Sweating in the hot sun, the protesters sat in wooden canoes, staring up at a 40-foot-tall freight carrier. The gigantic vessel was trying to leave the Port of Newcastle in Australia, the largest coal port in the world. The canoers rowed and chanted and did their best to block this boat and others from leaving the harbor, until the police intervened.

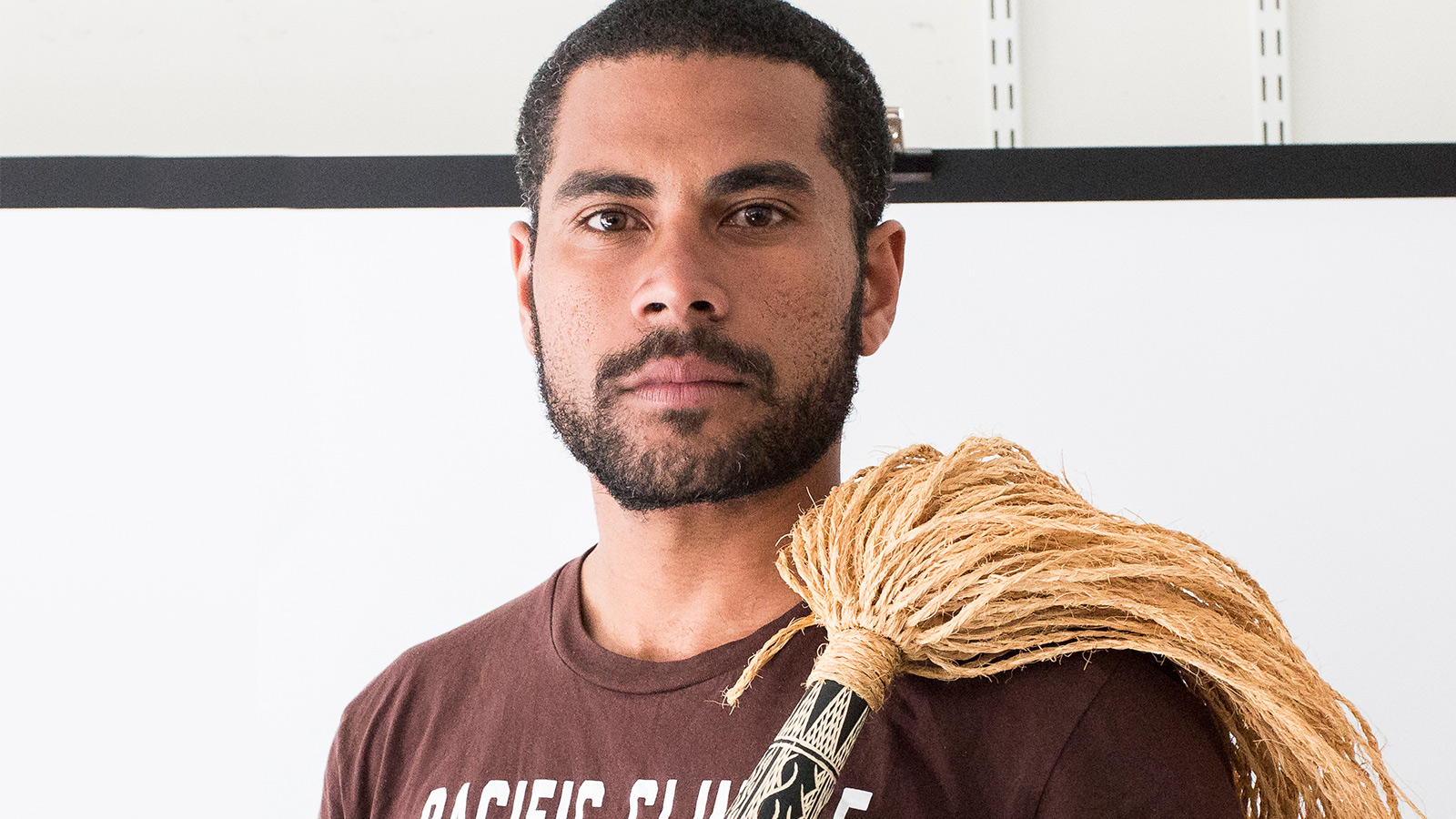

Back on the shore, Fenton Lutunatabua captured every moment on his smartphone. It was late 2014, and Lutunatabua had organized the protest with a group called the Pacific Climate Warriors, an alliance of activists from Vanuatu, Tokelau, the Solomon Islands, the Marshall Islands, and eight other island nations in the South Pacific. The demonstration was a not-so-subtle attack on the coal industry.

Having grown up in Fiji, Lutunatabua is acutely aware of the ways the fossil fuel industry and carbon emissions threaten his part of the world. The Pacific Islands, a region broadly encompassing some 25 nations (more conventionally considered the groupings of Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia) and more than 25,000 islands, face profound threats from sea-level rise and severe weather incidents. Salt-water inundation has already threatened crop land and contaminated drinking water. Lutunatabua has responded by harnessing a tool relatively new to his home: social media.

Lutunatabua tweeted, Instagrammed, Flickred, and blogged the 2014 event in real time. Pretty soon, the unfiltered voices of the Pacific Climate Warriors rocketed to the internet and grabbed headlines around the world.

“Growing up, we were always reminded of our connection to the land and ocean, that was our truth,” he told Grist, remembering his summers spent fishing and snorkeling. “The continued expansion of the fossil fuel industry means the direct export of destruction to the Pacific Islands.”

After studying journalism and social psychology at the University of the South Pacific, in Fiji, the 29-year-old realized there was a gap in the way information was delivered. As recently as 15 years ago, most news in the region came by way of transistor radios. This meant that only one voice — that of a talk show host or news anchor — reached listeners. But an overhaul of the telecommunications industry has helped bring internet and cell phones to the masses. In 2006, just 10 percent of Pacific Islanders had access to a cell phone. By 2012, that number jumped to 60 percent. Data collected by GSMA Intelligence, a group that conducts research on mobile operator statistics, projects that there will be 5.1 million mobile subscribers in the Pacific Islands by 2020.

The explosion in cell phones has also brought instant, portable access to Facebook, one of Lutunatabua’s most effective tools for spreading information. Through both his personal Facebook page and the page for 350 Pacific, where he now works as an activist and communications coordinator, Lutunatabua shares news articles, behind-the-scenes images, and interviews with activists from the Pacific Islands (editor’s note: 350.org’s founder, Bill McKibben, is on Grist’s board). He’s increasingly using Instagram and Twitter, too, to document protests and push for climate action.

https://www.instagram.com/p/uPHnNfmz1W/?taken-by=350pacific&hl=en

Social media is also an important tool for Lutunatabua and others to disperse first-responder information about natural disasters. During last year’s Cyclone Pam, a member of the Pacific Climate Warriors from Vanuatu sent Lutunatabua photos and footage of the storm. Lutunatabua quickly shared the images on the 350 Pacific Facebook page, and in the process gave the internet early glimpses of what became one of the most intense tropical cyclones in the southern hemisphere. Now, live-tweeting storms is just another part of the job.

This is currently happening in Lami.Power's out& I can hear tree's falling in the distance. #TCWinston #PrayForFiji pic.twitter.com/HJiEJD7Xy8

— 350 Pacific (@350Pacific) February 20, 2016

The next tool Lutunatabua wants to master: Snapchat.

“Snapchat is real life, showing how things look without a filter,” he said. Internet data in the Pacific Islands can be prohibitively expensive. The shorter the video, the more likely it will be viewed. “People are way more likely to watch a 10-second snap. And it’s from your point of view, you can show the world what’s really happening.”

Lutunatabua hopes all of this exposure will help change the conventional Western perception that people impacted by climate change are “victims” or “refugees.” For Lutunatabua and other locals, such terms suggest a helpless people, a community standing knee-deep in the rising tide, waiting to be engulfed.

“The whole reason we exist is to change the narrative, to show that we are not mere victims of climate change, and that we’re not ready to flee our countries,” Lutunatabua said. “We really want to fight, we want to hold people accountable. Most of all, using the voices of people at the front lines of climate change, we want to build the anti-narrative.”