Recent environmental victories, including President Obama’s rejection of the Keystone XL pipeline, owe a lot to the fracking boom. A recent glut of oil and gas in the United States opened a window of opportunity, making a number of key environmental policies more politically palatable.

But those who care about the climate should be asking a hard question: What will happen to such policies if the fracking boom fizzles?

The U.S. boom in fracking has tapped huge deposits of natural gas locked up in shale rock, pushing the nation’s natural gas production to an all-time high.

Production rose so fast it outstripped demand, creating a glut that has pushed prices down. Enjoying some of the lowest natural gas prices in the world, utilities have cut back on coal use and burned more natural gas for generating electricity. The shift has been remarkably fast, and today natural gas and coal have equal shares of the U.S. electricity market.

Meanwhile, as this fracking boom unfolded, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was crafting a series of rules limiting greenhouse gas emissions from coal-fired power plants. Rules proposed in 2013 and finalized this year practically bar the building of new coal plants for the time being, giving an advantage to natural gas.

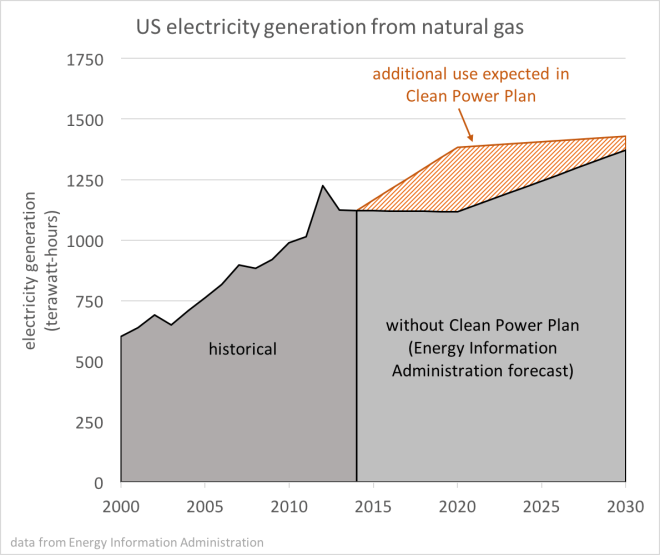

Further rules on existing power plants were recently finalized as the Clean Power Plan, which will give natural gas an additional boost over coal. Analyses by the EPA and the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) expect that utilities will continue switching from coal to natural gas, as a relatively cheap way of helping meet targets for cutting emissions.

(The EPA calculates that generating electricity with natural gas creates about half as much greenhouse gas emissions as using coal. However, natural gas can leak from pipelines and other infrastructure, releasing its main component, methane — a potent greenhouse gas — into the atmosphere. Some recent studies suggest the EPA may be underestimating such leakage, so that actual emissions from natural gas may be closer to those from coal.)

Such policy changes have been aided by the fracking boom, which made it much cheaper to shift from coal to natural gas. But whether the nation continues to move away from coal — and how quickly — could depend on how long the fracking boom lasts, and how long natural gas prices remain low.

The fracking boom has also pushed U.S. oil production up to near-record levels. That fast-rising production — along with economic weakness worldwide — led oil prices to plummet in late 2014, and to remain around $50 a barrel throughout this year.

The boom has helped to slash the nation’s dependence on foreign oil over the past five years, and tempered demand for oil from Canada’s tar sands. With the oil price drop of late, many new tar-sands projects look unprofitable, so they have been delayed or canceled.

As a result of these shifts, the push for the Keystone XL pipeline lost some steam — and then finally, earlier this month, President Obama rejected the pipeline.

Waning shale

In pointing out how the fracking boom has played a crucial role in enabling these policy shifts, I don’t want to detract from activists who protested against Keystone XL, or lawyers who fought in the Supreme Court to uphold the EPA’s jurisdiction to regulate greenhouse gases.

My reason for bringing up the role of fracking is to ask: What happens if the shale boom truly goes bust?

There are signs that this may be happening already. Companies fracking in the nation’s major shale oil zones, like North Dakota’s Bakken and Texas’ Eagle Ford, have cut back drastically on their spending. Yet today, most of these frackers are losing money. The current situation clearly can’t last. Either fracking needs to be cut back further, or oil prices need to rise substantially.

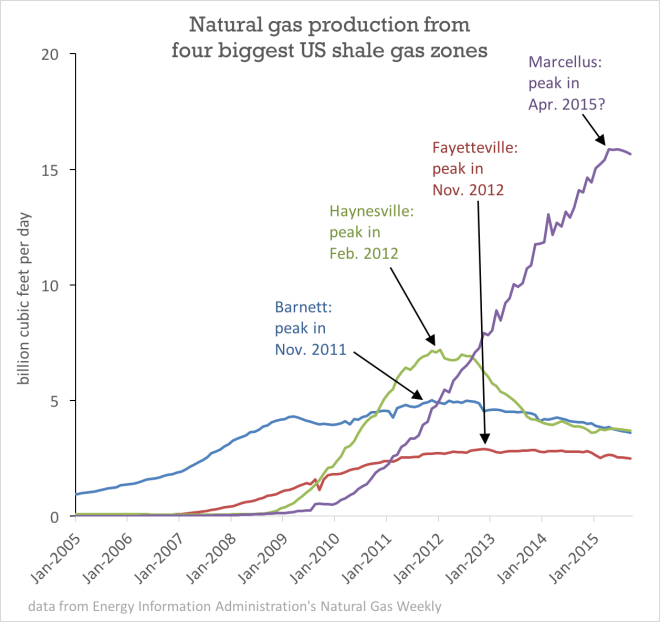

Similarly, America’s natural gas producers are struggling to maintain production at today’s low prices. According to EIA data, in nearly all the nation’s major shale gas zones — including the biggest of all, the Marcellus — production is now falling.

According to the most rigorous studies yet publicly released, by a team at the University of Texas in Austin, even if natural gas prices were to rise gradually over the coming decades, the nation’s major shale gas regions may have only another five years or so of growth left.

My worry is that natural gas and oil prices will shoot back up, driving a return to coal, an expansion of tar-sands extraction, and more generally a push to scrap limits on greenhouse gas emissions.

With higher natural gas and oil prices serving as a brake on the U.S. economy — and economic growth worldwide — I fear these short-term economic interests will trump the long-term effort required to tackle climate change.

Staying the course

To avoid this kind of reversal, the United States needs to continue and expand efforts that will accelerate cuts in greenhouse gas emissions.

Most proposals for drastically cutting greenhouse gas emissions involve a cap on overall emissions, and a significant price tag attached to those emissions that are allowed. Today, such policies are a non-starter in the U.S. Congress, given many members’ denial about climate change and their general opposition to regulations. But these policies can be implemented in individual states, as California has recently done.

To accelerate the rollout of renewable energy, the country can reinstate tax credits that aided wind, and extend tax credits for solar that are due to expire at the end of 2016.

Finally, the nation can greatly expand its spending on energy research and development, as Bill Gates has recently called for, laying the ground for the next generation of clean energy technologies.

My hope is that if oil and natural gas prices do shoot back up, alternative sources like solar, wind, and electric vehicles will have made enough progress to be able to better compete. But even so, the transition to clean energy will require the enactment of wise, increasingly strict policies — and keeping them in place— whether oil and gas prices are low or high.

——

Mason Inman is an award-winning journalist and author of the upcoming book The Oracle of Oil: A Maverick Geologist’s Quest for a Sustainable Future, now available for pre-order.