As the remnants of what was once Hurricane Harvey move mercifully away from Texas, forecasters are already eyeing another monster storm.

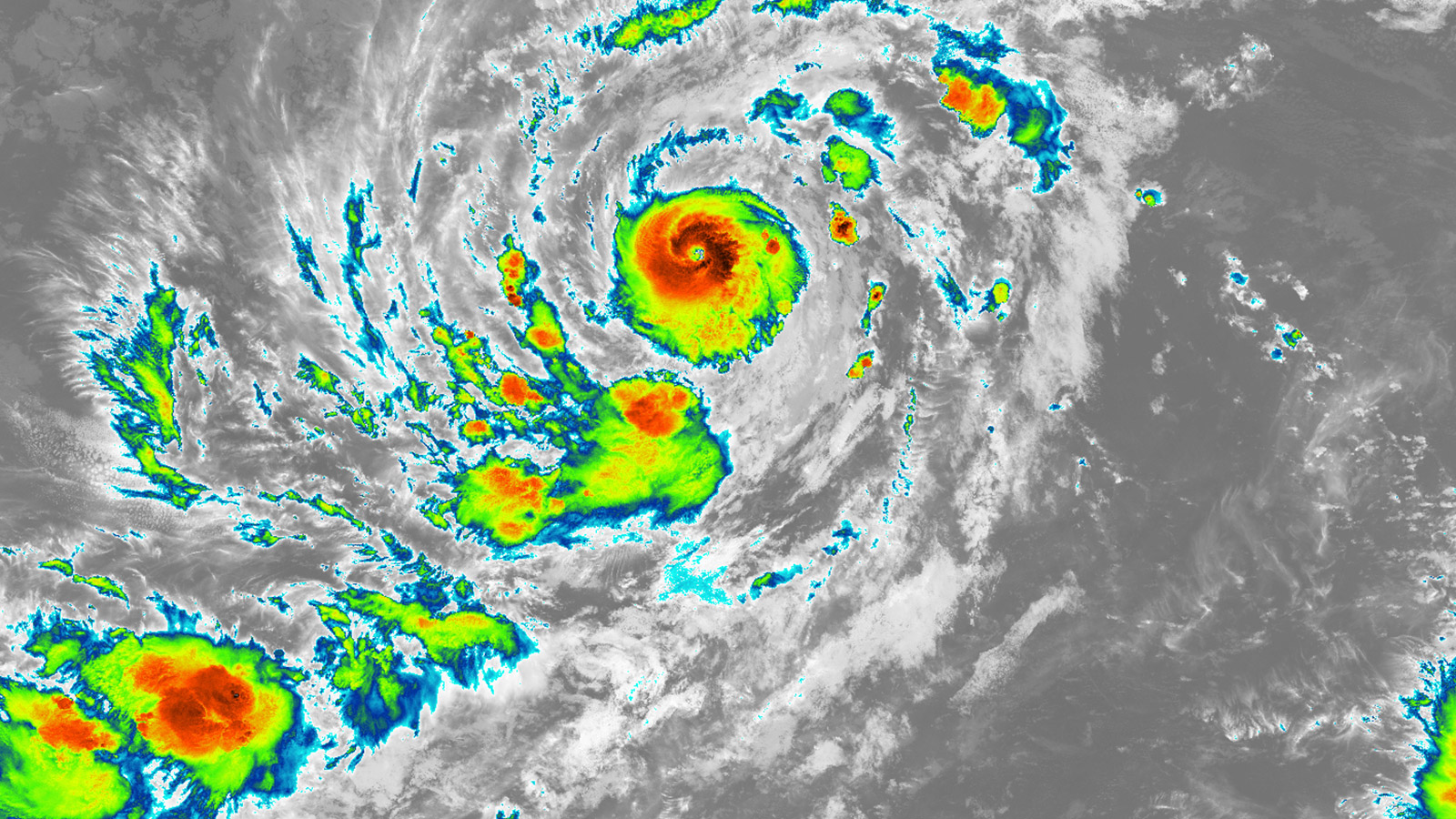

Hurricane Irma formed early Wednesday in the warm waters off the coast of West Africa — and took just 30 hours to strengthen to a Category 3. That’s the fastest intensification rate in almost two decades. By Friday afternoon, the storm had also grown noticeably larger in size with a well-defined eye, a classic sign of a strong hurricane.

Though Irma poses no immediate threat to land, the outlook is ominous: In the Atlantic, Irma is expected to pass through some abnormally warm waters — the primary fuel source for storm systems. The official National Hurricane Center forecast says it will remain at major hurricane status for at least the next five days, and, in a worst-case scenario, Irma could eventually grow into one of the strongest hurricanes ever seen in the Atlantic.

Possible tracks for Hurricane #Irma. All options are on the table, including the storm staying over water. Let’s not panic yet. pic.twitter.com/kppI6CrWR2

— Tim Heller⚡️ (@HellerWeather) September 1, 2017

That assessment is leaving forecasters and coastal residents understandably jittery. A hurricane this far out at sea normally wouldn’t draw this much attention, but Harvey’s floodwaters are still receding, leaving behind historic damage in Texas and Louisiana. This is not a normal situation.

Irma is “starting to give me that uncomfortable feeling in my gut,” wrote meteorologist Brendan Moses on Twitter. Another meteorologist, Michael Ventrice, said some of the initial modeling of Irma output “the highest windspeed forecasts I’ve ever seen in my 10 yrs of Atlantic hurricane forecasting.” Even the National Hurricane Center forecaster tasked with constructing the storm’s official forecast was surprised by how “uncommonly strong” Irma already is.

Hurricane Irma is what meteorologists call a “Cape Verde hurricane,” named after the African island nation just west of Senegal — an infamous late-summer breeding ground for powerful long-track storms. Some of the most notorious hurricanes ever to make U.S. landfall were born near where Irma generated.

Only about 15 percent of Cape Verde hurricanes directly strike the United States, so there’s no guarantee that Irma will. Since any potential landfall is still almost two weeks away and could take place anywhere from Texas to Maine, there’s not much for people to do right now except monitor the storm’s progress — and speculate.

On Friday, the National Weather Service warned of “fake forecasts” that are circulating widely on social media. But even established forecasting outlets have begun to share (rather cautiously) long-range graphics that show Irma threatening the U.S.

Meteorologists won’t have even a ballpark estimate of where Irma might make landfall or how strong it will be until early next week at the soonest. It will probably take a few more days to refine those forecasts enough to confidently call for preparedness actions.

But as of Friday, the most likely scenarios for Irma aren’t looking good.

- Florida and the Caribbean: Historically, Florida is the state most likely to be hit by a hurricane in September. Recent runs of the European model, the weather model with the greatest historical accuracy, showed a swath of the southeast coast from the Florida Keys to southern Virginia as the most likely area where Irma would make landfall. On the way, it could pass close to the islands of the northeast Caribbean.

- Northeast: A few recent model runs show Irma curving northward off the East Coast, potentially affecting the mid-Atlantic or New England. The large-scale North American weather pattern over the next 10 days may become especially chaotic due to a dwindling typhoon in the Pacific (the atmosphere is one giant connected system, after all), so it’s possible an unpredictable dip in the jet stream could steer Irma inland.

- Gulf of Mexico: Should a high-pressure area over the western Atlantic remain in place, Irma could scoot underneath it, passing through the northern edge of the Caribbean and into the Gulf of Mexico. With the Gulf coast already devastated by Harvey, it’s a potentially tragic scenario that can’t yet be ruled out.

- Out to sea: Most hurricanes that form where Irma did don’t make landfall in the United States at all. They safely curve out to sea. If we’re lucky, Irma might do the same.

It’s peak hurricane season, so it’s no surprise to see another strong storm spinning across the Atlantic. But with Irma’s path still to be determined, the best place to focus our attention now is on helping soothe the disaster that’s already happened in Texas and Louisiana.