Even as the number of Americans relying on the Colorado River for household water swells to about 40 million, global warming appears to be taking a chunk out of the flows that feed their reservoirs.

Winter storms over the Rocky Mountains provide much of the water that courses down the heavily tapped waterway, which spills through deep gorges of the Southwest and into Mexico.

Low water levels in late 2014 at Lake Powell, which is a Colorado River water reservoir built along the border of Utah and Arizona.Jessica Mercer

But flows in recent decades have been lighter than would have been expected given annual rain and snowfall rates — and a new study has pinpointed rising temperatures as the likely culprit.

“For a given precipitation over the cool season, from October through April, we’re seeing less flow than we’ve seen in the past,” said James Prairie, a researcher with the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s Upper Colorado Regional Office. He was not involved with the new study.

As greenhouse gas pollution piles up in the atmosphere, it’s trapping heat and raising global temperatures, which is beginning to parch the Colorado River watershed. Heavier impacts on drinking water supplies in the West and elsewhere are projected for the future as warming accelerates.

The new research, published in Geophysical Research Letters by academics and a federal scientist, focused on the upper stretches of the river. It attempted to parse out the different roles of temperature, precipitation, and soil moisture on the variability of yearly water flows since reliable record-keeping began in 1906.

Annual Colorado River flows have naturally swung up and down over time, but the natural trends have been bucked in recent years and decades.

“What we’re seeing now is that, consistent with more of the global observations in terms of warming, that it’s not just a fluctuation that’s within that historical back and forth,” Prairie said. “That oscillation is starting to break from that range.”

Temperatures appear to have been playing a larger role in reducing the flows of water down the Colorado River since the late 1980s, the findings from the new study suggested.

“If you look at the trend in temperature over this period, we see a warming trend,” said Connie Woodhouse, a University of Arizona professor who led the new research. “We’re finding in those years temperatures explaining a lot more of the variability.”

Warmer temperatures cause more snow to fall instead as rain, and they cause snowpacks to melt earlier. Both of those effects lengthen growing seasons of riverside vegetation, which allows it to suck up more water as it grows. Higher temperatures also increase evaporation.

The likely effects of climate change on rainfall, snow, and streamflow in the West remain difficult to assess, though they’re expected to lead to more rain and less snow, reducing the water volume of the snowpack that melts slowly to fill up the rivers. Storms may also shift southward.

Recent assessments suggest that even without changes to precipitation, the flow through “most of the Colorado River” would “shift to moderately lower” levels as the planet continues to warm, said Andy Wood, a National Center for Atmospheric Research scientist who was not involved with the study.

Although more research is needed, the new study indicates that climate change has been worsening the effects of the recent Western drought on some of the country’s biggest reservoirs.

“The paper is intriguing, but it also leaves open a number of questions that I would think probably need to be addressed by a more detailed analysis,” Wood said.

Worldwide surface temperatures have warmed by about 1 degree C (1.8 degrees F) since the 1800s, worsening heatwaves and droughts. Last year easily broke a global temperature record that had been set one year prior.

Based on computer modeling, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in 2012 warned that each 1 degree C of global warming could increase the amount of water that gets evaporated and sucked up by plants from the Colorado River by 2 to 3 percent. One of the models used suggested the effects would be twice as severe as that.

With 4.5 million acres of farmland irrigated using Colorado River water, and with nearly 40 million residents of seven U.S. states from cities as far afield as San Diego depending on it for municipal supplies, those incremental losses can have a heavy impact — particularly during times of drought.

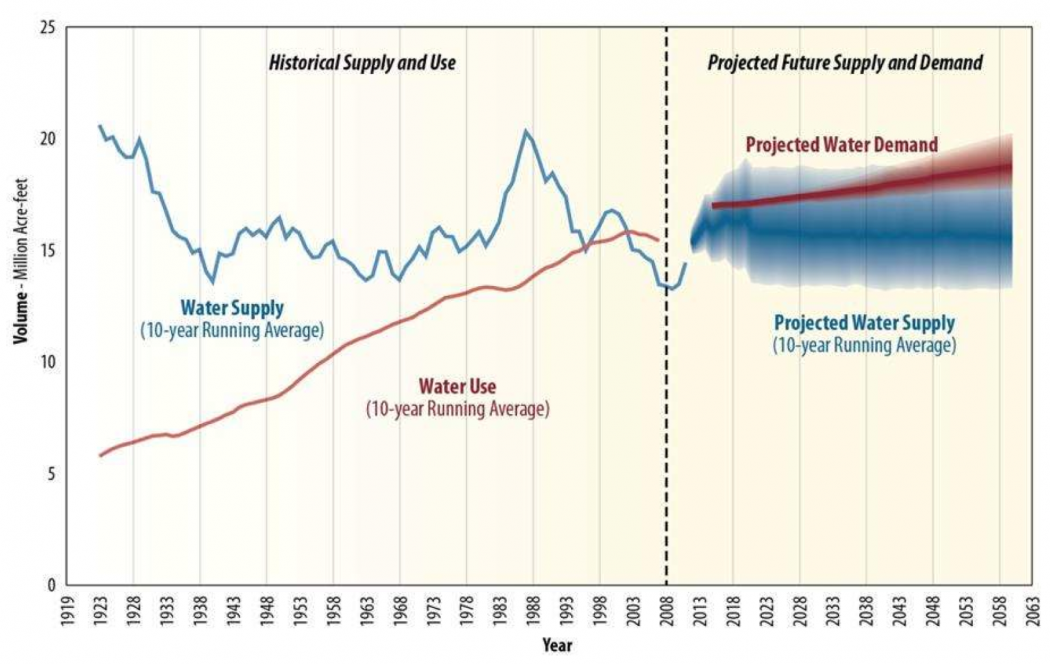

Until the 1990s, yearly supplies of available Colorado River water outpaced demand. Now, the opposite is true.

Demand for Colorado River water has begun outstripping supply.U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

Much of the West has endured drought in recent years, with Lake Powell and Lake Mead — both large reservoirs storing freshwater and producing hydropower in the Colorados River’s downstream stretches — falling to ominously low levels.

Colorado River water shortfalls during the past decade have fueled a rapid and unsustainable frenzy of drilling for groundwater from beneath the watershed.

The Reclamation Bureau officials said the heaviest impacts of higher temperatures are being felt at smaller reservoirs that are relied on by farmers further upstream. Agriculture accounts for about 70 percent of Colorado River water use.

Because those upstream reservoirs are smaller, they’re less capable of storing enough water following wet years to buffer the effects of dry ones.

“Less water in the reservoirs means less water for people who actually want and need the water,” said Peter Soeth, a spokesperson for the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The effects aren’t just being felt by farmers and other water customers, Soeth said. They’re also impacting electrical grids, with less water flow meaning less hydropower.