Cross-posted from Climate Progress.

The revolution will be televised. So will the post-apocalyptic fight to feed ourselves on a ruined planet.

Those are two key themes of the wildly popular young adult (YA) trilogy that begins with The Hunger Games, whose movie version comes out this week. The trailer gives the key plot points:

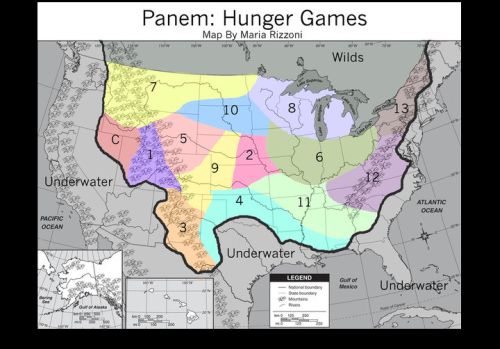

After what seems to be a climate-driven apocalypse, Panem, “the country that rose up out of the ashes of the place that was once called North America,” is divided into a capitol and 12 districts, who launched a failed revolution many decades earlier.

The annual Hunger Games are televised and the rules are simple:

In punishment for the uprising, each of the 12 districts must provide one girl and one boy, called tributes, to participate. The twenty-four tributes will be imprisoned in the vast outdoor arena that could hold anything from a burning desert to a frozen wasteland. Over a period of several weeks, the competitors must fight to the death. The last tribute standing wins.

The winner “receives a life of ease back home, and their district will be showered with prizes, largely consisting of food,” all year round.

This is “bread and circuses” combined — by design — since that famous phrase comes from the Latin panem et circenses (also “bread and games”).

The books have sold some 10 million copies globally — and the author, Suzanne Collins, is the “best-selling Kindle author of all time.” They are a shrewd combination of standard YA fare — another love triangle between a girl and two boys … really? — and pop-culture riffs. You have the extreme version of reality shows like American Idol and Survivor. You have the young girl who reluctantly grows into a ferocious killer, a tradition which started with Buffy and Nikita (if you have to ask … ) and now seems to be found in almost every other movie.

The books also had some fortunate timing for the author in terms of catching the zeitgeist, since perhaps the core theme is the 99% (the 12 districts) vs. the 1% (Panem), the poor and underfed vs. the rich and overfed.

I try to stay on top of the latest in post-apocalypse pop culture, mainly because there has been so little of it in recent years. And when I heard the most popular new YA book series was built around food insecurity, I couldn’t resist. After all, as I’ve written in the journal Nature, “Feeding some 9 billion people by mid-century in the face of a rapidly worsening climate may well be the greatest challenge the human race has ever faced.”

The Hunger Games makes that challenge a literal and hyper-violent one. But like much (though not all) post-apocalyptic fiction, the book spends exceedingly little time actually explaining to anyone how we got into this mess.

Indeed, after reading all three books, I find only one sentence devoted to explaining what caused the apocalypse:

[The mayor] tells of the history of Panem. He lists the disasters, the droughts, the storms, the fires, the encroaching seas that swallowed up so much of the land, the brutal war for what little sustenance remained. The result was Panem, a shining Capitol ringed by thirteen districts … ”

Sounds a lot like global warming, though the books do not flesh out what happened.

Clearly this is the distant future, given that this is the 74th Hunger Games, and some of the technology is well beyond anything we could imagine today.

Somewhat oddly, though, as one fan site explains, protagonist Katniss Everdeen’s home is the “coal mining” district:

Coal Mining — This district is described as being in the area formerly known as Appalachia. The district is also pretty compact compared to some others with a population of just 8,000 people. There is one big clue to where district 12 might be, that we don’t get from reading the book, but from listening to Suzanne Collins read it. She reads Katniss with a southern accent.

Only 8,000 in Appalachia. The 99% ain’t what they used to be. Still, you’d think we’d be off of coal in the 22nd century!

Here’s one fan map:

Okay, well, the underwater parts don’t quite match up to plausible realities, even with melting out all the Earth’s ice and the subsequent 250-foot sea level rise. But hey, this ain’t hard science fiction.

Interestingly, the U.K.’s Telegraph wrote last week that there is a new trend in YA fiction:

The Hunger Games and the teenage craze for dystopian fiction

Wizards and vampires are out. The market in teen fiction is dominated now by societies in breakdown. And it’s girls who are lapping them up.

Many parents might feel worried on finding their teenage children addicted to grim visions of a future in which global warming has made the seas rise, the earth dry up, genetically engineered plants run riot and humans fight over the last available scraps of food. Yet with the arrival of the film of the first book of Suzanne Collins’s best-selling trilogy The Hunger Games this month, dystopia for teenagers has hit an all-time high in public consciousness.

Well, as I’ve said, there is precious little global warming in this book. Not that a book centered around global warming would be easy to make work as fiction, since climate change plays out relatively slowly from a narrative perspective.

In the Telegraph piece, Amanda Craig, “novelist and children’s fiction critic,” works to explain the popularity:

… the new wave of dystopian fiction gives the perfect excuse for why, despite being desperately in love, the protagonists can’t have sex: As Meg Rosoff says, “in a survivalist love affair, you don’t have to worry about having a boyfriend or what clothes you’re wearing, because you’re saving the world.” … Imagining that you’re living in a place in which millions have starved to death (The Hunger Games), been drowned by melting ice-caps (Julie Bertagna’s Exodus), been killed off as surplus because eternal youth has been discovered (Gemma Malley’s The Declaration) or been dried up due to climate change (Moira Young’s Blood Red Road) does tend to make fears about having spots and tests less terrifying. …

Katniss pretends to be in love with her fellow contestant Peeta in order to manipulate the millions watching them on TV. She fights back against the expectations of Panem’s totalitarian regime by pretending to conform. Again, my daughter and her friends find this appealing in an age in which boys’ attitudes to them have been warped by internet pornography.

“Katniss is the kind of strong teenage heroine we were all waiting for,” one put it. “We had Hermione in Harry Potter and Lyra in His Dark Materials as children. If you’ve got a brain, vampires suck.” “Girls aren’t waiting to be saved any more,” Malley says. “They have strong moral compasses, and unlike male protagonists, they have insight into why they are as they are. If you go into schools now, you see teenage girls who are sparky and who think for themselves. Dystopia enables them to have big adventures but it’s also about creating strong characters whom readers care about.”

Warning to parents of tweens: These book are entertaining for sure, with a well-drawn heroine who grows during the course of the books, fights against injustice, and ultimately triumphs. On the other hand, they are hyper-violent, and by the end, Katniss has become a super-jaded and cold-blooded killer. Yes, Katniss has “catness,” the nine lives of the survivor, since she survives more attempts on her life than Jack Bauer or Jason Bourne or James Bond have. But she becomes every bit the killer that the JBs do.

Supposedly the movie will be true to the violence of the books, since they are “co-written and co-produced by Collins herself,” which means they will be quite intense. I’ll let you know.