When temperatures in Oregon hit 116 degrees Fahrenheit late last month, Portland resident Scott Kerman found he couldn’t stand outside for longer than 10 minutes without feeling like he might collapse. But his thoughts didn’t dwell long on his own discomfort. He was more worried for the city’s homeless population, which is especially vulnerable to extreme weather like heat waves.

“Climate change is a significant part of the houseless crisis and it hasn’t always necessarily been at the forefront when we talk about houselessness,” said Kerman, the executive director of Blanchet House, a nonprofit group that provides free meals, housing, and other services to housing-insecure Portlanders. “If we’re going to have colder winters and hotter summers then we have to be prepared for people who are unhoused or poorly housed continuing to die.”

At least 71 people are confirmed or suspected to have died of heat-related causes in Multnomah County — where Portland is located — during the weeklong June heat wave that shattered temperature records in Washington, Oregon, and the Canadian province of British Columbia. The actual number of deaths associated with the heat wave was likely much higher than the current count, Multnomah officials say, and is expected to rise as the county releases more information in the coming weeks.

While it’s not yet clear how many of those deaths occurred among people experiencing homelessness, not being able to access air conditioning or take shelter indoors is a known risk factor for serious, heat-related illness. Those conditions don’t just apply to people living on the streets — multiple deaths were reported among low-income housing residents amid the heatwave.

From his vantage point working with housing-insecure Portlanders, Kerman said the heat wave’s deadly impact was months in the making. Instead of investing in more resources to protect people living outside from extreme weather, advocates assert that the city has prioritized anti-homeless policing efforts, treating tent encampments as threats.

In 2018, An Oregonian report found that more than half of the arrests made in Portland involved people experiencing homelessness, despite the fact they make up just 3 percent of Portland’s population. In subsequent years, those homeless arrest numbers have continued to be disproportionately high. The compounded risks of homeless and extreme weather has not necessarily inspired leniency in the matter. In April, Robert Delgado, a man living on the streets of Portland’s Lents neighborhood was killed by a city police officer after Delagado allegedly got in an altercation with an employee at a local business. During the heatwave, that same neighborhood (which has seen an increase in the local homeless population over the past year) had the highest number of heat-related deaths in the county. It was also one of the few Portland neighborhoods that did not have a cooling center available for residents.

Kerman said it’s important for officials to see people without stable housing as members of the community in need of dedicated resources, not extra policing. From the COVID-19 pandemic to last Fall’s smoke-filled wildfire season, the past year has been particularly hard on the people Blanchet House serves. “We’ve been in crisis response mode since mid-March of 2020,” Kerman told Grist.

Organizations like Blanchet House have had to stop up to fill the gaps in homeless-specific services. When the COVID-19 pandemic swept through the city last March, Blanchet House upped its meal service by 60 percent, distributing more than 2,000 meals every single day. During the June heat wave, the organization quickly moved to distribute cold water, reusable bottles, water-rich produce, and heat-protective clothes.

Blanchet House workers distribute cool drinks to people experiencing homelessness during the June heat wave in Portland, Oregon. Images courtesy of Blanchet House.

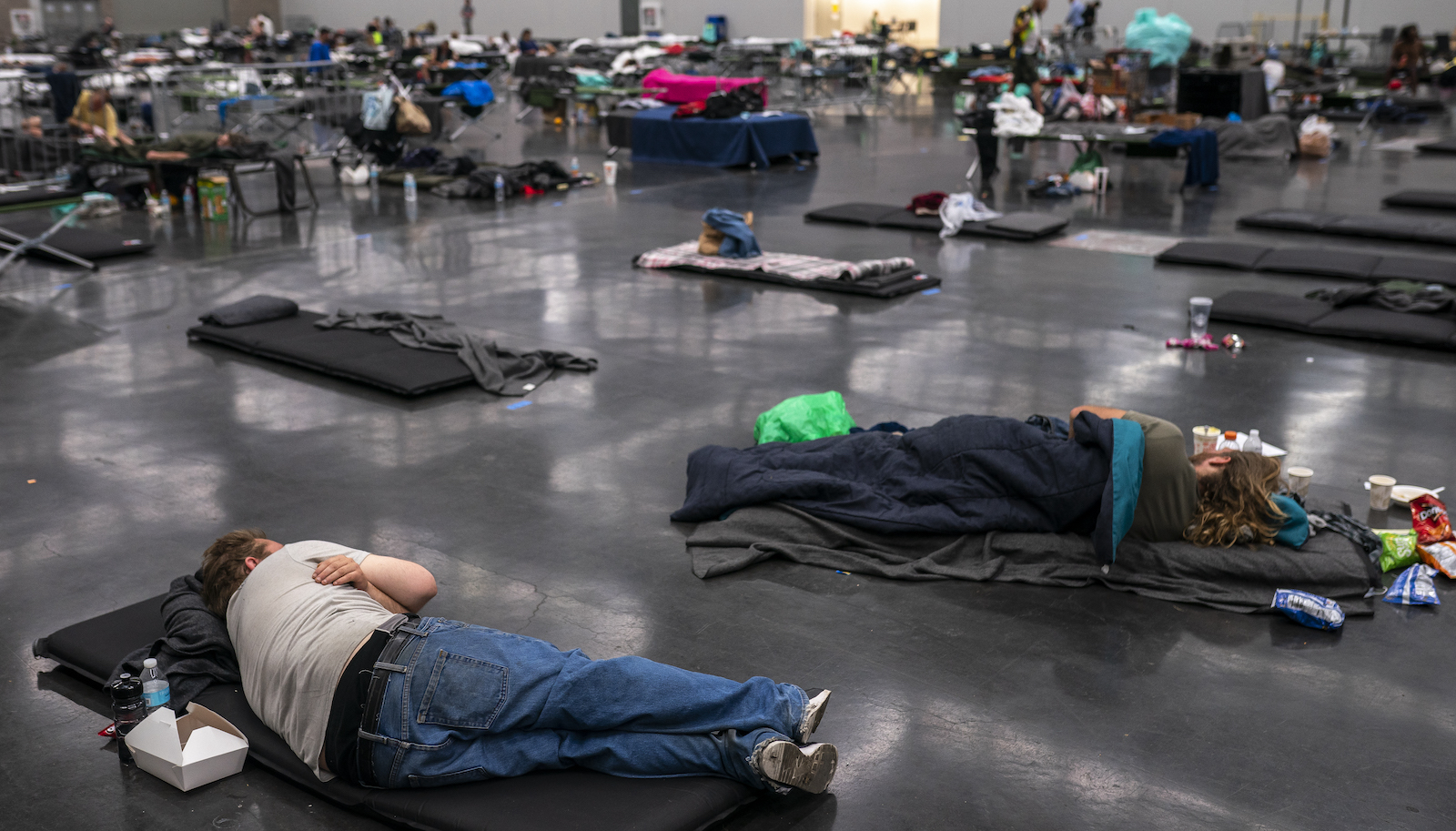

But serving people experiencing homelessness isn’t just about having supplies on hand, Kerman said, it’s about meeting people where they are: Even if support services like shelters and cooling centers were opened up quickly for people, there could still be a plethora of reasons people without shelter would be unlikely to use those support services.

“These environments can be really triggering,” Kerman said. “They’re noisy and crowded, don’t offer the best support for people experiencing chronic mental health or physical illnesses, and leave people with the fear they’ll have to leave all their belongings behind on the streets,” especially because police officers have been known to confiscate people’s possessions and clear housing encampments.

But even though cooling centers aren’t ideal environments for everyone, having access to them can be life-saving — especially with more heat potentially on the way. Regional temperatures usually peak in July — a fact of which Kerman and other advocates for homeless populations are fully aware.

“There will be more heatwaves, if not this year then next, and there will very likely be dangerous wildfire seasons,” Kerman said. “And people are trying to say that the worst of the pandemic is behind us, but for people who’ve lived on the street this whole year and experienced both the climate crisis and this health crisis, things may never get back to normal.”