This story was originally published by WIRED and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Last week, JetBlue announced it will offset its 15 billion to 17 billion pounds of greenhouse gas emissions by purchasing carbon credits and pumping cleaner-burning aviation fuel into planes landing at San Francisco International Airport. Great! Or is it? American corporations across the economy are trying to build up their green credentials, and carbon offsets seem to be the hammer of choice.

Investment and university pension funds, cement manufacturers, home heating distributors, tech giants like Google and Amazon, and the ride-hailing firm Lyft all say they are reducing their carbon footprint through similar offsets. Yet some critics worry the programs are an excuse to not take tougher measures to curb climate change. If not done right, the purchase of offsets can act as a marketing campaign that ends up providing cover for companies’ climate-harming practices.

When a company buys offsets, it helps fund projects elsewhere to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions, such as planting trees in Indonesia or installing giant machines inside California dairies that suck up the methane produced by burping and farting cows and turn it into a usable biofuel. What offsets don’t do is force their buyer to change any of its operations.

Supporters of offsets say they are only an acceptable tool once companies have done everything they can to pollute less, such as tightening up manufacturing processes, cutting down on office heating, or making delivery trucks run on cleaner fuels. Purchasing carbon offsets “is clearly better than doing nothing,” says Cameron Hepburn, who directs Oxford University’s economics of sustainability program. They can also help finance emerging green practices, technologies, and services that otherwise might struggle to find customers. “We know we will have to remove a lot of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, and offsets are helpful in priming that market,” Hepburn says. But he and others caution that carbon offsets still need third-party verification to make sure they do what they are supposed to do, and that the specific carbon-reducing action wouldn’t have been taken otherwise.

That’s where it gets messy, says Barbara Haya, a research fellow at U.C. Berkeley, where she studies the effectiveness of carbon offset programs. “What would JetBlue have done if they couldn’t buy offsets?” Haya says. “Would they have put money into efficiency of the planes, or invested in future biofuels to create a long-term alternative to fossil fuels? That’s the fundamental question we have to ask for voluntary offsets: How much is it taking the place of real long-term solutions?”

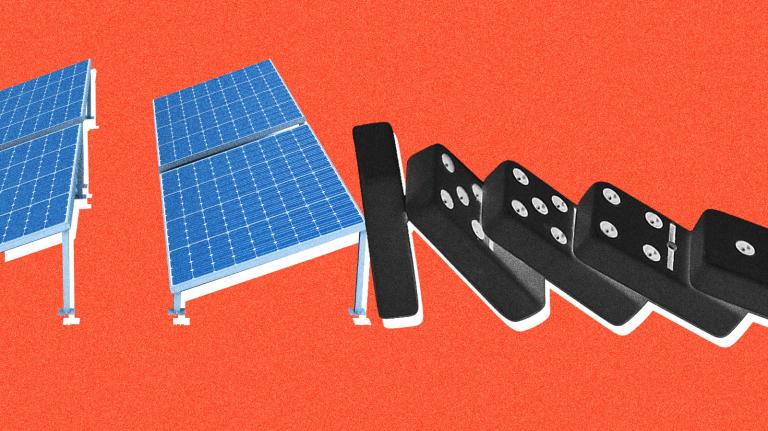

Haya points to JetBlue’s investment in sustainable aviation fuel as a big plus, unlike some airlines that only buy the offset and continue with business as usual. Haya is helping the University of California’s 10 campuses become carbon neutral by 2025. To reach that goal, the university system will have to both cut back on energy use and purchase offsets. Because solar and wind power are now price-competitive with fossil fuel-generated electricity in California, using those renewable sources of energy is good for the planet and helps the university reduce its emissions, but it won’t qualify as a carbon offset, Haya says.

Instead, the big push in California now is for forest regeneration (namely, planting more trees) and changing farming practices. Disney, ConocoPhillips, and Poseidon Resources bought $6.7 million worth of offsets to restore and replant a 100-acre parcel of a state park in the mountains west of San Diego. In 2018, the latest year for which data is available, such nature-based solutions accounted for a reduction of 100 million metric tons of CO2 globally, according to a recent report by the nonprofit group Forest Trends. That reflects about $300 million in purchased offsets.

Although 2018 was a record high for carbon offsets and 2019 looks to have been similarly strong, those 100 million metric tons are still just a tiny drop in the greenhouse gas bucket. Last year, industrial CO2 emissions reached nearly 37 billion metric tons, according to a report by the Global Carbon Project.

Still, there are signs that offsets might help in the long term by forcing carbon-polluting industries to become a bit more creative. A Swiss livestock company, for example, sells a special garlic-and-citrus cattle feed supplement to help cows produce less methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. It just gained approval from Verra, a nonprofit that develops standards for carbon offset projects. Farmers who use the feed and lower their methane emissions can then, after an audit, sell the carbon credits as an additional source of income.

Projects aren’t working everywhere, however. A 2019 investigation by ProPublica found Brazilian forest-based carbon offset projects failed because loggers cut down trees after the offsets were sold to U.S. and European corporations. “You have to have an approved methodology and make sure the science is sound,” says Naomi Swickard, Verra’s chief market development officer.

Swickard acknowledges that carbon offset projects aren’t all created equal, and says the concept isn’t a solution to the climate crisis. But it may buy us a bit of time, time that is fast running out.