You probably know Monsanto as the world’s leading producer of genetically engineered seeds — a global agribusiness giant whose critics accuse it of everything from boosting our reliance on pesticides to driving Indian farmers to suicide.

But that’s actually just the latest in a long series of evolving corporate identities. When the company was founded in 1901 by a St. Louis pharmacist, its initial product was artificial sweetener. Over the next few decades Monsanto expanded into industrial chemicals, releasing its first agricultural herbicide, 2,4-D, in 1945. In the ’50s, it produced laundry detergent, the infamous insecticide DDT, and chemical components for nuclear bombs. In the ’60s, it churned out Agent Orange for the Vietnam War. In the ’70s, it became one of the largest producers of LED lights.

It was around this time that Robb Fraley, now Monsanto’s chief technology officer, joined the company as a mid-level biotechnology scientist. Back then, he recalls, the company had its hand in oil wells, plastics, carpets — you name it. It wasn’t until the early ’80s that Monsanto began to shift its focus to biotechnology, conducting the first U.S. field trials of bioengineered plants in 1987. By the end of the ’90s, it was a full-fledged biotech company. And over the last 10 years, after a series of seed company acquisitions, it has become the company we all know and love — or hate — today.

Now, there’s a new evolution on the horizon: “I could easily see us in the next five or 10 years being an information technology company,” says Fraley.

That’s right: Monsanto is making a big move into big data. At stake is an opportunity to adapt to climate change by using computer science alongside the controversial genetic science that has been the company’s signature for a generation. Data stands to benefit Monsanto’s bottom line, too: In its 2013 annual report, the company blamed lost profits on knowledge gaps about both the climate and its customers’ farming practices. And information services could even help Monsanto get its foot (and its seeds) in the door of untapped global markets from Africa to South America.

Seeds of a data company

Whatever your feelings about Monsanto, it’s hard to argue that the company isn’t paying attention to climate change. When I met Fraley in New York in September, he explained that since he joined the company in 1981, Monsanto scientists have observed corn production belts migrate northward by about 200 miles. That means traditional strongholds like Kansas are becoming less productive, while new markets for Monsanto products are opening in places like North Dakota and southern Canada. But for Fraley, who has spent his career digging through the minutiae of microscopic nucleotides, the most interesting trends are emerging on a much smaller scale.

“Just a couple degrees difference changes when insects will hatch, or when diseases will break out,” he says. “So that puts a real premium on modeling microclimatic conditions, so you can become predictive on not only which field, but which part of a field should someone be looking at.”

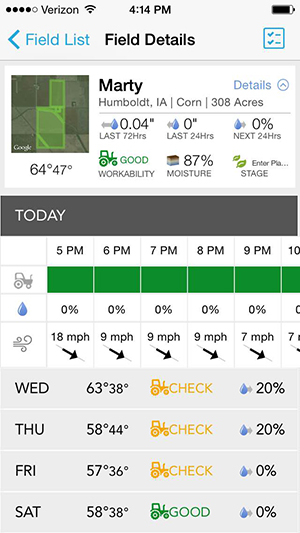

A screenshot of the Climate Basic app from my iPhone in October shows conditions on my family’s farm in Iowa.

Last year, Monsanto made a major investment in big data analytics when it paid $930 million to acquire Climate Corporation, a San Francisco tech firm whose original business was selling crop insurance to farmers with rates set by some of the most detailed weather data available anywhere. These days, Climate Corp’s flagship product is a smartphone app called Climate Basic. The screenshot to the left — from my iPhone, taken back in early October — shows my family’s corn and soy farm in Iowa. You can see each of five individual fields highlighted. There are 30 million agricultural fields in America, and the app has all of them, mapped with soil and climate data to a 10-meter-by-10-meter resolution.

The app knows our fields’ real-time temperature, weather, and soil moisture, and what we can expect on those metrics for the coming week. The green tractor tells me Saturday is the best day to work the fields. If I were to input data about what kinds of seeds I planted and when, it could tell me when to harvest them and how much yield to expect. A premium, paid version of the app includes other detailed recommendations — for example, how much water and fertilizer to use.

That advice, says Climate Corp. CEO Dave Friedberg, represents a fundamental shift “from intuition-based decision-making to analytical decision-making,” combining real-time climate data with records from Monsanto’s trove of field trials.

“Ultimately all of this is the digitization of physical phenomena, and using that to better predict the future,” he says.

Sprawling databases have long been an essential item in the Monsanto toolkit. Locating the genes for favorable traits in plants — drought or insect resistance, for instance — so they can be bred into new seed varieties requires sifting through the billions of base pairs in a genome, which is one reason why biotechnology has grown in tandem with computer processing power over the last two decades. Since the ’80s, Monsanto has amassed one of the world’s largest agricultural databases, gleaned from the results of countless field tests of countless seed varieties under countless experimental conditions. That’s what made Climate Corp. such an attractive investment: The opportunity to integrate that company’s climate database with Monsanto’s seed data.

With Monsanto now at the helm, a team of a dozen Climate Corp. researchers are working full-time to pull climate data from government satellites and weather stations, university research sensors, and any other source they can find. This gets fed through a pipeline of data analysts and software engineers and emerges at the other end as Climate Basic.

The payoff for growers can be huge: Monsanto estimates that farmers typically makes 40 key choices in the course of a growing season—what seed to plant, when to plant it, and so on. For each decision, there’s an opportunity to save money on “inputs”: water, fuel, seeds, custom chemical treatments, etc. Those savings can come with a parallel environmental benefit (less pollution from fertilizer and insecticides). These decisions can also help farmers make money by squeezing more yield from the same acreage. This year, as my colleague Tom Philpott reported, high input costs and low commodity crop prices have led Midwestern farmers to lose $225 per acre of corn and $100 per acre of soybeans. Big data, Friedberg says, reveals how seemingly small choices — a four- or five-day difference in planting time, for instance — can have a significant impact on the final harvest and on farmers’ bottom lines.

A new tool for climate adaptation

Precision agriculture is also an essential climate adaptation strategy. Monsanto’s data tools could become invaluable for farmers struggling to cope with changing conditions, says Rebecca Shaw, a scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund who studies the link between agriculture and ecosystems. With less water available, “we can’t afford to be wasteful,” she says. “It’s really important that we get better at understanding what the crop needs and when, and apply only that.”

The promise of data-driven farming, Shaw says, is to streamline the whole process and get the same or better output while cutting back on inputs.

Of course, data is a two-way street: Every new user of Climate Corp. software is a new source of real-time information for Monsanto about its customers — what kinds of products they’re using and how much they’re producing (i.e., how much money they’re making). Matt Erickson, an economist with the American Farm Bureau Federation, says farmers need to proceed with caution when they sign on to share proprietary data about their business operations with an outside party like Monsanto. The key, Erickson says, is for farmers and Monsanto to be on the same page when it comes to deciding if and how that data will be shared with third parties — other retailers, for example, or crop insurance companies. It’s just like how we all want to be kept apprised of the ways Google or Facebook use our data.

“The big thing we’re striving for is transparency,” Erickson says. “Making sure farmers are aware of any secondary or tertiary uses.”

Climate Corp.’s privacy policy dictates that farmers continue to own their data after it is shared, and that data won’t be used for purposes not explicitly approved by the farmer. Still, Fraley says he envisions using data to market custom products and services to farmers; a farmer whose crops are suffering from a disease or insect infestation might get an ad for appropriate chemical treatments, for example.

“There’s a huge opportunity on the marketing side,” he says. “We’re just exploring it.”

Privacy concerns aside, American farmers seem to be buying in. According to Friedberg, prior to the Monsanto acquisition, less than 10 million of the 161 million acres of U.S. farmland were being farmed with help from Climate Corp. software. Today, that number has grown to over 60 million. In other words, more than a third of U.S. farmland is now cultivated with the guidance of Monsanto climate data. And it’s continuing to grow rapidly: According to Climate Corp., the number of Climate Basic accounts has grown from 30,000 to over 70,000 just since the spring of this year.

“The information itself becomes the business”

For Monsanto’s data push, the U.S. market is only the beginning.

Efforts to increase crop yields are especially important in the developing world. The global population is projected to swell to more than 9 billion people by 2050 — with over half of that growth in Africa. The U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that as a result, food production will have to increase by 70 percent. But according to the U.N.’s latest climate change report, South Asia and sub-Saharan African — the two regions with the most food insecurity — are actually expected to see an 8 percent drop in crop yields by 2050, thanks to rising temperatures and increasingly sporadic rainfall.

Fraley estimates that in central Africa, a typical corn farm produces less than a 10th of what the same-sized plot would yield in the U.S., despite having roughly equivalent soil and weather quality. Poorly bred seeds are part of the problem, he says, but biotechnology can’t fill the gap by itself. That’s because African countries also suffer from a chronic lack of basic weather data that U.S. farmers take for granted. Sub-Saharan Africa (excluding South Africa) has roughly one weather station per 239,000 square miles; the U.S. has one station per 14,000 square miles.

The need for better data is becoming even greater as climate change alters rainfall patterns that have informed farming practices for generations. A 2012 U.N. study found, for example, that between the 1970s and the 2000s, precipitation during Tanzania’s main rainy season fell by nearly 30 percent. The rainy season now starts a month earlier, as well.

What farmers in the developing world do have, though, is cellphones. And that’s where Monsanto sees an opportunity to distribute its data. “There will be value in information on crops and geographies where we currently don’t do business, so it’s a great opportunity to expand our footprint and get us into new spaces,” Fraley says. “Where the information itself becomes the business, we see a lot of opportunity.”

Beyond weather predictions, mobile data services could help African farmers identify pests and diseases — text in a photo of a mysterious bug, and get advice on how to get rid of it. They could also help connect farmers in remote villages to urban markets for their crops, says Andrew Mattick, a former World Bank agricultural consultant who is currently based in Mozambique. Rural farmers are often so isolated from markets, he says, that it’s impossible to know whether they are getting a fair price for their produce.

“When you’re not linked to markets,” he says, “you have no idea how much a cabbage costs in Maputo [the capital].” Mobile data could help bridge that gap.

Monsanto is already active with data services in India, where according to Friedberg some 3 million smallholder farmers have signed up for text message updates that are essentially a simplified version of the Climate Basic app. Field-by-field mapping efforts are underway in South America, Fraley told me, and SMS services are being developed for Africa, where the company’s reach is currently relatively small.

Data tools “are going to transform agriculture for smallholders across Africa,” Fraley says. “Even farmers who cannot read or write can intuitively digest the information on a cellphone.”

Of course, data products are only part of the business model. There are strict limitations on GMO crops in India and in all but four African nations, as Michael Specter recently reported in The New Yorker. But Fraley envisions that as African farmers begin to share data about their farms, the company “will initially use that approach to support our seed business. There’s a huge opportunity to provide African growers with better seeds.”

In other words, free data services provided in Africa could eventually feed back information about growing practices, disease and insect problems, and climate conditions. That information could be converted into seeds developed specifically for African fields and sold to African farmers. The ball is already rolling: In May, the company announced the results of the first harvest in Kenya of a new variety of drought-resistant corn that had been in the works since 2008. Yields from the new seeds were twice the national average, the company reported.

The real test for Monsanto’s data push will be closer to home. For farmers who have already signed on to the company’s services, the next few years’ worth of harvests will show whether a smartphone app really can pull extra corn from their ground — and put extra cash in their pockets. Friedberg is confident that it will.

“As you start to realize that the upside is there,” he says, “everything starts to change.”

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

This story was produced as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.