Ryan Rodrick Beiler / ShutterstockVan Jones.

The traditional environmental movement has a diversity problem.

That’s according to Van Jones, founder of Green for All and environmental and civil rights advocate. But Jones says it’s not just that the staffs of many large, mainstream environmental organizations have been historically mostly white — it’s that most of the smaller environmental justice groups are getting a fraction of the funding that the big groups receive.

Jones says for the environmental movement as a whole to succeed, that needs to change. Environmental justice groups are the ones serving populations that are often most vulnerable to climate change and affected most by pollution — Americans who are low-income, live in cities, and are often people of color.

“The mainstream donors and environmental organizations could be strengthened just by recognizing the other ‘environmentalisms’ that are already existing and flourishing outside their purview,” Jones said.

These environmental justice groups work on a smaller scale than the major mainstream groups like the Sierra Club and Environmental Defense Fund — they’re groups like the Bus Riders Union in Los Angeles and West Harlem Environmental Action (WE ACT) in New York City, groups that are working towards improving the environmental health of their communities. Danielle Deane, Energy and Environment Program Director at the Joint Center, said the groups don’t always get the credit they deserve for their support of environmental issues.

“For whatever reason, often the innovation, the hard work by community leaders that’s happening to help prepare their cities as they expect extreme weather events like Sandy, often those leaders don’t get the level of attention they deserve even though they’ve been working on some of these issues for decades,” she explained. “I think that’s slowly changing, but I think there’s a lot more activity by a wide range of folks that isn’t yet getting its due.”

One of the biggest reasons for that, as Jones said, is the funding gap that exists between the small-scale environmental justice groups and the large, mainstream environmental organizations. A recent report [PDF] from the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy found from 2007 to 2009, just 15 percent of environmental grants went towards benefiting marginalized communities, and only 11 percent went towards advancing “social justice” strategies.

One of the biggest reasons for that, as Jones said, is the funding gap that exists between the small-scale environmental justice groups and the large, mainstream environmental organizations. A recent report [PDF] from the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy found from 2007 to 2009, just 15 percent of environmental grants went towards benefiting marginalized communities, and only 11 percent went towards advancing “social justice” strategies.

The Washington Post investigated the issue in March and found that environmental justice-focused organizations operate “on shoestring budgets.” In fact, according to the Post, a 2001 report found the environmental justice movement gets just 5 percent of the conservation funding from foundations, with mainstream environmental groups getting the rest.

Jones said diversifying the donor lists of foundations that usually give to environmental groups would help black Americans in particular make their voices heard in the environmental movement. Polls show that, as a group, black Americans support environmental and climate change specific regulations as much or more than white Americans do. A 2010 poll [PDF] from the Joint Center found black Americans in four swing states supported action on climate change and a solid majority of respondents said they wanted the U.S. Senate to pass legislation that would reduce greenhouse gas emissions before the 2012 election. The poll also found a majority of respondents said they would be willing to pay up to $10 per month more in electric rates if the extra charge if it meant climate change was being addressed, and more than 25 percent said they would pay an additional $25 per month.

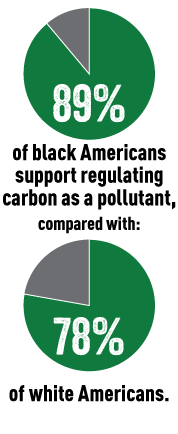

A Yale poll [PDF] from 2010 yielded similar results: it found Hispanics, African Americans, and people of other races and ethnicities were “often the strongest supporters of climate and energy policies and were also more likely to support these policies even if they incurred greater cost.” It also found 89 percent of black respondents said they would strongly or somewhat support regulating carbon as a pollutant, compared to 78 percent of white Americans.

“I think there’s always been way more support in the black community for climate solutions and environmental solutions than we have credit for,” Jones said. “Some affluent white communities are more vocal and maybe have more intensity, and also more resources to single this one issue out, but the polling data’s pretty clear that African Americans are among the most supportive of environmental regulation and climate solutions.”

Deane agrees. She said black Americans have reason to care about the environment, because they’re one of the groups most affected by its health. A 2008 study found 71 percent [PDF] of black Americans live in counties in violation of federal air pollution standards, compared to 58 percent of white Americans. That increased exposure to pollution contributes significantly to the high rate of asthma in the community — black children are twice as likely [PDF] to have asthma as white children, and overall, black Americans have a 36 percent higher rate of asthma than whites. In addition, according to the 2008 report, 78 percent of black Americans live within 30 miles of a coal-fired power plant, compared to 56 percent of non-Hispanic whites. Blacks are also 52 percent more likely to live in urban heat islands than whites, which makes them more vulnerable to heat waves.

Deane agrees. She said black Americans have reason to care about the environment, because they’re one of the groups most affected by its health. A 2008 study found 71 percent [PDF] of black Americans live in counties in violation of federal air pollution standards, compared to 58 percent of white Americans. That increased exposure to pollution contributes significantly to the high rate of asthma in the community — black children are twice as likely [PDF] to have asthma as white children, and overall, black Americans have a 36 percent higher rate of asthma than whites. In addition, according to the 2008 report, 78 percent of black Americans live within 30 miles of a coal-fired power plant, compared to 56 percent of non-Hispanic whites. Blacks are also 52 percent more likely to live in urban heat islands than whites, which makes them more vulnerable to heat waves.

“I think there’s still a disconnect where the public perception of who really cares about environmental issues and who wants action on climate — a disconnect between what’s happening on the ground and public perception, ” Deane said. “Because African Americans know they tend to suffer disproportionately from pollution, you tend to see high levels of support for action to make sure companies all have to meet higher standards, but often when you see environmentalists you tend to see folks that are not necessarily as diverse as what we know and what we see on the ground.”

Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee (D-Texas), co-chair of the Congressional Black Caucus’ Energy, Environment and Agriculture Task Force, says fighting for environmental causes is about much more than protecting natural resources — to her, environmental issues are civil rights issues. Just recently in her own district of Houston, she helped fight against a grease recycling plant that was proposed for a residential neighborhood.

“I’ve found the black community to be very well informed about environmental issues, and that’s because they live them every day,” she said. “One of my minority neighborhoods had to fight against a cement factory. Another had to fight against a waste facility in their community. So most African Americans know what it is to try to keep their neighborhood well. That makes them more sensitive, it makes their members more in tune.”

Jackson Lee says environmental justice weaves into all the decisions the CBC makes. According the League of Conservation Voter’s annual environmental scorecard, the lifetime environmental voting record of the current members of the CBC is 86 percent — meaning they voted in favor of environmental issues 86 percent of the time. And in 2009, Jones said, every member of the CBC except one — Rep. Artur Davis (R-Ala.) — voted in favor of the Waxman-Markey cap-and-trade bill, making the CBC one of the “greenest” caucuses of the last Congress.

Jones said there’s long been tension between mainstream environmental groups and environmental justice organizations. Mainstream groups can feel like they’re unfairly being called racist and that claims of lack of support for environmental justice groups can be unfounded, and environmental justice groups often are jealous of the publicity and funding the mainstream groups get and wary to reach out to them for fear of being rejected. But the onus to make the change, he said, isn’t on the environmental justice groups — it’s the donors and foundations who need to expand who they send their money to, and mainstream environmental groups have the power to help them do that.

Jones said there’s long been tension between mainstream environmental groups and environmental justice organizations. Mainstream groups can feel like they’re unfairly being called racist and that claims of lack of support for environmental justice groups can be unfounded, and environmental justice groups often are jealous of the publicity and funding the mainstream groups get and wary to reach out to them for fear of being rejected. But the onus to make the change, he said, isn’t on the environmental justice groups — it’s the donors and foundations who need to expand who they send their money to, and mainstream environmental groups have the power to help them do that.

“If you go to Detroit, you will find lots of community gardening going on, lots of community cleanup going on, lots of small-scale manufacturing going on. None of this is being directed by any mainstream environmental group — these are organic, well-considered responses from people who are trying to make their lives better,” Jones said. “Those people should be called environmentalists as much as anybody who is standing up for endangered species.”

Andrew Breiner contributed the graphics to this piece.