Taking action on global warming can now be measured in lives saved rather than degrees of temperature change. That’s according to a new study published Wednesday in the journal Science Advances, which put a number on just how many heat-related deaths could be prevented in 15 U.S. cities by actually meeting global targets on curbing carbon emissions versus going about business as usual.

One of the deadliest threats posed by the climate crisis is extreme heat. It kills more Americans every year than any other weather-related event. When your body can no longer regulate its core temperature, the result can be heat exhaustion, stroke, heart attack, or a range of other health problems that have the potential to bring about an untimely end. Climate change is projected to bring more back-to-back heatwaves, which are made even more unbearable in cities thanks to the urban heat island effect. Cities and neighborhoods with more heat-trapping asphalt than their surrounding communities tend to experience hotter temperatures. These areas are often where people of color and lower-income residents live, as well.

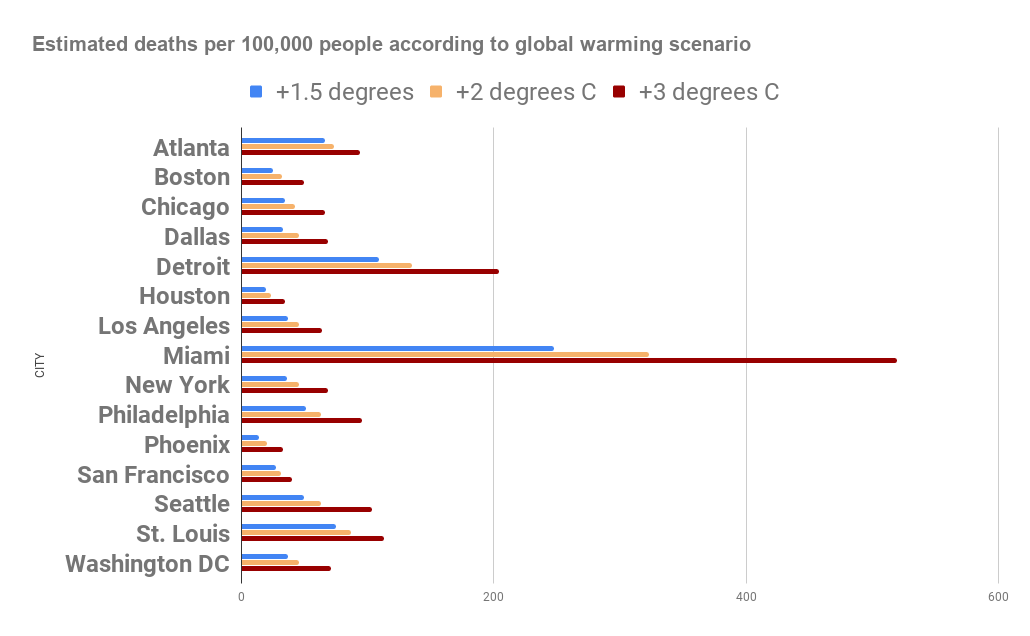

By studying observed temperatures, mortality data, and climate projections, researchers at the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom calculated the estimated annual number of heat-related deaths in several major American metropolises, including New York, Atlanta, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, and Seattle, according to three climate scenarios: If the world adheres to minimum standards set by the landmark 2015 Paris accord (limiting average global temperatures to 2 degrees Celsius — 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit — compared to pre-industrial levels by 2100), if we reach a more ambitious goal touted by many scientists and the most climate-vulnerable communities (stopping at 1.5 degrees C, or 2.7 degrees F, of warming), and if we just keep living our lives as normal (and top 3 degrees C, or 5.4 degrees F, of warming).

Adapted from Lo et al 2019, Science Advances

Heat deaths at +1.5 degrees C (+2.7 degrees F) of warming

Mounting scientific evidence has pointed to 1.5 degrees C of warming being the threshold at which we can avoid the greatest harm. And yes, indigenous peoples, small island nations, and others most impacted by a changing climate have been saying this for years. Now supported by last year’s landmark Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, this is the ambitious target that most climate activists would like to see action move toward.

- Most heat deaths per 100,000 people: Miami (248)

- Fewest heat deaths per 100,000 people: Phoenix (14)

- Highest percentage of heat deaths per 100,000 avoided compared to +3 degrees C: Phoenix (58% fewer deaths)

Heat deaths at +2 degrees C (+3.6 degrees F) of warming

This is the hard target laid out in the Paris agreement. Rewind to 2015: After more than two decades of negotiations, world leaders finally decided to work together to avoid climate catastrophe. Each country pledged to rein in its greenhouse gas emissions in order to keep the world from warming beyond 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures.

Since then, of course, the more ambitious 1.5 degrees C has become a preferred target. Whether that’s realistic is a different matter, as many countries are already lagging behind on their original Paris agreement promises.

- Most heat deaths per 100,000 people: Miami (323)

- Fewest heat deaths per 100,000 people: Phoenix (20)

- Highest percentage of heat deaths avoided per 100,000 compared to +3 degrees C: Phoenix, Seattle (39% fewer deaths)

Heat deaths at +3 degrees C (+6.5 degrees F) of warming

Fast forward four years after Paris, and the world is currently on track to see average global temperatures rise by a whopping 3 degrees C (6.5 degrees F). According to the study, that level of warming could make a deadly difference in many of the cities studied.

- Five cities with the most predicted heat deaths per 100,000 people: Miami (520), Detroit (204), St. Louis (113), Seattle (103), Philadelphia (95)

What makes some locations more vulnerable to heat deaths than others?

Researchers say that a city’s likelihood of suffering heat-related deaths has a lot to do with factors like how densely packed a city is, whether there’s a greater population of more vulnerable groups, like the elderly, and how well it’s prepared to cope with heat emergencies.

New York City, for example, has a lot to gain from sticking to climate targets in the case of a 1 in 30-year heatwave event — 1,980 total heat deaths in a 1.5 C scenario vs. 5,798 total heat deaths in a 3 degree C scenario. Of course, it has the biggest population of the places examined, so it stands to reason that it has one of the biggest tallies of total lives saved if we are able to curb global warming.

There are also regional differences in how each city would fare given its culture and geographic location. Some areas of the U.S., including many cities located further north, will experience a higher average temperature increase that they might not be prepared for. Others, like Phoenix, have a higher percentage of the population already equipped with air conditioning.

What can cities do to reduce the number of heat deaths?

Scientists say the aim of the study is to inform policymakers ahead of the deadline for countries on board with the Paris accord to submit renewed climate commitments in 2020. In addition to curbing emissions, there are many things cities can do to reduce the likelihood of heat-related deaths, like educating people about heat-related illness symptoms, improving public health infrastructure and programs, and increasing access to air conditioning.

Places like New York are already taking steps to cool down, like making sure there’s more green space in heat-absorbing urban landscapes and ensuring that seniors, communities of color, and other vulnerable populations have access to air conditioning. The city has also pledged to cut down its carbon emissions, passing ambitious environmental policies.

Rather than think of climate change solely in terms of your metro area, researchers hope that these numbers inspire leaders to take action on climate change and consider its far-reaching effects. “If this is going on in a country like America, you can bet there’s a significantly worse impact in developing countries,” said co-lead author Dann Mitchell, a climate scientist at Bristol.