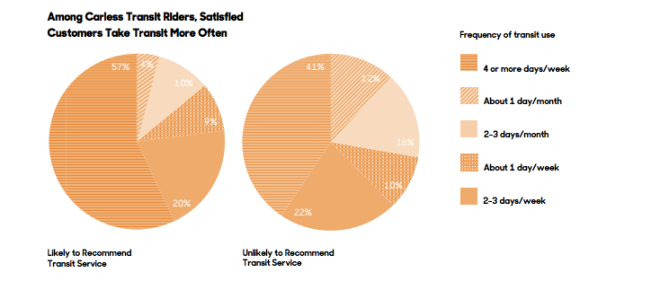

This old approach has it backwards, according to TransitCenter. The survey found that people who were carless were far from captive — the less they liked transit, the less likely they were to use it. Improve their experience and they might take mass transit more often. Luring the so-called captives, TransitCenter reasons, could yield better results.

The frequent riders that TransitCenter surveyed in Raleigh, Denver, and New York City were also serious pedestrians. A transit agency that adds stops in areas that already has a lot of foot traffic, and makes its existing stops pleasant to walk to, will see more ridership. When Seattle added the University Link extension to its light rail line, for example, the new stops in pedestrian-heavy areas caused ridership to boom along the light rail system. In contrast, Washington, D.C. ran its Silver Line out to Tyson’s Corner, a commuter suburb without much foot traffic (or even sidewalks), and got 30 percent fewer riders than expected in the first year.

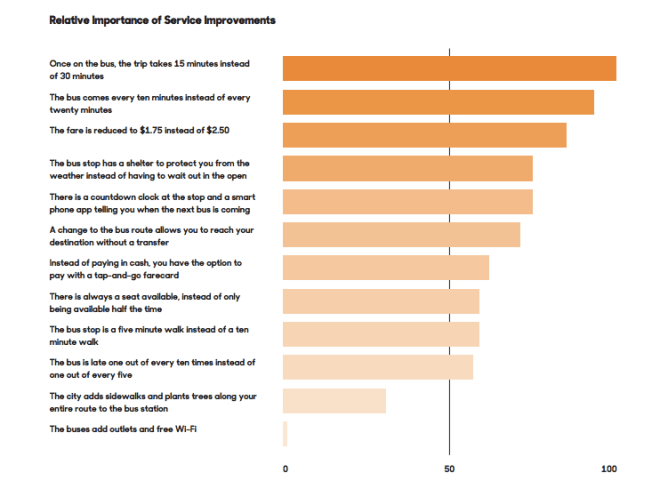

In another part of the survey, Transit Center asked people to imagine a hypothetical bus and asked how they would improve their commute. Their answers were straightforward: They want a bus that got to where it was going faster and ran more frequently.

I stalk free wifi the way that a seagull stalks a picnic. So, I was shocked at how little these survey-taking bus riders cared for frills and high-tech extras. All they want is a bus that shows up on time.

So a word to the transit agencies of America: Don’t get carried away with adding free wi-fi, apps that let you rate your bus line, and other high-tech perks — at least not until you get buses arriving on time. Stop chasing after the riders who play hard to get, and love the one you’re with.