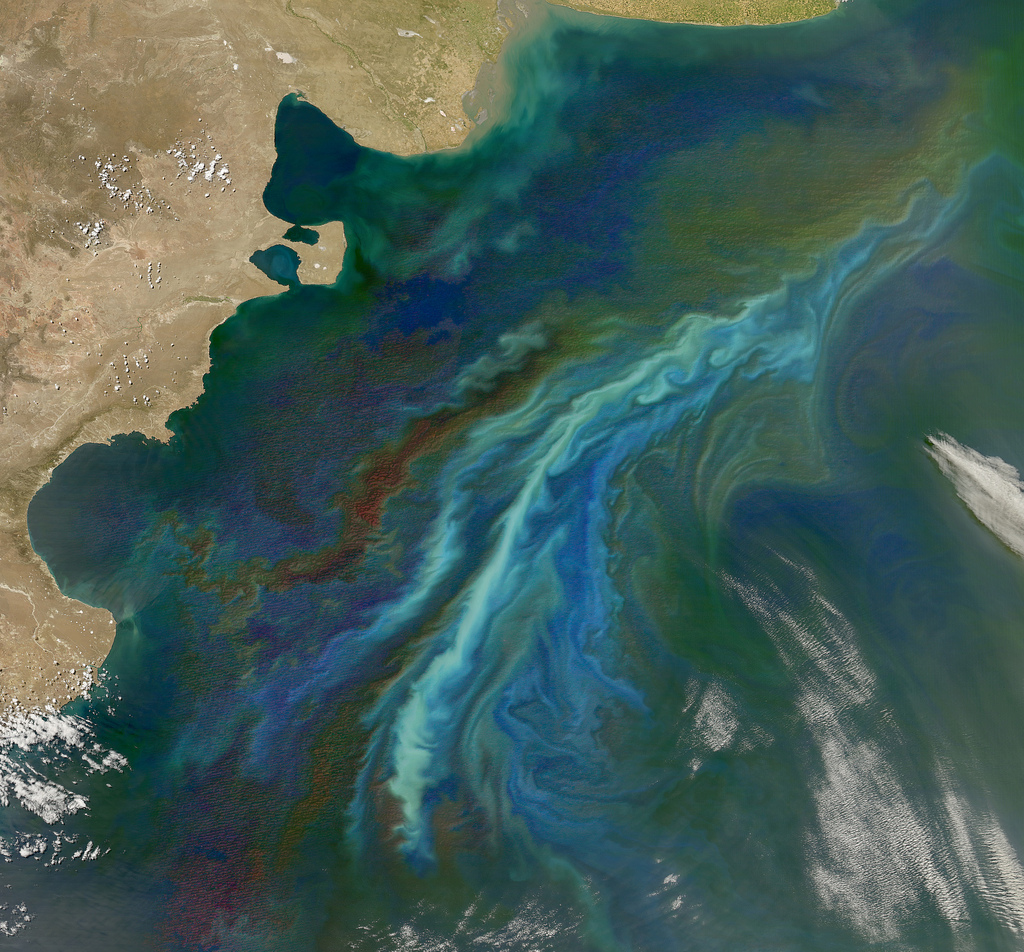

NASA GoddardA plankton bloom off Patagonia. Climate change brings spring and all the events that come with it — like breeding and plankton blooms — earlier than normal.

Rising ocean temperatures are rearranging the biological makeup of our oceans, pushing species towards the poles by 4.4 miles every year, as they chase the climates they can survive in, according to new research.

The study, conducted by a working group of scientists from 17 different institutions, gathered data from seven different countries and found the warming oceans are causing marine species to alter their breeding, feeding, and migration patterns.

Surprisingly, land species are shifting at a rate of less than 0.6 miles a year in comparison, even though land surface temperatures are rising at a much faster rate than those in the ocean.

“In general, the air is warming faster than the ocean because the air has greater capacity to absorb temperature. So we expected to see more rapid response on land than in the ocean. But we sort of found the inverse,” said study researcher Christopher Brown, post-doctoral research fellow at the University of Queensland’s Global Change Institute.

Brown said this may be because marine animals are able to move vast distances, or it could be because it’s easier to escape changing temperatures on land where there are hills and valleys, rather than on a flat ocean surface.

The team looked at a wide variety of species, from plankton and ocean plants to predators such as seals, seabirds, and big fish.

“One of the unique things about this study is that we’ve looked at everything,” said Brown.

“We covered every link in the food chain and we found there were changes in marine life that were consistent with climate change across all the world’s oceans and across all those different links in the food chain.”

The warming oceans are shortening winter and bringing on spring and all the events that come with it — like breeding events and plankton blooms — earlier than normal.

For the species that can’t keep moving towards the colder waters, this could have dire consequences.

“Some species like barnacles and lots of shellfish are constrained to living on the coast, so in places like Tasmania, if they’re already at the edge of the range there’s nowhere for them to go. You could potentially lose those,” said Brown.

The scientists found that 81 percent of the study’s observations supported the hypothesis that climate change was behind the changes seen.

To combat this, Brown said people have to think about changing activities to adapt.

“For example, fisheries might need to move their ports to keep track of the species they prefer to catch,” he said.

“The obvious one is to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions which will slow or reduce the rate of warming in the oceans, but there’s a long lag time in that. Even if we reduce emissions now then those effects won’t be seen for 20 years or so.”

This story first appeared on the Guardian website as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story first appeared on the Guardian website as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.