I’m a video producer here at Grist, which means I make a lot of content about solutions to the climate crisis. Whether we’re focusing on geoengineering or urban planning, our goal is always to rigorously evaluate ideas to fix environmental problems, and I’m really proud of our work.

But I’ve noticed our videos have slowly shifted toward a slightly different frame: How can we fix X? It’s a subtle change that implies that we’ll find an answer. Here’s a problem, and producer Jesse Nichols will scour the world to find a solution! As a journalist, it’s my job to find answers and tell the truth. But right now the truth is I feel like I have fewer answers than ever. In the face of overwhelming forces, like COVID or climate change or personal tragedy, it feels disingenuous to say anything right now besides “I don’t know.”

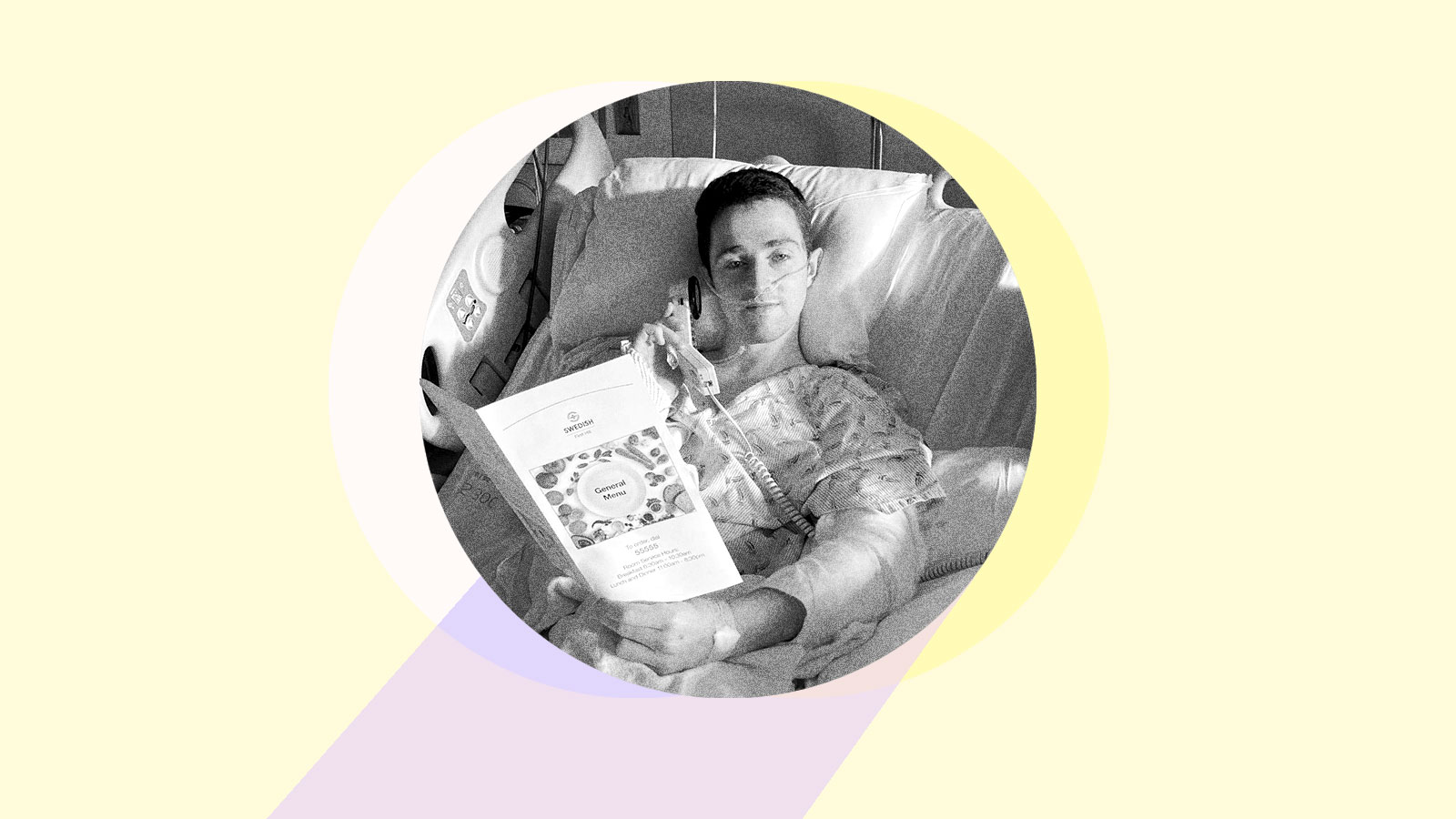

In June, I hit a breaking point — literally, I got into a bike wreck and broke my femur. That afternoon, I’d just finalized a script on how to fix transit. Seven hours later, I was being put under anesthesia for emergency surgery. I had no idea what was coming.

My surgeon described my specific break as one of the worst orthopedic injuries for someone my age (excluding neurological ones like fractures of the spine or head, of course). The hip region gets poor circulation, so healing is precarious. If I had gone into surgery mere hours later, the damage would likely have been irreversible. Even with the timely intervention I received, the doctor gave me 50/50 odds that the bone wouldn’t heal, and I’d need a hip replacement.

Since then, I’ve grown even more aware of just how many answers I don’t — and can’t — have. Two months post-surgery, I still don’t know whether my femur will successfully heal. Six months into the pandemic, we still have no idea when this will be over. My wife is a teacher — her school had reopened with in-person instruction only a day before my bike accident — and we have no idea if or when there might be an outbreak in her classroom. Life is uncertain. To pretend otherwise feels disingenuous.

When I returned to work, that transit script was waiting for me. But suddenly the premise — here’s how to fix X — felt wrong to me. I re-worked that transit script to reflect that uncertainty, and I think it’s even stronger than it was before.

I don’t really know if or how we’re going to get out of all the messes we’re in. I’m just a guy who talks to experts, reads studies, and knows how to use After Effects. Rather than let the weight of that uncertainty derail my life, I’m hoping these realizations will make me a better journalist. But as for what all this means for the long term? I don’t know.