Picarro

Although natural gas production emits less CO2 than other fossil fuels, it still spits plenty of junk into the atmosphere. But backers of a new gadget released Monday say they’ve hit on a way to help frackers clean up their act.

Boosters of natural gas often flaunt the stuff as a “clean” fossil fuel, because when it burns — in a power plant, say — it releases far less carbon dioxide than coal or oil. But with the growth of fracking nationwide, some academics and environmentalists have flagged a silent problem that threatens to undermine the purported climate gains of natural gas: “fugitive” methane emissions.

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, even more so than CO2 over the short-term. And natural gas production creates a lot of it: The EPA predicts that methane from the natural gas industry will be one of the top sources of non-CO2 emissions in coming decades. A 2011 federal study [PDF] found that taken all around, the total greenhouse footprint for shale gas could be up to twice that of coal over a 20-year period. The catch is that it doesn’t have to be so bad. Much of that methane is leaking out (hence “fugitive”) unnecessarily from gas wells, pipelines, and storage facilities — so much so that the Environmental Defense Fund calls methane leakage from natural gas operations “the single largest U.S. source of short-term climate-forcing gases.”

But nailing down exactly how much methane leakage there is has proved a bit challenging: Some independent academic studies say up to 9 percent of all the natural gas extracted leaks out, while the official EPA figure is less than 3 percent. Academics, government agencies, and environmental NGOs are at work to shore up this figure, but the effort can be costly and require teams of specialized physicists and chemists.

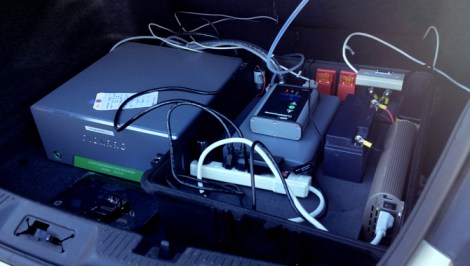

Enter Picarro, a California-based scientific instrument company that Monday released a new gadget the company says will streamline locating leaks and finding out how much methane is streaming out of them. The “Surveyor” attaches to any car, and consists of a computer, an air sampling hose, and a GPS device. Together, says Picarro CEO Michael Woelk, they can sniff out methane and pinpoint the exact spot — like a crack in a pipe — it’s coming from, then feed the data to any web-enabled mobile device in a format understandable without an atmospheric physics PhD. “All we have to do is drive downwind of the source,” Woelk says.

Woelk says his technology has been vetted by NOAA scientists and field-tested with intentionally released control leaks, and already made available to pipeline operators like California’s PG&E. Monday, he pitched it at a conference of fossil fuel developers in Houston and hopes to have it deployed on fracking sites nationwide soon.

This kind of technology “is exactly what we need moving forward,” says EDF Chief Scientist Steve Hamburg. Last year Gina McCarthy, Obama’s new pick to head the EPA, pushed frackers to adopt “green completion” equipment, which can capture smog-causing pollutants escaping from natural gas wells. But there is currently no federal regulation on methane emissions from natural gas operations (Woelk says he would support such regulation; Hamburg declined to comment). Hamburg says better tools to locate and measure methane leaks are needed, but remained skeptical about the reliability of data from equipment, like the Surveyor, that could obviate the need for scientific boots on the ground.

“It needs to be taken out and test-driven,” he says.

In the national fracking debate, unassailable data about environmental impacts is in high demand and short supply; Woelk says his device can be a tool for those drillers who are taking legitimate steps to curb their methane emissions to distinguish themselves from those who aren’t, and also to provide hard data as a baseline if the federal government pursues a cap on methane.

“Transparency is good for the industry,” he says. “If they don’t fix the fugitive leak problem, they won’t be seen as a clean fuel.”

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.