As we take climate change more seriously, we’ll need better ways of measuring carbon emissions. That doesn’t just mean reporting and monitoring systems, but also better conceptual models, a sense of how best to compare emissions between regions or countries.

As we take climate change more seriously, we’ll need better ways of measuring carbon emissions. That doesn’t just mean reporting and monitoring systems, but also better conceptual models, a sense of how best to compare emissions between regions or countries.

Among other things, better metrics will allow us to craft more sophisticated policy. The Kyoto arrangement — “let’s all go back to where we were in 1990” — is, to put it kindly, a blunt weapon, insensitive to participating countries’ varying levels of wealth, population trajectories, native industries, and energy needs. Expectations for any country to reduce its carbon emissions ought to be sensitive to its individual circumstances.

So we need richer, more nuanced ways of figuring out who’s doing well on carbon and who’s doing poorly. That brings us to an interesting recent paper in American Scientist called “Accounting for Climate in Ranking Countries’ Carbon Dioxide Emissions,” by Michael Sivak and Brandon Schoettle. Their insight is simple: Carbon emission rankings ought to be adjusted to account for local climates. Sweden uses more energy to keep people at a comfortable temperature than, say, Greece does, but that doesn’t mean Greece is doing better than Sweden on climate policy. It just means Sweden is really cold! That’s not Sweden’s fault. We need some way of comparing Sweden and Greece that doesn’t give Greece an unfair advantage for the happy accident of being located on the Mediterranean.

So Sivak and Schoettle have developed rankings that take into account “the general heating and cooling demands that are imposed by the climate of a given country.” How does that change things? They have a fascinating chart on this, but it takes some explaining.

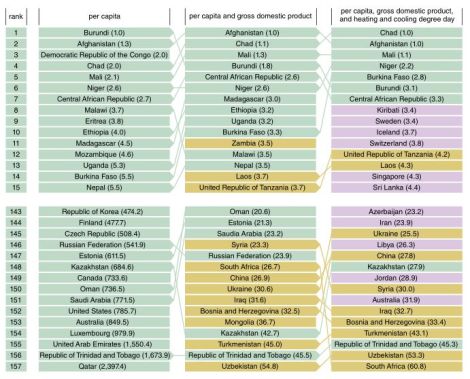

In each column of the chart below, the top 10 lowest carbon emitters are on top, the highest emitters on bottom. In the left column, countries are ranked purely by per capita emissions. In the middle column, they are ranked by per capita emissions combined with per capita GDP. In the right hand column, they are ranked by per capita emissions combined with per capita GDP combined with ” a population-weighted average of the total heating and cooling degree days.” Colors show new entrants. (Click to embiggen.)

A couple of things jump out at me. Sweden, Iceland, and Switzerland, three cold countries with strong climate policies, emerge as low emitters once they are forgiven their coldness. Australia becomes one of the big emitters. And the United States, a top emitter on a pure per capita basis, falls off that list when GDP and climate are taken into account.

Sivak and Schoettle tease out more effects of the climate data:

Taking climate into account improves emissions rankings for countries with relatively high heating and cooling degree days. For example, the United States moves from the 110th spot (when only population size and economic output are included) to the 100th spot (when climate demands are considered as well); the United Kingdom moves from 63 to 58, Germany from 75 to 55, Sweden from 27 to 9, China from 149 to 147 and India from 125 to 116.

But not everyone comes out for the better under the new approach. Countries with relatively low heating and cooling degree days get a less favorable ranking when climate is added into the equation. Among the countries with a substantial worsening are Australia (which goes from 126 to 151), Brazil (52 to 75), Israel (48 to 76) and Mexico (93 to 117).

Huh. Turns out Australia and Brazil have been coasting on their good looks weather!

Are there implications here, not just in terms of fairness in international negotiations, but in terms of national policy? I think there are. It’s worth examining an assumption expressed earlier on in the paper:

The population of a country cannot choose the local climate, of course; that is determined by geographical location.

This is obviously true on one level. The U.S. cannot change its “average of heating and cooling days.” What can anyone do about the weather?

But that’s not to say the U.S. is powerless over where people settle within it. There are temperate places and places of extreme warmth or cold in the U.S. People could move from the latter to the former! I was once talking about this problem with Matt Yglesias, in the context of Chicago’s efforts to reduce its emissions, and he said, “the best thing Chicago could do for the climate is to encourage people to leave Chicago and move to Boca Raton.”

That’s … [shudder] … awful. But there’s some validity to it. Obviously governments aren’t going to start engineering mass internal migrations, at least not unless things get really bad really fast. But it’s not crazy to think that, say, the tax code might be weighted to encourage settlement in temperate areas. It’s not crazy to think that population density in temperate areas might become a policy desiderata. Perhaps one day we’ll see migration to temperate areas as a powerful climate policy lever.

It sounds a little crazy now, but lots of things that sound crazy now are going to sound a whole lot less crazy once the climate sh*t hits the fan. Meet y’all in Boca Raton?