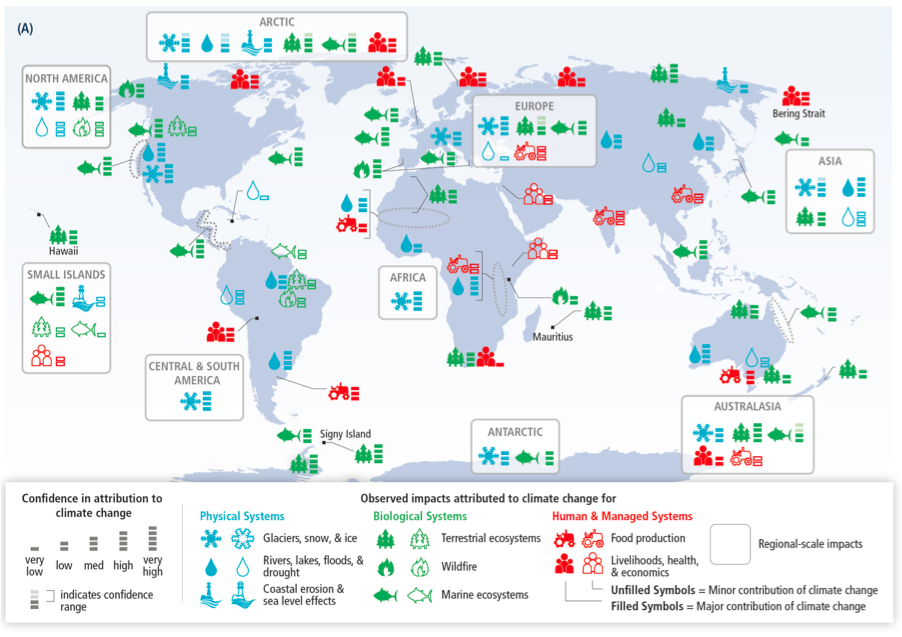

Climate change has broken down the floodgates, pervading every corner of the globe and affecting every inhabitant. That was perhaps the clearest message from the newest report of the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change — the latest in a conga line of warnings about the need to radically and immediately reduce our use of fossil fuels.

Published Sunday, it’s the second installment of the IPCC’s fifth climate report. The first installment was released last September; the third comes out next month. (If you’re wondering WTF the IPCC even is, here’s an explainer.) This latest installment catalogues climate impacts that are already being felt around the world, including floods, heat waves, rising seas, and a slowing in the growth of crop yields:

As we reported when a draft of key parts of the document was leaked in November, the IPCC says current risks will only worsen — risks such as food crises and starvation, extinctions, heat waves, floods, droughts, violent protests, and wars.

Natural Resources Defense Council President Frances Beinecke called the report an “S.O.S. to the world,” reminding us that failure to “sharply curb carbon pollution” will mean more “punishing rainfall, heat waves, scorching drought, and fierce storm surges,” and that the “toll on our health and economy will skyrocket.”

But the report doesn’t just focus on climate change’s risks and threats — it looks at ways in which national and local governments, communities, and the private sector can work to reduce those threats. And some of the news on climate adaptation is actually, gasp, slightly encouraging!

“Adaptation to climate change is transitioning from a phase of awareness to the construction of actual strategies and plans,” chapter 15 says. “The combined efforts of a broad range of international organizations, scientific reports, and media coverage have raised awareness of the importance of adaptation to climate change, fostering a growing number of adaptation responses in developed and developing countries.”

Farmers are adjusting their growing times as they adapt to changing local climates, for example. Wetlands and sand dunes are being restored to protect against storm surges and flooding, drought early-warning systems are being established, and governments are turning to the traditional knowledge held by their indigenous communities for clues on how best to cope with the increasingly hostile weather.

But the report highlights a depressingly unjust fissure between the world’s rich, who have caused most of the global warming but can afford to adapt to some of it, and the world’s poorest countries and communities, where countless lives can be ruined en masse by a single unseasonably powerful storm or drought.

“Climate change is expected to have a relatively greater impact on the poor as a consequence of their lack of financial resources, poor quality of shelter, reliance on local ecosystem services, exposure to the elements, and limited provision of basic services and their limited resources to recover from an increasing frequency of losses through climate events,” chapter 14 says.

And the report highlights the yawning gap between the amount of money that needs to be spent on climate adaptation and how much is actually being spent. Chapter 17 cites a World Bank estimate that it will cost the world $70 billion to $100 billion a year to adapt to the changing climate by 2050 (but notes that these figures are “highly preliminary”). Yet actual spending in 2012 was estimated to be around $400 million.

Those high adaptation costs will be out of reach for many of the world’s poorest countries — something that IPCC delegates from the U.S. and other Western countries don’t want you to think about. The New York Times reports that the World Bank’s $100 billion figure was scrubbed from the report’s 44-page summary at the last minute under pressure from rich countries, which have been spooked by poor countries’ calls during recent negotiations for climate compensation and far-reaching adaptation assistance.