For many years, the U.S. National Science Foundation, more recently with the help of the General Social Survey, has asked the public the same true or false question about evolution: “Human beings, as we know them today, developed from earlier species of animals.” And for many years, the responses to this question have been dismal. In 2006, 2008, and 2010, for instance, less than half of the public correctly answered “true.”

In 2012, however, the NSF and GSS conducted an experiment to try to better understand why people fare so badly on this evolution question. For half of survey respondents, the words “according to the theory of evolution” were added to the beginning of the statement above. And while only 48 percent gave the correct answer to the unaltered question, an impressive 72 percent correctly answered the new, prefaced version.

So why such a huge gap? Perhaps the original question wasn’t tapping into scientific knowledge at all; rather, it was challenging the religious identity of creationists who think the earth is less than 10,000 years old. Presented with the new phrasing, however, even many creationists know what the theory of evolution states; they just deny that it is true. So are these people really “scientifically illiterate,” as many in the science world might claim, or are they instead … something else?

This is a vital question in the field of science communication, because at its core is the issue of whether we are dealing with mass public scientific illiteracy on the one hand (which presumably could be fixed by education), or with something much deeper and more intractable. What’s more, this problem isn’t confined to evolution. The issue of climate change may be very similar in this respect. Ask a polling question about climate change in one way, and you may cause conservatives to reassert their ideological identities, and reject the most important finding of climate science (that humans are causing global warming). But ask it in another way and, well, it may turn out that they know what the science says after all (even if they don’t personally believe it).

BDEnglerDan Kahan.

Such is the finding of a new paper by Yale law professor and communication researcher Dan Kahan, recently profiled in depth by Ezra Klein in a much read Vox article aptly titled “How politics makes us stupid.” Kahan is becoming widely known for his research showing that political ideology interferes with our most basic reasoning abilities; even our math skills, it seems, go right out the window when political passions come into play. In this new paper, though, Kahan isn’t showing how dumb we are. Rather, he’s doing the opposite: Showing that if you ask the questions the right way, Americans know a lot more about climate science than you might think. (Even conservatives.)

“Whether people ‘believe in’ climate change, like whether they ‘believe in’ evolution, expresses who they are,” writes Kahan.

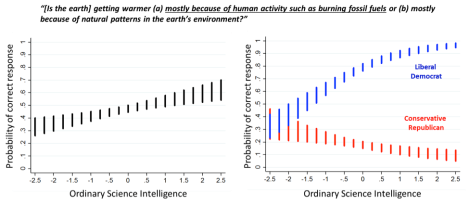

To understand Kahan’s analysis, it helps to start where much of his prior research — extensively covered by Klein, myself, and others — left off. Kahan has defined a measure that he calls “ordinary science intelligence,” which assesses how good people are at mathematical and scientific reasoning and at questioning their own beliefs. Using this survey tool, he is able to present evidence showing that (1) as people get better at science, they are more likely in general to affirm that global warming is mostly due to human activities; but (2) as soon as you split people up in to liberals and conservatives, that conclusion goes out the window. Actually, liberals get way better in their answers as their science ability increases, and conservatives get considerably worse:

Probability of giving the correct answer on a question about climate change in relation to individuals’ political ideology and science “intelligence.” Click to embiggen.

This “smart idiot” effect has prompted a ton of hand-wringing on the left; by now, Kahan has captured it in many studies. In the context of the current research, though, he’s just getting started.

Mirroring the NSF’s approach to evolution, Kahan created a new questionnaire that he hopes can more extensively measure people’s knowledge about the science of climate change. But — crucially — in this questionnaire, most of the questions started out with the phrase “climate scientists believe that …” Such is Kahan’s attempt (only an initial one, he stresses) to disentangle people’s identities and political ideology from what they just plain know.

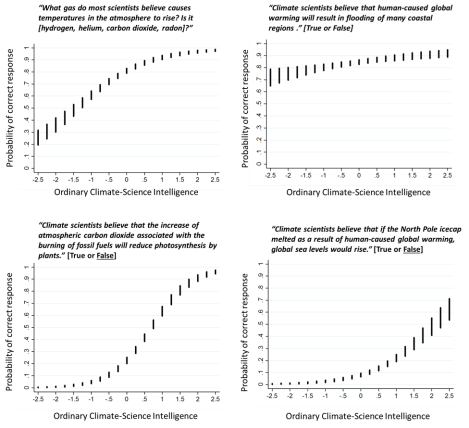

Here are some of the questionnaire items, and how members of the public tended to fare on them, plotted in relation to how climate science literate they were:

Dan KahanExamples of “Ordinary Climate Science Intelligence” items and the public’s probability of giving the right answers. Answers (from left to right, top to bottom) are “carbon dioxide,” “true,” “false,” and “false.” Click to embiggen.

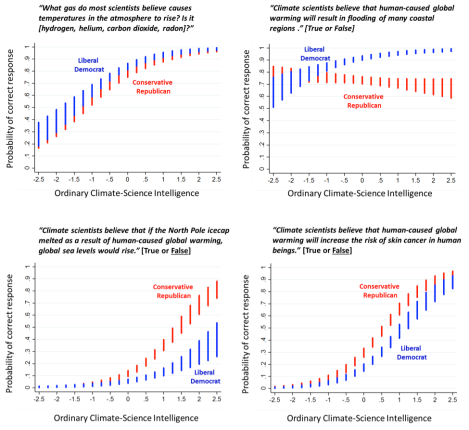

Next, Kahan examined the patterns of responses based on ideology. This time, though, he no longer saw a performance split between those on the left and those on the right. Nor did he see a uniform pattern in which liberals tended to be more correct with higher levels of intelligence or science literacy, even as conservatives were more incorrect. Rather, sometimes the two groups were nearly the same in their performance, and sometimes one group did a little better or a little worse than the other:

Dan KahanLeft right differences in responses to climate science “intelligence” questions. Correct answers (from left to right, top to bottom) are “carbon dioxide,” “true,” “false,” and “false.” Click to embiggen.

Granted, there is an argument to be made that part of this depends on the nature of the questions. Kahan threw in a number of trick questions, including one that almost everybody got wrong: “Climate scientists believe that if the North Pole icecap melted as a result of human-caused global warming, global sea levels would rise.” That’s true of the South Pole, because the vast Antarctic Ice Sheet sits atop a landmass. It’s also true of Greenland. But it’s not true of the North Pole, where the ice cap is comprised of floating sea ice, whose melting won’t raise sea levels any more than the melting of ice cubes on a summer day causes your glass of water to overflow.

There was another noteworthy pattern in question responses. Whenever Kahan posed a question about a risk of global warming that turned out not to be real — for instance, “Climate scientists believe that human-caused global warming will increase the risk of skin cancer in human beings” — he tended to trick liberals a bit more than conservatives. But that’s simply because liberals were more inclined to believe bad things about climate change, and conservatives to dismiss them.

In any event, Kahan concludes, on the basis of these results, that the public basically does understand climate science, on both sides of the aisle. “Everyone has gotten the memo on what ‘climate scientists believe,'” he writes. It’s just that there are certain questions, and certain ways of phrasing them, that lead conservatives to trumpet their political identities, rather than express their knowledge, in response to survey questions. Or as Kahan writes:

The problem is not that members of the public do not know enough, either about climate science or the weight of scientific opinion, to contribute intelligently as citizens to the challenges posed by climate change. It’s that the questions posed to them by those communicating information on global warming in the political realm have nothing to do with — are not measuring — what ordinary citizens know.

Conservatives will probably be elated by these findings. But for others, Kahan’s conclusions are likely to be quite controversial, especially since he packages them alongside a critique of a leading strategy to communicate the reality of climate change, namely, by emphasizing that 97 percent of scientists agree that humans are causing global warming. Kahan thinks that’s a way of pushing conservatives’ political identity buttons, rather than tapping into their knowledge. (For a rebuttal to Kahan’s criticisms from John Cook, one of the authors of the original study demonstrating that 97 percent of published papers — that take a stance on the matter — accept the scientific consensus on climate change, see here.)

Still, those who wish to communicate to the public about climate change will have to grapple with Kahan’s assertion that conservatives really aren’t ignorant about the issue — they’re just highly prone to defend their worldviews when asked certain kinds of questions. If Kahan is right, the implication is that we need to talk about climate science in a way that is entirely devoid of cultural meanings that will antagonize the right.

Later in the paper, Kahan goes on to assert that precisely this strategy is working right now in Southeast Florida, where members of the Regional Climate Change Compact have brought on board politically diverse constituencies by studiously avoiding pushing anyone’s buttons. Kahan even shows polling data suggesting that questions like “local and state officials should be involved in identifying steps that local communities can take to reduce the risk posed by rising sea levels” do not provoke a polarized response in this region. Rather, liberals and conservatives alike in Southeast Florida agree with such a statement, which references a major consequence of climate change while ignoring the gigantic elephant in the room … its cause.

Here’s the problem, though. Maybe this approach will work up to a point, or in certain locales (in North Carolina, the response to sea level rise is pretty different). But at some point, we really do need to all agree that the globe is warming, so that we can then make very difficult choices on how to deal with that. To save our feverish planet, it is dubious that merely having conservatives know what scientists think — rather than accepting it themselves, taking the reality into their hearts and identities — will be enough.

On a previous episode of the Inquiring Minds podcast, Dan Kahan debated psychologist Stephan Lewandowsky about how to communicate the science of climate change:

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.