Warm ocean waters that sucked the color and vigor from sweeping stretches of the world’s greatest expanse of corals last month were driven by climate change, according to a new analysis by scientists, who are warning of worse impacts ahead.

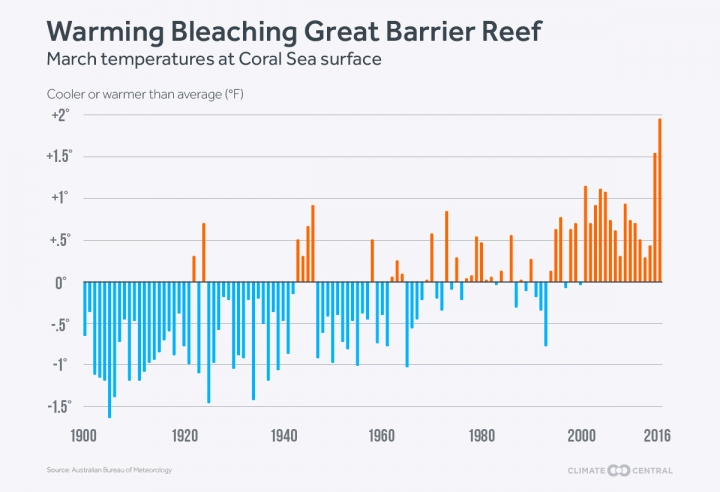

Climate change made it 175 times more likely that the surface waters of the Coral Sea, which off the Queensland coastline is home to Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, would reach the record-breaking temperatures last month that bleached reefs, modeling analysis showed.

The scientists found March Coral Sea temperatures are likely to be 1.8 degrees F (1 degrees C) warmer now than before humans polluted the atmosphere. Temperatures recorded by the Australian government last month were slightly higher than that, in part because of a fierce El Niño.

“We’ve had evidence before” that “human-induced climate change is behind the increase in severity and frequency of bleaching events,” said David Kline, a Scripps Institution of Oceanography coral reef scientist who wasn’t involved with the new analysis. “But this is the smoking gun.”

The new findings suggest similar temperatures will become commonplace by the 2030s, potentially destroying the reef and the tourism and fishing industries that rely on it. The reef’s tourism sector employs 64,000 people.

“There may still be corals, but it’ll look like a very sad reef,” Kline said. “There will probably be a few weedy species that can handle these nasty conditions, but we’ll lose a lot of the biodiversity.”

The warm Coral Sea waters have fueled the worst mass coral bleaching ever recorded on the World Heritage-listed reefs, which are withering from warming and acidifying waters, coral-eating pests, and agricultural pollution.

Climate Central

Bleaching occurs when warm waters cause the colorful algae that provide food for corals to release chemicals that are toxic to their hosts, and they are spat out. Corals, which are rigid animals that shelter rich ecosystems, can recover from bleaching. But persistent high temperatures, overfishing, and other environmental stresses make it more likely they will starve and die.

“As the seas warm because of our effect on the climate, bleaching events in the Great Barrier Reef and other areas within the Coral Sea are likely to become more frequent and more devastating,” the team of Australian university scientists wrote Thursday in The Conversation, announcing the results of the analysis.

Following global average temperature records set in 2014, 2015, January, February, and March, coral reefs from Florida to India have been devastated by the third mass global bleaching event recorded. The first occurred in the late 1990s, leaving one out of six of the world’s corals dead.

Recent surveys showed 93 percent of the Great Barrier Reef afflicted by bleaching, with the impacts worst in the reef’s more pristine northern reaches.

[protected-iframe id=”ae955f21cc3cd3367d381f6d264e4ff9-5104299-94886244″ info=”https://www.facebook.com/plugins/video.php?href=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.facebook.com%2Fclimatecentral%2Fvideos%2Fvb.57984115023%2F10156746453050024%2F%3Ftype%3D3&show_text=0&width=660″ ]

Although the surface temperatures in March were unprecedented, they could become normal within 20 years, the scientists discovered.

The researchers ran Earth model simulations in which greenhouse gases were kept at natural levels. They compared those simulated Coral Sea temperatures with those in modeling runs where climate-changing pollution increased at current rapid rates.

“The human effect on the region through climate change is clear and it is strengthening,” the scientists wrote. “Surface temperatures like those in March 2016 would be extremely unlikely to occur in a world without humans.”

The analysis was produced using established modeling techniques but it wasn’t peer-reviewed before the results were announced Thursday on The Conversation, which is a nonprofit news site founded in Australia that frequently publishes articles written by scientists.

“Because this is happening now, we wanted to do this quickly and get it in the public sphere,” said Andrew King, one of two University of Melbourne researchers who worked on the analysis. University of Queensland and University of New South Wales researchers also contributed. “We will write up a paper after this.”

By the 2030s, the modeling showed this year’s coral bleaching temperatures could become average and after that they may start to seem cool.

“These kinds of temperatures in the future will become normal,” King said. “They’re high for the current period, but by the 2030s it’s going to be about average.”