Opponents of the coal-export terminal, clad in red, raise their hands in support of a speaker at the Seattle hearing.

Last Thursday, I braved the hordes crowding Seattle’s convention center to offer their opinions on a proposed coal-export terminal, proposed for construction just north of Bellingham, Wash., that would ship coal arriving on trains from the Powder River Basin overseas to Asia. Buzz about this event — a public hearing intended to gather input on what should be studied for the project’s environmental impact statement — had been building for weeks. Turnout at previous hearings in other towns exceeded expectations (over 450 people showed up in Friday Harbor, the seat of a rural island county with a population of less than 16,000), prompting organizers to reschedule the Seattle hearing so it could be held at a convention center ballroom with a 2,000-person capacity, instead of a community college.

At a rally and news conference before the official hearing, I saw all the old environmental-protest standbys: a giant fish, a giant inflatable inhaler, an inflatable Earth, a hand-lettered sign reading “No coal train, yes Coltrane,” and last but not least, a lady dressed as Santa Claus comforting someone dressed as a polar bear. And much of the following testimony came straight from Bleeding-Heart Environmentalism 101: appeals from white people to think seven generations into the future, anti-coal slogans sung painfully to the tune of Christmas carols, etc. (When a group called the “Raging Grannies” took to the mike to offer such a performance, I heard one of the few terminal supporters in attendance groan “oh, God …” as her stereotype of crazy treehuggers was confirmed with frightening accuracy.)

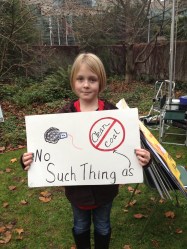

Opposition to the coal-export terminal spanned generations.

But to me, those clichés were really more of a distraction from the impressively diverse range of interests opposed to the terminal. A pastor, a Muslim woman, and a Jewish man each spoke of the obligation to protect and care for God’s creation. A young mother-to-be who shared fears for her unborn son. Pete Knutson, a commercial fisherman for 40 years who runs Loki Fish Company in Seattle, spoke on behalf of “all those marine livelihoods” that would be affected not only by the huge increase in barge traffic carrying coal from the terminal out to sea, but also by the “deadliest catch of all” — the ocean acidification caused by increased carbon emissions.

Nurses and doctors voiced concern about the health impacts of coal dust and diesel fumes from trains, as well as the delays to emergency vehicles that increased rail traffic could cause. Small business owners worried about the economic harm of increased congestion. Native leaders protested the assault on their treaty fishing rights and sacred cultural grounds (Cherry Point, site of the proposed terminal, is home to a Lummi Nation burial site).

Ranchers came all the way from Montana to make themselves heard — because although the coal in question would originate in Montana and Wyoming before traveling by train to the Pacific, residents in those states haven’t even had a chance to comment on the environmental review.

“The Corps of Engineers isn’t having any hearings in Montana,” said Brad Sauer, who runs Golder Ranch near Colstrip in the southeastern part of the state. “This proposed action isn’t just about Cherry Point, but the coal mining 1,000-plus miles away.”

That’s the technicality on which pro-terminal constituencies disagree. The cumulative impacts of these coal trains (up to 18 a day, each a mile and a half long, on Burlington Northern Santa Fe’s already overcrowded rail system), as well as the impacts of their dirty cargo, have opponents calling vehemently for the environmental review to look beyond the terminal itself. But supporters want it to consider only the impacts of the terminal on its immediate surroundings.

Terminal supporters spoke of the desperate need for jobs.

“I think [the terminal] should be judged on its own merit,” said Chris Johnson, a member of the Laborers’ Union who came down from Bellingham for the Seattle hearing. “If the project is feasible, build it,” he said. “If it isn’t, don’t build it.”

A common pro-terminal argument maintains that China’s demand for coal means the stuff will end up being exported and burned anyway, if not from Cherry Point, then from British Columbia or elsewhere. With coal profits declining steadily, the industry now pins its hopes for survival on Asian demand for cheap energy.

“Trust me, that coal’s going to China,” Johnson said. “Why not build [the terminal] and get the tax revenue and jobs in this country?”

To the anti-coal contingent, that’s like saying that heroin addicts are going to shoot up anyway — why let the drug kingpin on the other side of town reap all the benefits of their self-destruction? Because coal is the heroin of fossil fuels; climate hawks will tell you that any hope for curbing runaway climate change — a hope fast slipping out of our grasp — requires an immediate end to mining and burning coal, the dirtiest energy source out there. To the extent that we facilitate the continued production of coal, we are complicit in the devastation of the climate, just as a drug dealer is complicit to some extent in a customer’s death.

Besides, China is already investing in renewable energy. Limiting access to cheap coal — by, say, refusing to build export terminals in the Northwest (even if more ultimately end up being built in Canada) — only encourages further clean-energy progress in Asia.

“If you are worried about climate or air quality, it’s really hard to imagine how you could live with the environmental impact of 150 million tons of coal,” said Dan Jaffe, an atmospheric and environmental professor at the University of Washington-Bothell, in reference to the total amount of coal that would be shipped from all five terminals currently under consideration. (Deals are also in the works for coal-export facilities in Longview, Wash., and Boardman, Coos Bay, and Port of St. Helens, Ore. Plans for a sixth proposed terminal in Hoquiam, Wash., were scrapped in August.)

Public opinion at every hearing has been overwhelmingly anti-coal, and after it was revealed that pro-coal interests had paid people to hold spots in line before a hearing in Spokane to guarantee their testimony, organizers switched to a lottery system to determine who could testify. King County Executive Dow Constantine, Seattle Mayor Mike McGinn, and the Seattle City Council have come out strongly against the terminal, and close to 40 other cities, counties, and ports; 600 health professionals; over 200 faith leaders; and more than 400 local businesses have voiced concern or opposition — in addition to the usual environmental and community groups.

For those supporting the terminal — several of whom claimed, in their testimony, to be lifelong environmentalists — the issue comes down to the magic word: jobs. “Our members need jobs so desperately,” Johnson said. “[Terminal operator] SSA Marine made a commitment to build 100 percent union — construction and operation. Seven hundred and fifty construction jobs for two years.”

The debate here over coal-export terminal jobs sounds a lot like the one over Keystone XL Pipeline jobs: Many opponents made clear that they support unions, and a few mentioned that they, too, had been out of work for a long time, but still didn’t think the terminal jobs, many of them temporary, were worth it. But anyone who’s been broke before knows that two years doesn’t sound temporary; two years of a good union job could be enough to settle some of your debts, to move to a better place, to maybe even start saving.

Coal shouldn’t mean jobs. Solar and wind should mean jobs. But when lawmakers consider those industries worthy of barely a scrap of the subsidies allotted to fossil fuels, this is what it comes down to: people who need jobs “desperately” having to plead their case in front of hundreds of others booing and giving them thumbs down.

I’ve experienced plenty of skepticism (at best) and scorn (at worst) from people who think I’m stupid to go into journalism because it’s a dying industry. Why is that such a widely held opinion, while coal — a truly dying industry — is kept on life support by government subsidies, propped up as the savior for struggling communities?

We should not, under any circumstances, build the Gateway Pacific Terminal at Cherry Point. We should pull the plug on coal — and pour those long-wasted resources into industries that promise jobs, permanent jobs, at no cost to human health or the climate.