Jay Gulledge was an academic ecologist for 16 years before he moved into his current role as an educator, researcher, and consultant on climate issues. He’s now the [deep breath] “Senior Scientist and Director for Science and Impacts at the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, a non-resident Senior Fellow at the Center for a New American Security, and a Next Generation Fellow of the American Assembly at Columbia University.”

Last year, Gulledge, acting under the aegis of climate nonprofit E3G along with co-authors Nick Mabey, Bernard Finel, and Katharine Silverthorne, produced a report called “Degrees of Risk: Defining a Risk Management Framework for Climate Security.” It’s about approaching climate change the way the national security community addresses its challenges, through the lens of risk management. I was late getting to it, but I wrote a post about the report last week. I also called Gulledge to chat about how the risk management approach can help clarify the climate conundrum.

Q. Why talk to national security people about climate?

A. National security questions, the important ones, are highly uncertain, but have high-impact outcomes if things go wrong. Iran’s trying to develop fissile material that could go into a bomb. When they might have a bomb, and what they might do with it, are highly uncertain questions with potentially really bad outcomes. That’s the kind of thing we’re dealing with on climate change. Because that’s the kind of question the national security community typically grapples with, they have a long history of developing risk management strategies and techniques that address various types of uncertainty.

Q. In what way has the typical approach to climate change differed from a security approach?

A. The climate problem has been approached from a traditional environmental policy framework — a tradition of point-source pollution, toxicity, criteria air pollutants — where it’s here and now, not an uncertainty about the future. Kids already have asthma. People are already contracting cancer at an elevated rate. And solutions are relatively clear: Put a scrubber on that stack.

Well, climate change doesn’t work that way. Climate change is a collective problem that’s based on a massive market failure. It hinges on how our entire economy runs, globally as well as nationally, which is energy sources that emit carbon. The primary consequences are intergenerational — they’re in the future — and are more widespread and more complex. It’s more of a syndrome than a disease, so to speak.

So it’s more akin to the threat of nuclear war. We don’t know if there will be one, who will start it, where the bomb will drop … but we can be pretty well assured the consequences are not something that we want to deal with. The security community has dealt with different types of problems than the environmental community has dealt with.

Q. Is the risk-management frame catching on?

A. The 2007 IPCC synthesis report says, for the first time, “climate change is an iterative risk management problem.” The scientific community as a whole hasn’t wrapped their heads around that statement, but it represents a paradigm shift. It took them 20 years and four reports to realize the way you grapple with this problem is not by predicting the outcome. It’s by taking the information you have, considering the uncertainties and their implications, and making some initial decisions on how to deal with it. Then, as you learn more over time, you go back and revisit those decisions and see whether or not they’re working for you, whether they make sense, and you make adjustments or throw them out and do something different.

Q. Our current political systems seem inadequate to the task.

A. They do, but the security community does it all the time. And they do it the midst of incredible animosity and strife. There are differences between the security policy community and the environmental policy community, but they’re not fundamental differences. They’re mostly cultural. Both poll really high among the public. The difference is the level of priority. The public will always put national security concerns above environmental concerns.

Q. One side of the uncertainty coin is in the climate science. The other side is policy uncertainty — whether your techniques and instruments will reach your carbon goals.

A. Once everyone agrees that the details and consequences are uncertain, but the cause isn’t, then pure economics tells you that your only choice is to start immediately reducing emissions. If you start late and it turns out that things are worse than you thought, you are screwed. But if you start early and it turns out that things aren’t as bad as you thought, you can take your foot off the accelerator. You don’t have that option if you haven’t gotten started.

Q. Can this framework help us get beyond the partisan clash of believers vs. deniers?

A. Look, there are ideological clashes in national security as well. Very much so! Whether or not to build a new weapon. Whether or not to sign a treaty with Russia to reduce nuclear arms. What [the risk-management framework] does is change the questions that you’re arguing over.

We should be arguing over the value of avoided risk. There can be partisan divides over that — you’re still going to have folks who ideologically don’t like regulation, you’re still going to have folks who don’t want to pay the price of regulations; that doesn’t go away — but it makes the debate more real and meaningful.

That’s what they do in the national security arena. They’re comfortable with uncertainty. They don’t like it. But they know it’s there and they’re going to grapple with it.

[What follows is some fairly nerdy discussion of cost-benefit analysis. You’ve been warned.]

Q. What do you think cost-benefit analysis misses? Why do you think it’s ill-suited to the climate problem?

A. It has a lot of problems. One is that there are a lot of non-market impacts involved with climate change, and cost-benefit is not designed to deal with non-market impacts — for example, the existence value of a forest or a species, the ability to engage in recreation of a certain kind.

Q. You’re perpetually seeing efforts to try to quantify those things …

A. Yeah, and they fail. In any way that satisfies the policy community, they fail. So far, anyway — I don’t want to demean the effort. So that’s one of the problems.

Another problem is that, because the impacts are intergenerational, economists are very strongly driven to apply discount rates that mean that within 30 years there is no value of action today.

A third problem is that the impacts are highly uncertain, and that’s not a strong suit of cost-benefit analysis. It’s very weak on accounting for uncertain impacts.

It is also designed to deal with reversible effects. Most of what climate change is going to bring will be irreversible — a new climate state.

Also, current [Office of Management and Budget] guidelines do not allow assumptions about risk aversion …

Q. That’s supposed to be baked into the discount rate, right?

A. The discount rate can have a risk-aversion factor built into it, but the OMB guidance disallows that. So the discount rate is time-preference only.

Q. What is the policy rationale for that?

A. In our system of governance, policymakers [not economists] are supposed to make the value-laden decisions. The problem is that once you give them the [discount rate], they accept it. If you give them a number that was calculated without a risk-aversion factor, they don’t know that.

You could say, “here’s a number if you’re not averse to risk, here’s another one if you are.” But OMB does not permit that. So OMB is a policymaker. Congress and the president are supposed to apply their values, but OMB advises both of them. The system doesn’t work.

Q. Do you think it’s fair to say that cost-benefit analysis has typically underestimated the climate problem, or recommended insufficient action?

A. In terms of policy, it comes into cost-benefit analysis as the “social cost of carbon.” So, for example, CAFE standards had a cost-benefit analysis and one of the considerations in that analysis was the social cost of carbon.

In my estimation, the social cost of carbon [that the U.S. government uses] is very low. It doesn’t account for non-market impacts, risk aversion, or uncertain outcomes. It says, “we run a model, the model says it’s going to warm by this much, we fit a damage curve to that level of warmth, we assume everything’s correct, and we get this number.”

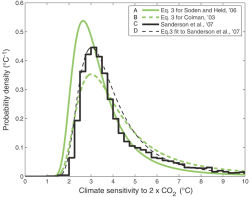

There are a lot of problems with that. It’s models on top of models. There’s an economic model on top of a climate model, etc. The problem is that you get your “best estimate” out of a climate model and you do not consider that long-tail risks on the end of the curve.

Risk is the probability of an outcome times its level of severity. So with this long tail on the right, there’s more chance that we would underestimate warming than there is we would overestimate it. There’s more probability space on the right than there is on the left.

If you just take the best estimate, you split the difference and say, “There’s just as much chance that we could be better off than we think as there is that we’ll be worse off.” But that’s not the case with climate change. That’s perhaps the most important thing that cost-benefit analysis is missing.

And if we can’t decide where that risk tail cuts off and probability drops to zero, then cost-benefit analysis literally can’t solve its equations. In the parlance, we say it “blows up.”

So they just choose a cutoff. And that’s not a bad choice if you’ve got something that approximates a bell curve, something that doesn’t have a really long tail on it. The consequences of cutting it off too short are pretty small — it’s already really close to zero. That’s just not the case for climate change. This is what Martin Weitzman at Harvard has been concerned about for years. Calls it the “Dismal Theorem.”

Q. In what way are economists getting risk aversion wrong?

A. They are using financial markets to determine what risk to apply to climate change. If you’re going to do that you have to accept what the markets really tell us, which is that people are averse to risk in their financial investments. We have different discount rates for high-risk investments versus low-risk investments.

Q. And isn’t there a difference between risk aversion for your own investments and risk aversion for the welfare of future generations?

A. There’s both a philosophical and ethical basis for that, as well as an observed practice. What is the traditional use for treasury bonds? You give it to your kids as a college fund. It’s for their future, or for your grandkids. You could give them more if you were willing to take a higher risk, but you also know that they could lose it and have nothing. So people behave differently depending on whether it’s their own risk versus something for their children.