Pete SouzaPresident Obama and Swedish Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt participate in a joint press conference.

During a press conference with Sweden’s Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt on Wednesday afternoon Stockholm time, President Obama was asked what the United States could learn from Sweden. His first thought was sustainable energy development:

What I know about Sweden, I think, offers us some good lessons. No. 1, the work you have done on energy I think is something the United States can and will learn from. Because every country in the world right now has to recognize if we are going to continue to grow and improve our standard of living while maintaining a sustainable planet, we are going to have to change our patterns of energy use. And Sweden I think is far ahead of many other countries.

So what can the U.S. learn from Sweden?

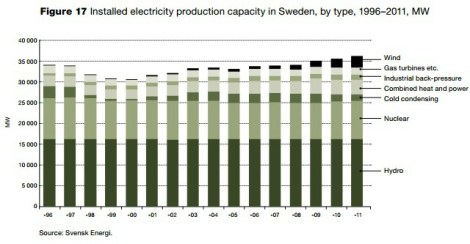

Sweden gets most of its electricity from hydroelectric and nuclear power, dating from investments in the ’50s and ’60s. Renewable energy — mainly wind — has also been on the rise, such that right now, over 47 percent of all energy consumed in Sweden comes from renewable sources. The vast majority of the electricity mix comes from renewables and nuclear:

But this hasn’t happened on its own. The switch is the result of a concerted effort to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, which in the mid-’70s had constituted around three-quarters of total energy supply. The main driver has been a long-standing and uncontroversial carbon tax.

Sweden began taxing carbon emissions back in 1991, at around $133 per ton. The system has changed a bit over the years, with industry paying less of the tax and consumers paying more, and the tax up to around $150 per ton. Daniel Engström, the director of climate at the Forum for Reforms, Entrepreneurship and Sustainability in Sweden, said that Sweden does not have as many climate deniers as the U.S. does (most Swedish energy critics are of onshore wind farms). There have been some concerns about higher fuel prices, but because oil is so expensive to import, and the carbon tax went into effect so long ago, and because biofuels are an increasingly feasible option, many people do not notice the carbon tax. Revenues have been high, the tax is efficient, and emissions have dropped more than expected.

According to the IEA [PDF], “Sweden has the lowest share of fossil fuels in the energy supply mix among IEA member countries.” Oil accounts for 27 percent of the total energy supply, and has been steadily losing ground to biofuels. The country imports all of its oil — and more than half of those imports come from Russia. Total domestic demand has actually dropped [PDF] since 1985.

Other fossil fuels are a similarly small share of the electricity mix. Only 3 percent of the country’s total energy production comes from gas. Most of the coal used in Sweden is used for industrial purposes — it barely registers as an electricity generator.

Even so, Sweden is committed to reducing carbon emissions by 40 percent by 2020. The country also invests in renewable energy through a market-based certificate system.

After the press conference with the prime minister, President Obama visited an energy expo at Stockholm’s Royal Institute of Technology. He spoke with people at Volvo who are aiming to have fully electric public transit buses up and running by 2015, which would pay for themselves within 10 years. Obama also looked at some fuel cell and electric personal vehicles, and posed the challenges of scaling up such a system as a “chicken and egg” question: “In the United States, one of the challenges has to do with distribution … if I was going shopping, where am I gonna refuel, right?”

Sweden’s longstanding carbon tax and emissions and renewable targets have been in operation while the nation thrived economically as much of the rest of Europe fell to pieces. C. Fred Bergsten, director emeritus at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, said that “Sweden has one of the lowest inflation rates in Europe; it runs a budget surplus every year; its corporate tax rates are considerably lower than U.S. rates; and it spends more on research and development, as a share of its economy, than we do.”

So it seems that the main thing the U.S. can learn from Sweden on energy policy is that carbon pollution is not essential to economic success.