I don’t bike. There’s no real reason for that beyond the fact that I’m not very coordinated, and I feel like I fall off a bicycle every time I get on one. (Block Island, 2011: Attempted to bike up a minor incline, fell over within two wheel rotations. Mendoza, 2009: Crashed into a ditch on the side of the highway, lost 200 pesos that fell out of my pocket, cried.) Personally, I’ve always felt more comfortable getting around on two feet than two wheels, even if it takes twice — or thrice — as long to get anywhere.

But in my social circle, I’m absolutely in the minority — in fact, I’m regularly surrounded by (braver) women who love riding bikes for the pure freedom it allows them, and swear that there’s no better way of getting around. Both environmentally and economically speaking, it’s hard to beat — especially for city-dwellers.

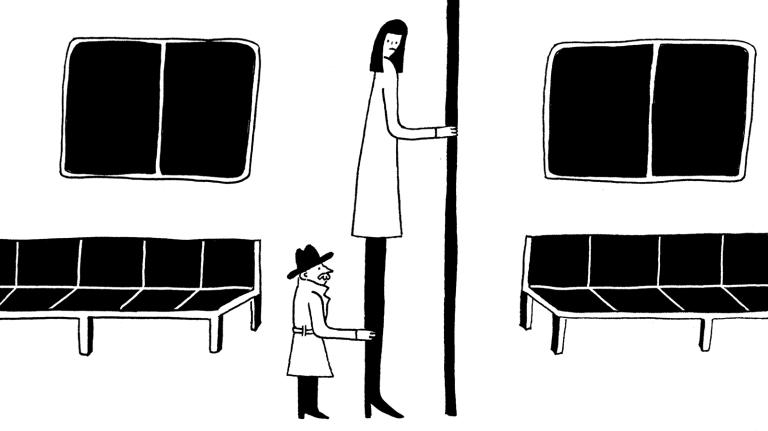

But as with anything that women do in public spaces, the simple act of getting on a bike and pedaling down the street opens us up to unwanted comments, sexual advances, and even violence. Because my own velocipedic career is so pathetically limited, I set out to ask others about their experiences of biking as a woman.

This response, from Seattle bicyclist Liz Rush, stood out to me: “Biking and sexual harassment has always been a weird space, because cycle men will absolutely deny that it ever happens (yeah, right) and sometimes it’s so graphic I can’t believe it.”

For anyone who might deny that this kind of harassment exists, here’s what the experience of riding a bike as a woman looks like on a daily basis:

In New York: “I get comments about my legs and ass and men telling me I should ‘ride’ them instead of my bike or that they like to see me sweat. It’s vile and I shudder to think of what women and girls younger than me — I’m 25 — hear from men like that.”

In Philadelphia: “I had my ass slapped by someone in a car driving beside me. I broke their side mirror off at the next intersection.”

In Toronto: “A guy in the passenger seat [of a passing car] grabbed my ass while I was riding my bike. I bet they laughed. I tried to stay on my bike.”

In Washington, D.C.: “I constantly get hassled while locking up my bike. Men saying ‘Mira, Mami, lemme show you how to lock up your bike,’ while grabbing my bike, then calling me a bitch or worse when I ignore them.”

However, almost every woman who wrote in to share an anecdote of sexual harassment also said that her bike helped her build a sense of empowerment and autonomy.

“When it’s late at night or if I’m traveling through an area where I feel less safe, I often choose to ride my bike rather than travel by public transit or on foot,” says Ngani Ndimbie, Pittsburgh bicyclist and communications manager at BikePGH. “The speed at which I travel on my bike emboldens me. I feel more comfortable zooming past cat-callers, leaving them many yards behind in just a few seconds. That said, my feelings of disgust (sometimes fear) usually stay with me for a few more blocks.”

Like Ndimbie, many women specifically mentioned being able to quickly get away from harassers or attackers as a significant benefit of riding a bike. But — with reason! — they’d also describe how the experience of having to flee from the aggressive men left them shaken and upset. For women who bike, sexual harassment has been normalized as a reality of daily life, but that doesn’t mean that it doesn’t still have the power to frighten or threaten them. Even if it happens every day, coming face to face with a stranger who feels entitled to some level of ownership of your body is terrifying.

“Fundamentally, this is a transportation justice issue, especially when we’re talking about women’s access to bikes,” says Zosia Sztykowski, director of community outreach for the D.C. organization Collective Action for Safe Spaces. “[Biking] is an inexpensive, environmentally friendly, super-accessible way to get around cities, and the more open we can make that, the better for everyone. But [harassment] really does inhibit the way that women move around the city. A lot of them get on the bike in the first place in order to avoid the harassment that they experience while they’re walking. But the more we work on this issue and the more we ask them to come out and tell their stories, the more we’re realizing that that harassment follows them off of the sidewalk.”

But listen closely, and you’ll hear the swelling chorus of biking women around the world saying, “Enough of this bullshit.” It’s the sound of women in many different cities banding together and insisting on better treatment at the hands of strange men. And they’re finding that there’s more strength in numbers than in the most muscled paragon of Hummer-driving machismo you’ve ever had the displeasure of meeting.

Sztykowski has been organizing local workshops for women bikers to empower them to deal with rampant harassment. “In these workshops, we give people some kind of easy tool that they can use when they’re in these situations themselves. We also really emphasize bystander intervention — saying something when you see something happening to another person. And finally, we emphasize working within your community — your friend group, your family, workplace, everywhere — to try to change the culture that makes this behavior okay. Because fundamentally, that is the only approach to stop it.”

I spoke with Rebecca Susman, membership and outreach director for BikePGH, Pittsburgh’s bike advocacy organization, about why she started the organization’s fairly new Women and Biking program. “The impetus for starting the program was that there’s this question out there a lot: ‘What is the right response for women to have to harassment while riding?’ The discussion should be more about why is this happening in the first place — what makes this culturally acceptable? And there isn’t a simple answer.”

The program has hosted a forum and several workshops to bring women of all ages and backgrounds together so that they can share their own experiences of being women bikers.

“I was listening to women tell their stories and just try to grapple with the sexualization of our bodies — how they’re something that other people feel entitled to — and what that means for us,” says Susman of the workshops. “And it was just story after story of harassment and of dealing with it in all different ways. Really, it was very dependent on where they were, and what the situation was, in terms of why they would feel safe or unsafe.”

When I spoke with Hollaback! co-founder Emily May last week about dealing with sexual harassment on public transit, she emphasized the importance of storytelling in helping women come to terms with their own experiences. In that regard, the Women and Biking program has also started a zine night in partnership with the local Carnegie Library. “All the women who attend these workshops create their own [zine] pages to share their own stories of street harassment, of biking in skirts, of why they love to ride – basically, of their lived experiences in a male-dominated culture.”

One of the issues of harassment of women on bikes is that beyond the gendered power dynamics at play, there’s also the clear hierarchy of vehicles in traffic. When a car and a bike crash into each other, which one do you think is more likely to come out unscathed?

“When you really start talking about it, women are still experiencing a different sort of harassment when they’re on their bikes,” says Kate Ziegler, co-director of Hollaback! Boston. “It’s one that has perhaps even a greater physical threat when it’s car vs. bike. We want to look at how that can change the threat that we feel and the transit choices that we make.”

Like Susman and Sztykowski, Ziegler is in the process of organizing educational and community-building workshops. “We really want to have these workshops to continue and support that kind of conversation in the city over the power dynamics in play, and how those two things are not actually different,” she says. “[We’re exploring] how street harassment and harassment on bikes is similar, and especially how the intersection of the two can be really alienating and make people feel really vulnerable on the streets.”

With so many of these workshops popping up around the country, I had to ask: Are they really having an impact for the women they’re serving?

“Part of what’s so powerful about bringing women together is realizing that there’s a kind of universal experience that many of us have in riding,” says Susman. “[Organizing our workshops] was a small step in opening the discussion, and a small step towards empowering us to have a voice. That voice needs to be heard in order to create some great change, to create a safe culture for us to be in.”

“And I was just really thrilled to participate,” she adds. “It was one of the best days of my year.”

Thank you to all of the women who wrote in to share their experiences.