Last month, in a historic vote, four of New York City’s five Borough Boards — including the Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, and Queens — rejected Mayor Bill de Blasio’s 10-year housing plan. The Borough Boards, composed of City Council members and community board leaders, don’t have final say on the matter; that lies with the City Council. But these votes, which are the result of a year-long grassroots organizing campaign against de Blasio’s plan, may well predict its fate when it comes before the City Council early next year.

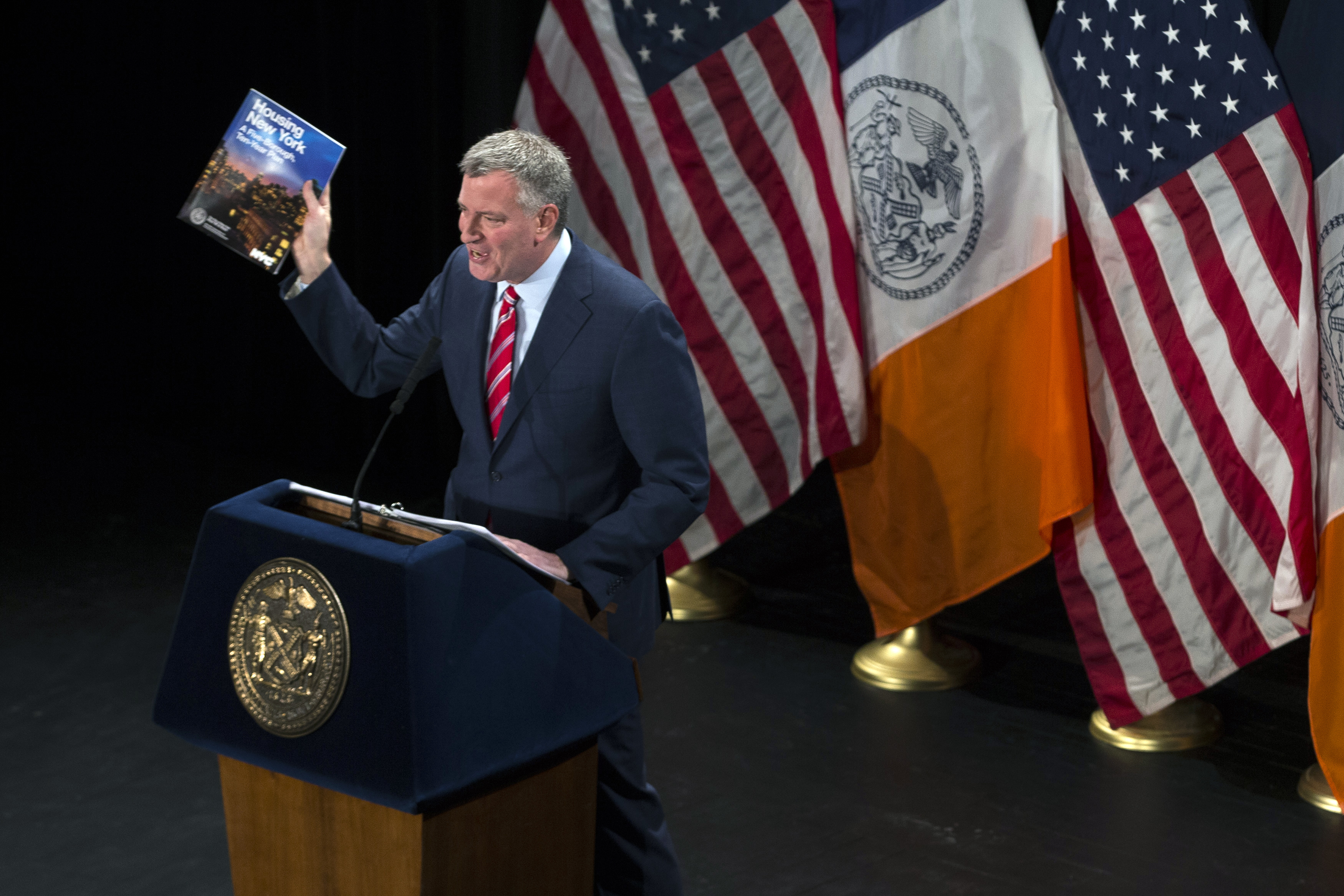

On May 5, 2014, de Blasio first announced his housing plan, touting it as a 10-year effort to combat New York’s affordable housing crisis. After running on a campaign to tackle income inequality in the city, he promoted the housing plan as something that would do just that, alleviating the pain of exorbitant rents felt by many of the city’s working people by preserving or building 200,000 affordable housing units.

Despite the promises, the question remained: Affordable to whom? If you scratch the surface, you quickly see how easily the plan — despite its announced goal of solving the housing affordability crisis — could promote gentrification instead.

De Blasio’s plan includes two stated goals: to preserve existing housing and build new housing. To achieve the first goal, the plan calls for defending tenants against landlord exploitation, strengthening rent laws, and providing more money to public housing. It’s with goal No. 2 that the plan opens the gentrification door.

The de Blasio plan calls for rezoning much of the city, allowing developers to build more and build higher. In return for that, it requires them to provide a certain percentage of “affordable” apartments — a concept known as Mandatory Inclusionary Housing.

“Affordable” here is defined as affordable for people earning a certain percentage of the Area Median Income — an average of the incomes all across New York City, Westchester, Putnam, and Rockland counties. But incomes vary drastically by neighborhood, and suburban counties skew the average income upward, so if you live in a lower-income area, this standard of affordability may still be way out of reach. Conveniently, the neighborhoods the city has decided to rezone first are the very ones where the average local income is a lot lower than the Area Median Income: East New York, East Harlem, Long Island City, The Bronx’s Jerome Avenue, Staten Island’s Bay Street, and Flushing West.

Earlier this month, comptroller Scott Stringer released a study assessing how the de Blasio housing plan would affect the affordability crisis. Focused on East New York, Stringer founded that “the City’s own data shows that the current plan could inadvertently displace tens of thousands of families in East New York, the vast majority of whom will be unable to afford the relatively small number of new units that will be built.”

The numbers were glaring: 84 percent of residents in East New York wouldn’t be able to afford the market-rate housing units that the plan would bring into the neighborhood, and 55 percent couldn’t afford even the “affordable” units. Even worse, the study found that the plan would not preserve affordability in the area: The 50,000 low-income residents living in market-rate apartments in East New York would be at risk for displacement because of the increase in higher-income residents in the neighborhood. Numbers like these put weight behind opponents’ charge that the de Blasio plan will fuel gentrification in the city’s working-class neighborhoods.

When de Blasio’s plan was announced in 2014, grassroots organizers almost immediately sprang into action across the city. De Blasio ran on a progressive platform and raised hopes that he might chart a new course for New York housing, but many organizers for affordable housing don’t see his plan as being very different from those of the builder-friendly mayors who preceded him — including his immediate predecessor, Mike Bloomberg.

“De Blasio’s plan … is very much like Bloomberg’s plan,” Alicia Boyd of the Movement to Protect the People, one of the groups in the Brooklyn Anti-Gentrification Network coalition, told Grist. “[It] will not get you affordable housing but will just continue to do what the Bloomberg administration plan has done, and that is continue the major division between the haves and have-nots in our communities.”

Tom Agnotti, a professor of urban affairs and planning at CUNY Hunter, compared the two mayors’ plans: “Bloomberg introduced voluntary inclusionary zoning and it was mostly ineffective, producing few units of affordable housing. De Blasio proposes mandatory inclusionary zoning, but it is not likely to create significantly more units of housing and they, too, may not be truly affordable when developers get done with it.” As Agnotti sees it, all three plans use the process of rezoning to further displacement, taking existing affordable housing units off the market faster than they create new ones.

With this assessment in mind, organizers across the boroughs began to raise awareness of how the main sections of the housing plan would affect their neighborhoods. The Bronx Coalition for a Community Vision organized community-visioning sessions, not only to break down how the housing plan would affect Jerome Avenue and its residents, but also to build a grassroots movement to create a new housing plan from the ground up.

In Brooklyn, organizers from the Brooklyn Anti-Gentrification Network, the Movement to Protect the People, and the Crown Heights Tenant Union began to attend community board meetings, sign up for committees, and raise awareness by disseminating a breakdown of the plan that summarized how it would affect specific neighborhoods. They condensed de Blasio’s 116-page plan into a 10-page version and a three-page summary that the average person could understand.

“We organized through education,” Alicia Boyd said. “We made sure we were a part of the ULURP process [a committee of each community board that works on zoning]. All the work really happens at the committee level and they make a recommendation to the general board.” Boyd realized that the main challenge was “really getting people to understand what the text amendment is after getting past the [jargon].” Organizers from Brooklyn were also keeping in contact with peers in other boroughs, extending their political education beyond just their own neighborhood or community board.

Boyd also worked to hold public officials accountable. When the city planner of the Brooklyn Borough President’s office presented the housing plan during a community board meeting, Boyd insisted on videotaping the presentation to hold officials accountable. The result was that, even though most of the community board was appointed by the borough president, and Brooklyn’s president, Eric Adams, has been very pro-development, the final vote was against the action. “The community was educated and knew what questions to ask,” Boyd said. In the Bronx, Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens, an overwhelming majority of community boards voted to reject de Blasio’s plan, leading to the four borough boards voting “no” as well.

Still, the fight is far from over. The City Council must vote in early 2016. Many activists see the next step as organizing constituents to put pressure on their council members through letters, phone call drives, petitions, and demonstrations.

“It’s going to be important that grassroots organizers such as ourselves … place pressure on our council person, demanding they say ‘no,’” Boyd said. But she also acknowledged the reality of the situation: “We are not foolish enough to think that our political representatives are really representing us. So much of the real estate [industry] has control over our representatives because of how much they donated … we are aware that it’s going to take more than just a phone call.”

The mayor’s office has acknowledged such concerns while continuing to praise the housing plan. “We simply can’t serve the people of this city if we keep doing things the way they were done before. So our plan is moving forward — it’s moving forward aggressively,” de Blasio said last week.

All this begs the question, what plan would work in New York City to solve the affordable housing crisis, halt gentrification, and create a more inclusive city?

Tom Agnotti says the answer is more public housing. “If [the] government were to build the housing itself with capital funds, it would end up costing government much less than the other schemes which depend on private funding. This is how public housing was built. This is also the way to reach those who need the housing the most — the very low-income and homeless — though public housing [also] include[s] a large segment of working households with moderate incomes.”