This story was originally published by High Country News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In September, President Donald Trump visited fire-ravaged California and declared that the wildfires that had already burned across millions of acres were the result of forest mismanagement, not a warming climate. “When trees fall down after a short period of time, they become very dry — really like a matchstick. No more water pouring through, and they can explode,” he said. “Also leaves. When you have dried leaves on the ground, it’s just fuel for the fires.”

Trump is right about one thing: Global warming isn’t the only reason the West is burning. The growing number of people in the woods has increased the likelihood of human-caused ignitions, while more than a century of aggressive fire suppression has contributed to the fires’ severity. In addition, unchecked development in fire-prone areas has resulted in greater loss of life and property.

Yet, much as California Governor Gavin Newsom told Trump, it’s impossible to deny the role a warming planet plays in today’s blazes. “Something’s happening to the plumbing of the world,” Newsom said.“And we come from a perspective, humbly, where we submit the science is in and observed evidence is self-evident that climate change is real, and that is exacerbating this.”

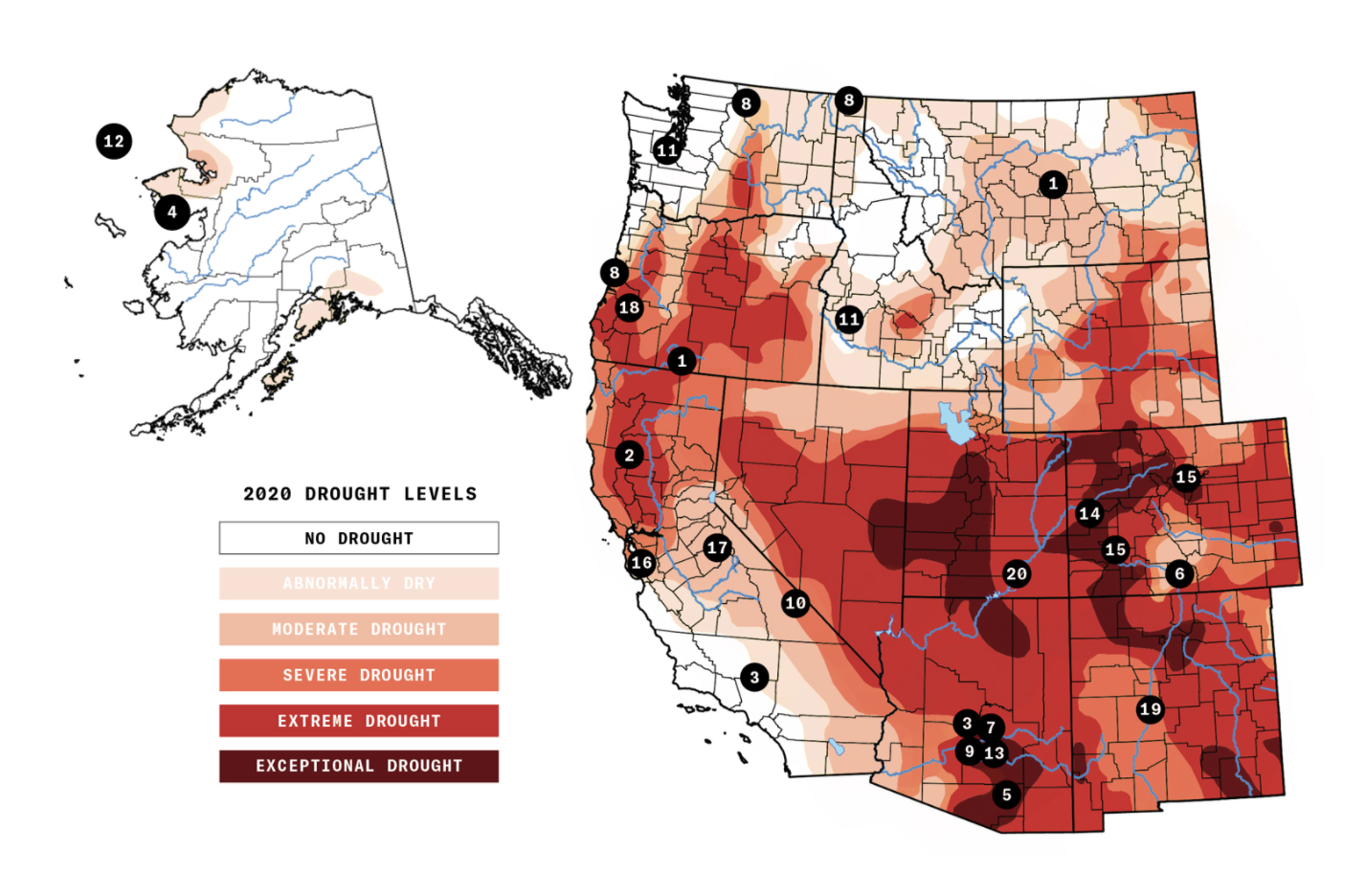

The accompanying graphic includes a few examples of the evidence Newsom mentioned. But then, you only have to step outside for a moment and feel the scorching heat, witness the dwindling streams, and choke on the omnipresent smoke to know that something’s way off-kilter, climate-wise.

But during his September stop outside Sacramento, California, under a blanket of smoke, Trump merely grinned and shrugged it off, again asserting that scientists don’t know what’s happening with the climate. And, anyway, he said: “It’ll start getting cooler. You just watch.”

High Country News

- Lewistown, Montana, (70 degrees Fahrenheit) and Klamath Falls, Oregon, (65 degrees) set high-temperature records for the month of February.

- California had its driest February on record.

- In April, parts of southern Arizona and California saw the mercury climb past 100 degrees Fahrenheit for multiple days in a row, shattering records.

- Nome, Alaska, experienced its warmest May since record-keeping began in the early 1900s.

- Seven large fires burned across more than 75,000 acres in Arizona during May, and in early June, lightning ignited the Bighorn Fire in the Santa Catalina Mountains near Tucson, ultimately torching 120,000 acres. A week later, the Bush Fire broke out in Maricopa County and became the fifth largest in the state’s history.

- On July 10, Alamosa, Colorado, set a temperature record for a daily low (37 degrees Fahrenheit). Later that day, it set another record for the daily high (92 degrees).

- Phoenix, Arizona, set an all-time record for monthly mean temperature in July (98.3 degrees), only to see that record fall in August (99.1 degrees Fahrenheit). The temperature in the burgeoning city exceeded 100 degrees on 145 days in 2020 — another record.

- Westwide in August, 214 monthly and 18 all-time high-temperature records were tied or broken, including in Porthill, Idaho (103 degrees), Mazama, Washington (103 degrees), and Goodwin Peak, Oregon (101 degrees).

- By the end of October, Phoenix had experienced 197 heat-associated deaths — about five times the yearly average during the early 2000s.

- In Death Valley National Park, the mercury hit 130 on August 16, breaking the previous all-time record set in 2013.

- Across the Western U.S., hundreds of monthly and all-time high-temperature records were broken in August, including in several places in Idaho and Washington, where the mercury climbed above 100 degrees.

- Warm temperatures in Alaska caused ice on the Chukchi Sea to melt, leaving record-tying amounts of open sea.

- During monsoon season (June through August), Phoenix received just 1 inch of rain, or about 37 percent of average, and then received no precipitation at all in September or October.

- Grand Junction, Colorado, experienced its driest July and August on record. On July 31, lightning ignited the nearby Pine Gulch Fire, which grew to 139,000 acres, making it (briefly) the largest in state history, only to be eclipsed by the 207,000-acre Cameron Peak Fire in the northern part of the state.

- Colorado’s wildfire season was not only its most severe on record, but most of the fires also burned far later in the year than normal. In mid-October, when Colorado’s mountains would normally be covered with snow, the East Troublesome Fire west of Boulder tore through high-elevation forests and homes to become the state’s second-largest fire ever. Shortly thereafter, the Ice Fire broke out at nearly 10,000 feet above sea level in what was once known as the “asbestos forest” near Silverton, burning over 500 acres.

- A dry thunderstorm that generated more than 8,000 recorded lightning strikes hit Central and Northern California in late July, igniting multiple megafires. The resulting August Complex became the largest fire in state history, and together with the SCU Lightning Complex, the LNU Lightning Complex, and the North Complex fires, it burned across more than 2 million acres, destroyed 5,000 structures and killed 22 people.

- Smoke from California’s fires spread across the region, causing particulate matter to build up to levels that were hazardous to health and significantly diminishing solar energy output.

- In September, several fires were sparked in Oregon’s tinder-dry forests. Fueled by high winds, they went on to burn more than 1 million acres and 4,000 homes.

- In August the Rio Grande in New Mexico shrank to the lowest mean monthly flow since 1973. Other rivers in the region, including the Colorado, Green, and San Juan, ran at far-below-average levels throughout the summer.

- As of early November, Lake Powell’s surface elevation had declined by 35 feet since the same date in 2019, and summer hydroelectric output from Glen Canyon Dam’s turbines was 13 percent below the previous summer’s.