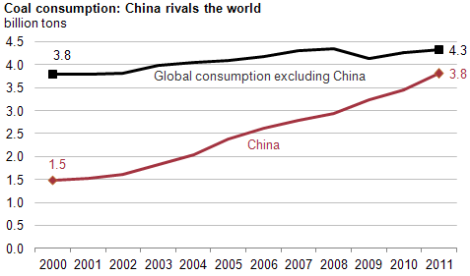

The most worrisome energy trend in the world, by a wide margin, is rising coal consumption in China:

The figures are pretty stunning: Chinese coal demand has been rising at about 9 percent a year for the last 12 years. By comparison, coal demand in the rest of the world has been rising at about 1 percent annually. China now burns almost half the world’s coal.

Cheap coal power has been a boon to China, an engine pulling millions and millions of people out of poverty. But it has also brought nightmarish local pollution problems — which are not remaining local — and it of course threatens to tip the climate into chaos, which will do more damage to the Chinese people, over the long term, than the last decade of growth has done good. It is, as China expert James Fallows says, an “environmental emergency” that threatens to stop China from ever catching up to the developed world.

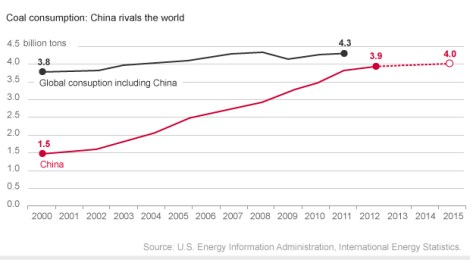

Most projections [PDF] have coal use in China continuing to increase for decades to come. But there are reasons to think those projections overstate demand — that China’s appetite for coal may peak sooner than expected. For one thing, the Chinese government is signaling that the country’s coal consumption will peak by 2015, at 4 billion tonnes.

This would be achieved through a cap on total energy consumption, as part of China’s next five-year plan. It would be, to put it mildly, a remarkable feat, a matter of flatlining energy demand growth almost overnight. If China can pull it off, it will be (comparatively speaking) a blessing for the climate and future generations.

There is, quite rightly, skepticism about the proclamation:

Foreign energy analysts are mostly sceptical that China can meet its “non-binding” energy goal, pointing out that it missed its 2010 target by a large margin.

They are broadly unconvinced that the energy targets can be achieved without an intolerable drop in the GDP growth rate.

Chinese officials and analysts acknowledge that state-owned enterprises, regional leaders and their political patrons have resisted or ignored previous edicts.

(More skepticism, especially from the Australian coal industry, here. More on the inadequacy of China’s efforts to date here.)

I don’t buy the scare story about GDP. Many of China’s most carbon-intensive industries (iron, steel, concrete) are reaching a plateau anyway. But that last bit, about the difficulty of making central-government edicts “stick” in the provinces, is a real concern. It’s difficult to tell exactly what’s going on from the story, but it seems that responsibility for reaching the goal will be apportioned to regions and state-owned companies, so perhaps they will be held more accountable this time. Making sustainability a route to advancement in the party is key to getting it done in China.

Regardless, Chinese government officials are saying they will do “whatever it takes” to hit this target. If nothing else, it signals an increasing political consensus in China that coal-driven growth must be tamed. It will be the drama to watch over the next decade. All our fates hinge on it.