A gender reveal party gone awry in California last week sparked a wildfire that consumed more than 13,000 acres in five days. On Thursday, researchers at the U.S. Climate Prediction Center revealed the gender of a weather phenomenon that is likely to be even more destructive. A La Niña weather pattern has officially formed. The conditions that led to the pattern’s formation have already influenced this year’s unprecedented hurricane and wildfire seasons.

La Niña and El Niño are weather patterns that influence global temperatures and precipitation. An El Niño forms when there’s warmer water in the Pacific Ocean. It often produces a less busy Atlantic hurricane season by dredging up cooler water in that ocean. A La Niña does the opposite: It forms when the surface of the Pacific cools. The result is usually fewer storms in the Pacific Ocean but more in the Atlantic.

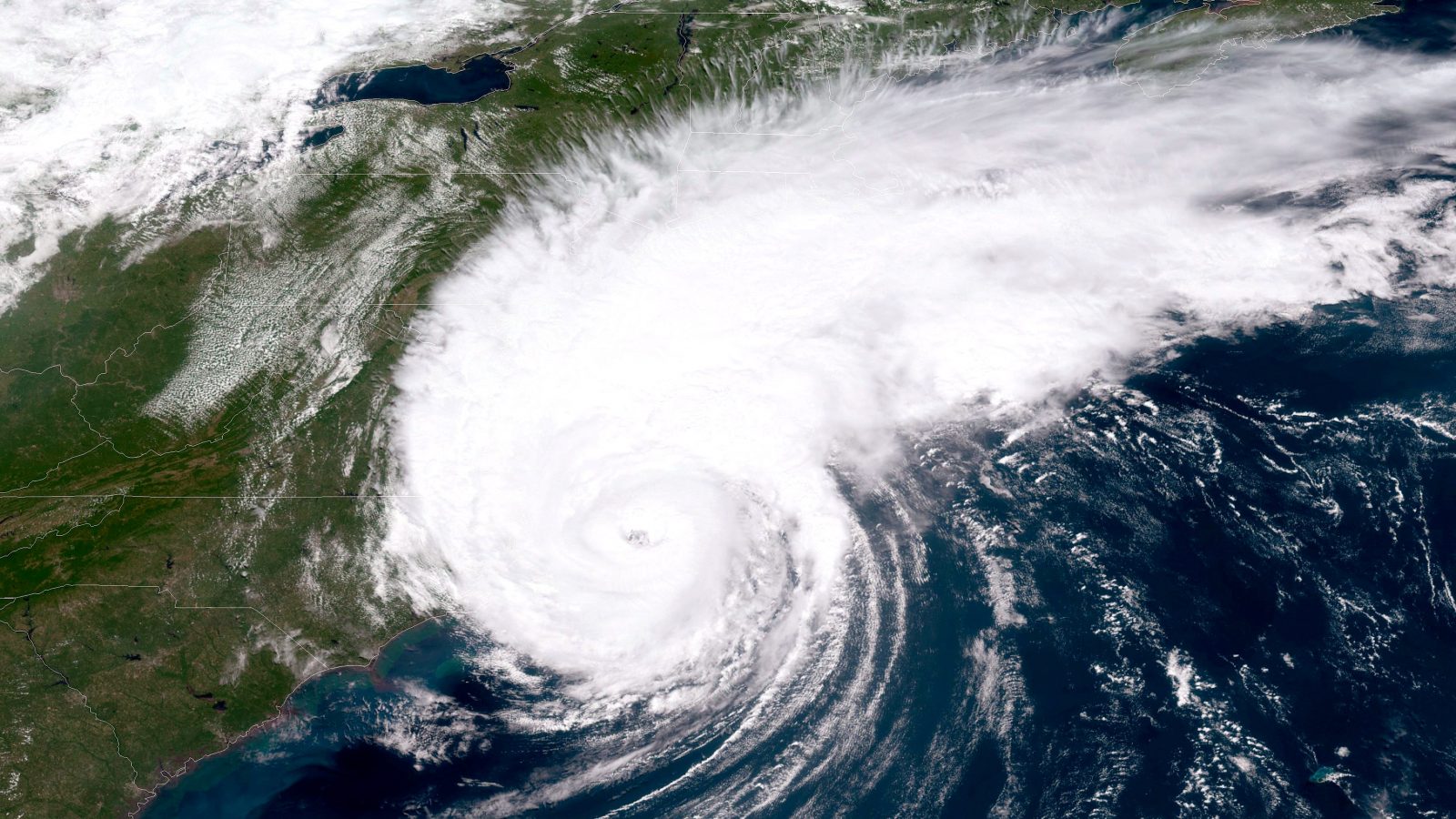

The formation of a La Niña this year isn’t a surprise. Hurricane forecasts issued back in April factored in the probability of a La Niña forming, and some models showed the possibility of cooler temperatures in the Pacific as early as March. Last month, NOAA ratcheted up its total hurricane season forecast to between 19 and 25 named storms, including seven to 11 hurricanes, to account for the increasing likelihood of a La Niña. (The agency has never predicted that many named storms before.) The abnormal season forecasters predicted has come to pass: The Atlantic has spawned tropical storm after tropical storm this year, most of them the earliest on record.

“We expected there to be a weak La Niña since last spring,” Dan Kottlowski, AccuWeather’s lead hurricane expert, told Grist. “This is the reason why we’ve been forecasting a very active season. Whatever impacts that are created as this La Niña develops are already occurring.”

The big unknown, Kottlowski says, is how long the hurricane season will last. When there is an evolving La Niña like there is now, the hurricane season can continue all the way into December or even January. That’s what happened in 2005, the year Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast. That hurricane season spawned 28 named storms, and the last tropical storm of the season, Zeta, formed a full month after the official end of the season. A longer hurricane season creates not only the potential for more storms but also a higher likelihood that some of those storms will hit the continental United States.

A La Niña can have other climatological effects, too. The winds exacerbating the wildfire season out West right now are more proof that a La Niña is in effect, Kottlowski says. California is having its worst wildfire season on record, the result of a mixture of factors that include climate change, dry weather produced by La Niña, and a century of bad forest management. In a few months, the La Niña could produce a colder and wetter winter across the northern U.S. and an abnormally dry winter season in the South and Southwest.

Right now, Kottlowski has his eye on the disturbances and storm systems brewing in the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico. “Especially during the month of September and maybe even October, a La Niña will favor even more tropical development,” Kottlowski said. “If you live anywhere along the [Gulf] Coast and the Atlantic basin, be prepared for another hit this season.”