Cara Hoffman was a young reporter in 1994 when she covered an explosion at a chemical plant in Buffalo, New York. She remembers a toxic plume coating nearby lawns in white. Gardens wilted. Pets died, and goldfish floated lifeless in bowls next to open windows. Without an evacuation plan, people in the neighborhood went on with their lives, scrubbing the toxic remnants off their cars.

Hoffman knew Buffalo was an industrial town, but she was shocked by just how much power the industry had, and that it was using that power to ruin people’s lives. The chemical industry tried to deflect the blame for cancer clusters and hide environmental impact statements, according to Hoffman, even while people were getting sick, having miscarriages, and losing family members to illness. After the explosion, the neighbors banded together to form a community alert network. “These things were happening largely to people who lived in poor and Black neighborhoods — places where the deadly ethical failings of a chemical plant would go unnoticed,” she wrote in a reflection.

Hoffman spent years investigating these kinds of environmental crimes before turning to writing fiction professionally in the late 2000s. Today, she writes children’s books. But in a way, she’s still writing the same kinds of stories — they’re just a lot more playful and hopeful.

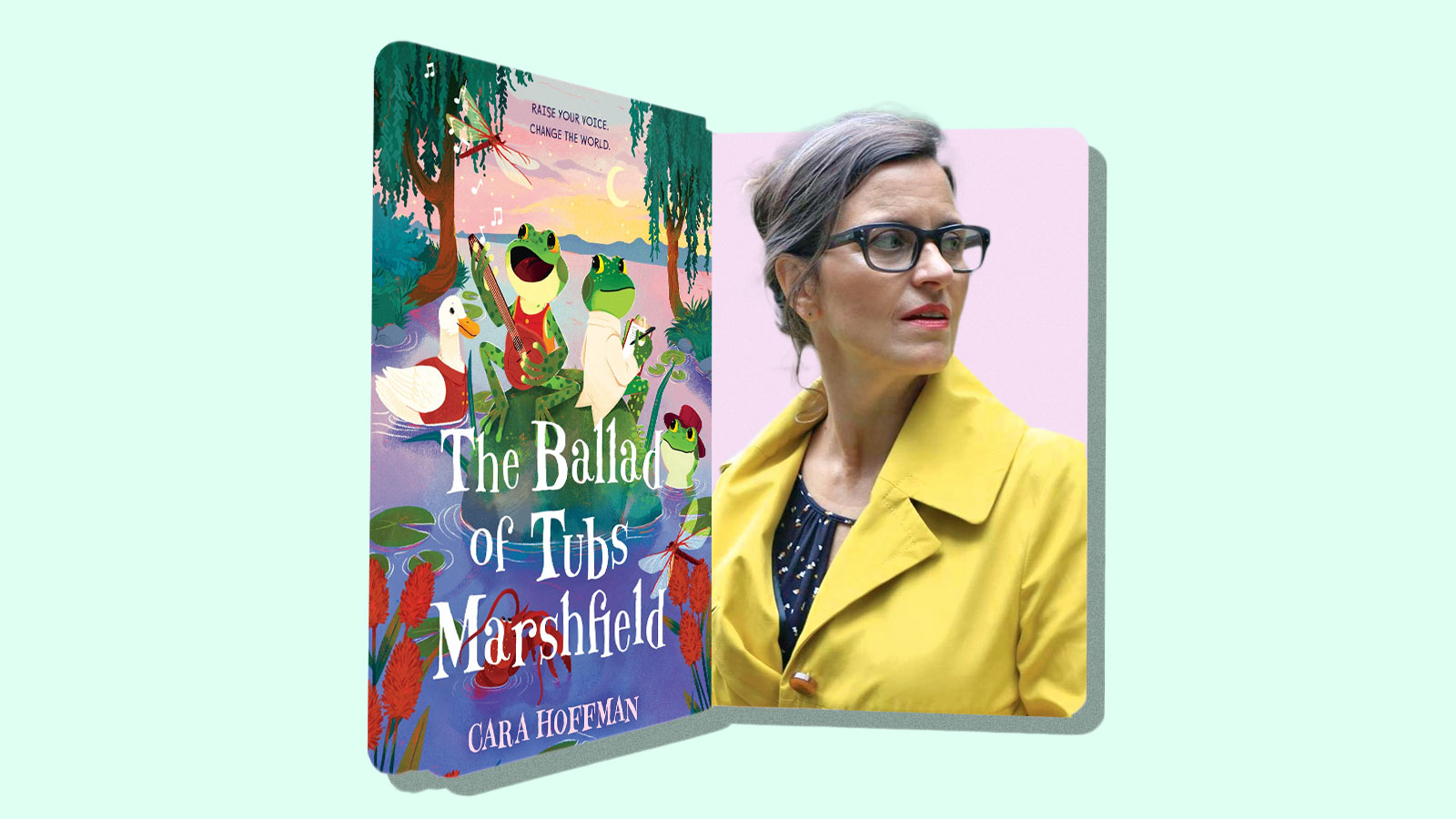

Her newest book, The Ballad of Tubs Marshfield, stars a singing, piano-playing frog named Tubs. His fellow marsh-dwellers, frogs and birds alike, are suddenly afflicted with a mysterious sickness. (No, it’s not COVID-19.) Tubs goes on an adventure to discover the source of the illness: all the industrial waste pouring into the marsh from a nearby factory.

“All of my work has to do with class and the environment, in one way or another, and certainly my children’s books,” Hoffman said.

She has written for all ages, from young adults books to her award-winning novels for adults, like So Much Pretty (2011). She released her first children’s book, Bernard Pepperlin, last year.

I wanted to learn about Hoffman’s past reporting and how it informs her work as a children’s author today. So I called her up, one environmental journalist to a former one, to get her thoughts on how to write for kids when you’re worried about the future. Our conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Q. Your previous work as an environmental journalist sounds really intense. It reminds me of the dramatic image of the job that I got from watching movies like Erin Brockovich. Thinking about what I do as a journalist — like, I’m just sitting here at home on my computer. Is that ridiculous?

A. I think that’s because people are dealing with much bigger issues right now. Younger folks who are working on this stuff are really focused on climate, right? As everybody should be, because this is the ultimate existential crisis of our time.

The environmental reporting I did had to do with specific communities, specific polluters, looking at different places in the Rust Belt and in northern Appalachia. There are places where there’s Manhattan Project waste buried, for example, beneath a trailer park. Northern Appalachia is a dumping ground for all kinds of industrial waste.

Later, I worked a lot around issues with industrial agriculture. It’s actually shocking to think of — I can only call it the depth of depravity — of some of the corporate decisions people have made. For example, I covered a story where fertilizer for fields was actually manufactured from industrial sewage. So it was super toxic and spread over massive amounts of acreage in rural areas. And of course, got people very, very sick. It was marketed as something called “Enviro Green.”

Q. So how did you start writing children’s books?

A. I really love writing for children, and I wanted to do something that wasn’t so heavy. The idea of writing about talking mice was fantastic. And so for Bernard Pepperlin, I created a revolutionary underground network of animals fighting weasels that move to Manhattan from Ohio and are trying to stop time.

When I think about the children’s books that I really loved, by E.B. White and Roald Dahl, joy was a huge part of the underlying message. We need to give children the best chance that they could possibly have to deal with these things and fight them. And the biggest aspect of that is letting them experience a feeling of agency and joy. I think that’s why I made the switch to children’s writing.

Q. The kids who are reading your books are going to be seeing a lot of catastrophic elements of climate change by the time they’re adults. How does that change how you’re writing for them?

A. Oh yeah, absolutely. The message in The Ballad of Tubs Marshfield is that we need continuous direct action in order to turn things around. We can’t be excited about one success, really — we have to understand that we have to be excited, always, to work together, and to continuously be holding government and industry accountable. It sounds really dry, explaining it that way. It works out better when it’s frogs attacking a factory.

These are the kids that are going to be dealing with this crisis. I have a son who’s grown, and I have two stepsons who are teenagers. So the impetus for Tubs Marshfield was having a conversation with my younger stepson about the sixth mass extinction. It’s pretty awful, talking to children about these things and trying to get them prepared for it. It’s something that parents and grandparents are dealing with all the time.

And you don’t want to have a book that’s scary to children. You want to have a book that makes them feel agency and power, and that their own spirit and their own intelligence can lead to something good. They are resilient. We’re certainly never going to go back to where we need to be, as far as the environment is concerned. But I think it’s super important for all of us who are working in media to understand the depth of the crisis and how we can communicate these things to children so that they’ll be able to be revolutionaries in their own lives.

Q. I want to talk more about your new book, Tubs Marshfield, because it’s such a striking example of an environmental justice story, but for kids. There’s the people of the marsh looking for scapegoats, and then coping with music and ways to find joy in tough times, and then the marsh community actually discusses managed retreat and decides to fight back at the industry. Did you intentionally include all of this, or did it subconsciously appear as you were writing it?

A. No, no, they’re all intentional. The message is about mutual aid, solidarity, and tactics. That diversity of tactics is something that’s super important to teach people. I think that’s really the foundation of what I was doing here: We’re using art, we’re using science, and then everybody’s using their individual wits, and everybody is also cooperating. It’s about being able to work with people who we don’t really agree with. We don’t have to like each other, and we don’t have to agree on everything — but we do need to understand that we all live here, and that we can help each other.

Q. What kind of responses have you gotten to Tubs Marshfield from kids?

A. I got my first fan letter, which was really exciting. I got people sending pictures of their kids reading it excitedly. I really love writing for children because they immediately emotionally respond to the book. You know, they’re pestering their parents to read another chapter and to not put it down. I think that makes me happier than anything, the responses from children.

In Bernard Pepperlin, I wrote a bunch of songs that went with it. And some kid came to a reading and must have been 6 or 7, and he was off his gourd about memorizing all the songs and dances. He’s just jumping around the couch, singing these songs all day. And that to me is the absolute best thing that could ever happen. You’ll never get that kind of response from an adult.