This story is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Here’s something rare in climate reporting: a bit of good news. Or, more accurately, not disastrous news.

As we explained last week, China has long exerted an outsize role in global climate change, not simply because it’s by far the world’s leading emitter of greenhouse gas, due largely to its enormous population, its rapid growth, and its reliance on dirty coal — but also because of China’s influence over global politics as a hold-out in international climate deals.

Now the reigning heavyweight contributor to global warming might be slimming down a bit.

China’s greenhouse gas emissions are likely to peak, and then begin to taper, around 2025, according to a new report. That’s five years ahead of a promise made by China’s leader, Xi Jinping, in November 2014, as part of China’s historic climate accord with the United States.

The new analysis, released Monday by the London School of Economics, says China’s emissions “could peak even earlier than that” and begin to fall rapidly thereafter, holding out a tantalizing possibility: The world could stay within the internationally agreed-upon limit of 2 degrees C (3.6 degrees F) of warming above pre-industrial levels, according to the authors. That limit is seen by scientists as a crucial threshold to stay within to prevent some of the most dangerous impacts of climate change. It’s also a limit world leaders hope to enshrine in an international agreement in Paris later this year.

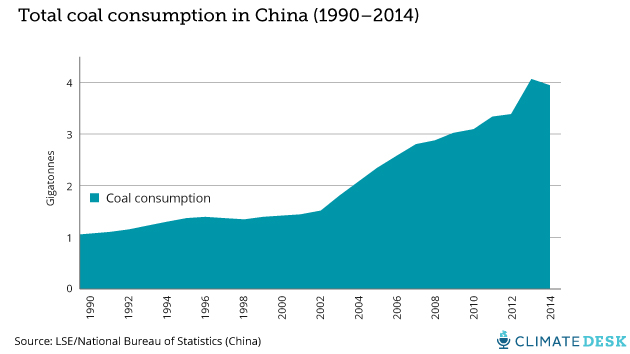

The findings are all the more startling when you consider that the growth in China’s coal consumption has been responsible for more than half of global CO2 emissions growth in the last decade, according to a separate Greenpeace analysis.

“Whether the world can get onto that pathway in the decade or more after 2020 depends in significant part on China’s ability to reduce its emissions at a rapid rate, post-peak,” write Nicholas Stern and Fergus Green, the authors of the new LES report. Stern was also the author of the U.K.’s landmark “Stern Review” on climate economics.

Driving the shift in China is a decline in the importance of coal. “It is now possible to say with confidence that coal use in China has likely reached a structural maximum and begun to plateau,” the authors write, pointing to a recent dip in coal consumption in 2014 and in the first quarter of 2015. Natural gas use will increase rapidly over the next five to 10 years, the authors say. Combined with aggressive investment in alternative energy and new restrictions on coal consumption in response to China’s air pollution crisis, the gas boom will help tamp down greenhouse gas emissions.

The report’s authors cast a surprisingly upbeat tone when describing the structural changes in China’s energy sector, including its investment in cleaner technologies such as solar and wind and its pilot carbon pricing programs. “Eventually, this increasing momentum could unleash a large wave of clean energy investment, innovation and growth — a new energy-industrial revolution,” they write.

Bringing China’s emissions under control will also inspire political change, the authors argue: Continued strong action by China could silence critics in the West who justify their own inaction by using China as a climate bogeyman — a very common argument in the U.S. — and thereby “lower the political barriers in rich countries to stronger climate action.”

“China holds the keys,” Stern and French conclude.