New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s affordable housing plan is good for density, transit access, and the environment — but will it deliver the 80,000 units of new affordable housing he’s promised?

The city is in the midst of a housing crisis. The statistics are striking: In 2012, more than one million households in New York City spent at least 30 percent of their annual income on housing and were officially considered “rent burdened.” Since 2009, the median gross rent has increased faster than median renter income. The picture only darkens when we consider that there are nearly one million households in the city classified as “very low income” or “extremely low income,” and there are only 420,000 units in the entire city that won’t stretch their budgets beyond the rent-burdened threshold.

De Blasio’s plan to add 80,000 units of newly constructed affordable housing over the next decade centers around generous (though unspecified) financial incentives and new zoning regulations to induce developers to build bigger buildings with set-asides of between 25 and 30 percent for affordable units. Similar to President Obama with his health-care overhaul, de Blasio has shunned the “public option” — public housing built and maintained by the city of New York — and pursued a market-based approach that seeks to motivate the private sector to do his bidding.

The proposed zoning changes come in two forms, both of which still need to be approved by the City Council. The first proposal is to amend the zoning code to include laxer rules about height limitations and corner lots and define a new affordable housing program. Second, the city is in the process of rezoning East New York, a neighborhood in Brooklyn. This rezoning would take advantage of the aforementioned amended zoning code and permit denser eight- and 10-story buildings in areas of East New York that are currently zoned for modest two- and three-story buildings.

This is smart policy: increasing density near existing lines of transit, reducing costly parking requirements that increase rents, and trading added bulk and height for permanently affordable units. It’s a green approach to accommodating growth without adding greenhouse gas emissions from cars and low-density sprawl.

But zoning should be just the starting point of an affordable housing plan, not the end point. Zoning changes intended to spur development of new affordable housing have been tried in New York and cities across the country, but they haven’t produced anything close to the 80,000 units de Blasio hopes to build.

New York’s previous attempts to use zoning and incentives to encourage the construction of affordable housing met with only modest success. New York City Council Member Brad Lander found that between 2005 and 2013, only 2,769 units of affordable housing were created under a voluntary program that allowed developers to add more floors to buildings than regulations permitted if they incorporated affordable units into their projects. As paltry as that number is, it represents a doubling of the previous program that had been in place since 1987. Clearly, zoning and incentives don’t have a strong record of generating affordable housing in New York. While de Blasio’s proposed program would be mandatory instead of voluntary, it still rests on the appetite of the private sector rather than the needs of the city.

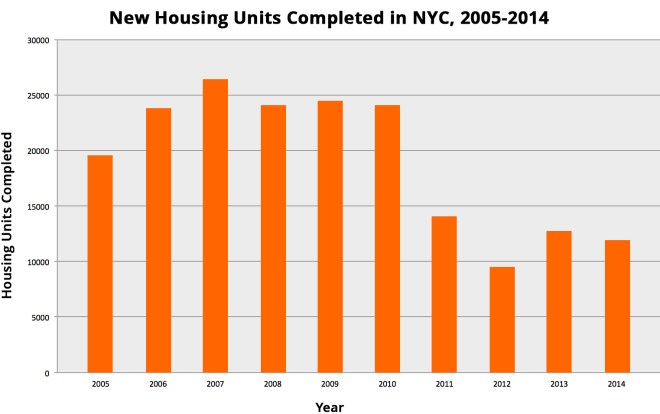

To better understand why the private sector is an unreliable partner, one only needs to look at the number of housing completions in the city over the last 10 years. Between 2005 and 2014, the city gained 190,000 dwelling units, as shown in the following chart.

Based on de Blasio’s goal of incentivizing the private sector to build 80,000 units of affordable housing by mandating that 25 to 30 percent of new units be affordable, the number of total units completed would need to rise to at least 267,000 over the coming decade. And even that doesn’t capture the difficulty of the task at hand: Because the proposed zoning changes would only apply to newly rezoned areas, all of this growth would have to happen in the few neighborhoods that are rezoned after the city council approves the zoning changes.

If these numbers weren’t devastating enough to the mayor’s plans, the real estate market is currently trending in the wrong direction. According to the 2015 Housing Supply Report, the city issued 11,867 certificates of occupancy in 2014, which was down 6 percent from 2013. So to achieve de Blasio’s goal, we not only need to reverse the course of the housing market, but also average two and a half times more construction each year over the next 10 years than the city saw in 2014. The math is simple, and it just doesn’t add up to a more affordable New York.

The problem with an affordable housing construction plan relying solely on the private sector’s ability to produce housing is that it leaves the city vulnerable to unforeseen shifts in the market that dampen enthusiasm for new construction. (Take another look at the chart above to see the wide range of yearly outcomes.) Yet no matter what the market brings, people will still need housing.

So while de Blasio the “progressive” has picked aggressive targets for his affordable housing plan, as it is currently constituted it has virtually no chance of achieving its stated goals. If the mayor wants to get serious about affordable housing — and there is room for debate here — he also needs to consider building public housing, taking on the details of regulations and the building code, such as the rules governing accessory units, and engaging leaders in the broader region. Merely rezoning portions of the city and providing incentives for developers will not ease the financial burdens of most families in East New York, the South Bronx, or Washington Heights.