This essay was first published in our semi-weekly newsletter, Climate in the Time of Coronavirus, which you can subscribe to here.

A few weeks ago, I got sick. My whole body ached so persistently that the only place I could really be comfortable was in a bath, which isn’t really sustainable over long periods of time unless you’re one of those merpeople. My lymph nodes protruded so far out of my neck that the skin around my jaw felt tight and painful. I was so tired I ended up sleeping between 12 and 18 hours a day.

While I was writhing around between my couch and my bed, the only other human I’d seen up close in a month told me that he’d been diagnosed with COVID-19. So the coronavirus had in all likelihood found me!

I thought I had protected myself reasonably well — mask on, limited trips to the grocery store, a few walks on quiet streets, and seeing exactly one(!) other person. That felt safe enough; we both lived alone, worked from home, didn’t see anyone else barring basic errands. I thought I was being smart and cautious, taking what felt like a small, garden-variety risk to sustain just enough human interaction to keep me reasonably sane. But it turns out there’s no place you can be truly “safe” from coronavirus.

As Grist’s advice columnist, a substantial percentage of the questions I receive are from readers seeking certainty about the threat of climate change. What will happen? When will it happen? Where will it happen? And what can I do to ensure that it will not happen to me? It is a completely reasonable human response to a huge, difficult-to-comprehend threat. You want to know how to protect yourself; what the risk to you is.

I don’t attempt to answer any of those queries. There is no way to do so; these readers are seeking an impossible assurance. Climate change and coronavirus are inescapable for the same reason: They will each transform society, wholly and against our will, and humans can do our very best to prepare and adapt. But even with the very best preparation and adaptation, the utmost cautiousness, you have no idea what or when or where you will experience its impacts.

I think every generation believes they are living through unprecedented change, and I don’t think mine is particularly special. This change, the pandemic, is certainly really sudden and strange. The warming climate isn’t sudden at all, and yet it’s no less threatening. I will continue to do my best to prepare for and adapt to and mitigate, where I can, the impacts of climate change. I thought I had done what I reasonably could to mitigate — at least for myself — the risks of contracting coronavirus, and that went out the window so spectacularly I have to laugh.

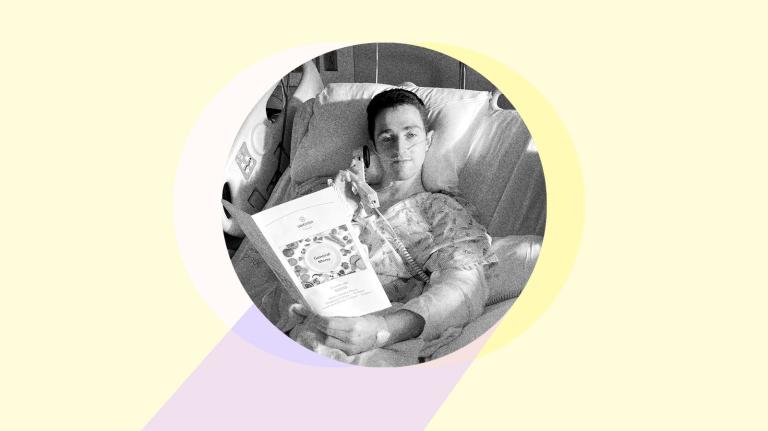

All things considered, I was fortunate. After three days of feeling wretched, I feel completely fine now. My friend’s experience was much worse. Our illnesses started on the same day, but his symptoms were more severe and lasted much longer. I waited fretfully for his symptoms to subside, prickly with the guilt that I had had it so much easier.

I’m aware we were both lucky to recover at all.

I might never be 100 percent certain that I ever actually had It, as I was denied a test (my doctor said I’m young, healthy, and my treatment would have been the same regardless) and antibody tests remain elusive. But why does it matter to me now? The promise of immunity, of course, of some form of protection; that it’s over, I faced the threat, it was fine, and now I no longer have to worry. The badge of having survived COVID unscathed is perhaps the most coveted security blanket of the moment.

And yet, I am under no illusion that I have any real power over what’s coming, with regard to climate change. and I don’t really think that was ever the goal. Who has ever been able to control the future, anyway? But please do not misunderstand that to be an expression of nihilism or defeat. I have not given up, to the contrary; I am ready for a future that I know I cannot imagine.