Call them a couple: The U.S. economy and energy consumption, along with the greenhouse gas emissions they create, have always grown and plunged together. But as the U.S. embraces energy efficiency and renewables, those things aren’t dancing to quite the same beat anymore. In fact, they’re “decoupling,” and could be heading toward a permanent divorce.

New data from the U.S. Department of Energy shows that overall U.S. energy consumption is slowing and is not expected to grow much at all over the next 25 years despite both a growing economy and population. Overall, U.S. energy consumption is expected to grow 0.3 percent annually between now and 2040. That’s half the expected U.S. population growth rate and dramatically less than the projections for U.S. economic growth through 2040 — 2.4 percent. Greenhouse gas emissions from burning energy are expected to grow 0.1 percent in that time.

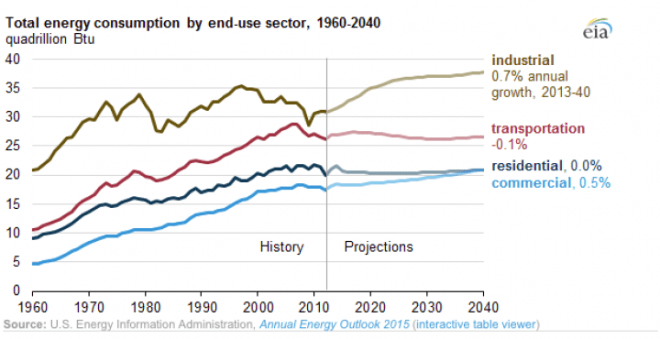

Historic and projected U.S. energy consumption by sector through 2040.EIA

U.S. energy consumption declined when the recession hit, but with big advancements in energy efficiency and growth in renewables, Americans just aren’t burning quite as much energy as they used to even in a growing economy.

“Within a recession, people ask, won’t we resume a growth path? We’re saying we don’t think so — not a decline path, but basically a plateau,” U.S. Energy Information Administration analyst Jim Turnure said.

The details look like this: Thanks to an embrace of energy efficiency, residential energy consumption won’t likely grow at all over the next 25 years. With more Americans driving electric cars and more energy-efficient vehicles, energy use in the transportation sector will decline just slightly as gasoline consumption dives more than 20 percent by 2040. Industrial energy use will grow about 0.7 percent.

That’s good news for the climate because the energy intensity of the economy is declining, which means greenhouse gas emissions are likely to grow at only a fraction of the rate that the economy is expected to grow in the coming years.

Michael Mann, climate researcher and director of the Earth System Science Center at Penn State University, said in March that the U.S. still needs to create a larger gap between greenhouse gas emissions and economic growth.

“I’m hopeful this is the beginning of a trend,” he said, referring to emissions in the U.S. “The fact that countries like Germany have so dramatically lowered their carbon emissions with mechanisms like feed-in tariffs that incentivize non-fossil-fuel energy, and the fact that the West Coast and Northeast states here in the U.S. are investing more in renewable energy, means that we ought to be seeing a decrease in emissions. Now it appears that we are seeing this in the numbers.”

Turnure said this lack of growth in energy use in the U.S. leads to a big question about the future of energy and innovation, to which there is no clear answer.

“We wonder if the slowdown in consumption can affect the pace of investment (in new energy technology markets),” he said. “If nobody needs to get any new energy production, might that slow down the market for new technology and technological improvement?”