Every 10 years the United States government endeavors to do something miraculous — a count of every human being living on U.S. soil. This survey of the population, known as the decennial census, is one of the foundations of American democracy. It helps us track changes in how many people live in different areas, so that representation in Congress reflects reality. It is the statistical backbone for academic research, city planning decisions, and the distribution of government funds. And all of these functions have serious implications for environmental justice and climate policy.

Data collection for the census kicked off a few weeks ago, just as coronavirus began to rear its ugly head in the U.S. The Census Bureau goes to great lengths to make sure every person is counted, but some experts are worried that COVID-19 will crowd out these efforts, in more ways than one.

Eric McGhee, a senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California, told Grist that on a scale of one to 10, his concern for the 2020 census is at about an eight or nine. After an initial self-response period where people can fill out the form online, by mail, or by phone, the Bureau sends out field workers to start knocking on doors of non-responders. Already, field operations have been twice delayed by the epidemic, and with the ongoing spread of coronavirus, additional delays are possible.

McGhee’s biggest concern is that the virus will overshadow the whole process. “The census can’t really get its message out the way it was expecting to,” he said. “Both because it’s hard to do the physical outreach that it was planning, but also because any media campaign is going to get totally swamped by COVID news.”

Less awareness about the census could lower the initial response rate, which could create all kinds of problems, like a more expensive followup program and an inaccurate count. If the count is delayed long enough, it could even potentially mess up the schedule to redraw districts in time for the 2022 primaries.

A flawed census count would have ripple effects on environmental justice and plans to tackle climate change. When polluting companies seek emissions permits, they often have to perform risk assessments based on census data to estimate the increased risk of health problems in the surrounding area. Researchers trying to better understand the public health impacts of lesser-studied contaminants like PFAS use census data. City planners looking at how climate change will affect different neighborhoods so they can develop adaptation strategies rely on census data. An undercount will skew the results in all cases, potentially downplaying how communities have been or will be affected.

Cara Brumfield, a senior policy analyst at the Georgetown Center on Poverty and Inequality, said groups that have historically been hard to count under normal circumstances include people of color, recent and undocumented immigrants, and people experiencing poverty and/or homelessness. “Lots of vulnerable populations are considered hard to count in the census, and of course, being undercounted or missing in the census puts that community at even more of a disadvantage,” she said.

These are also the same populations who are most vulnerable to the more dangerous aspects of climate change, like severe storms, flooding, and extreme heat. Because these events are becoming more common, “The stakes are higher than ever to have those folks represented in our democracy,” said Denice Ross, a senior fellow at the National Conference on Citizenship, a nonprofit. “If you have networks where you can encourage people to get out the count and fill out the form, this is the time to be using those digital networks.”

Undercounted communities could ultimately miss out on key federal dollars relevant to climate adaptation and mitigation. The census determines allocation of funding for programs like the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program, which helps low-income households pay for energy efficiency upgrades and other changes that will lower their heating and cooling bills, as well as their emissions. Other examples include funding for mass transit and a program that funds water infrastructure projects, including stormwater drainage in rural areas, which will become increasingly important as storms intensify.

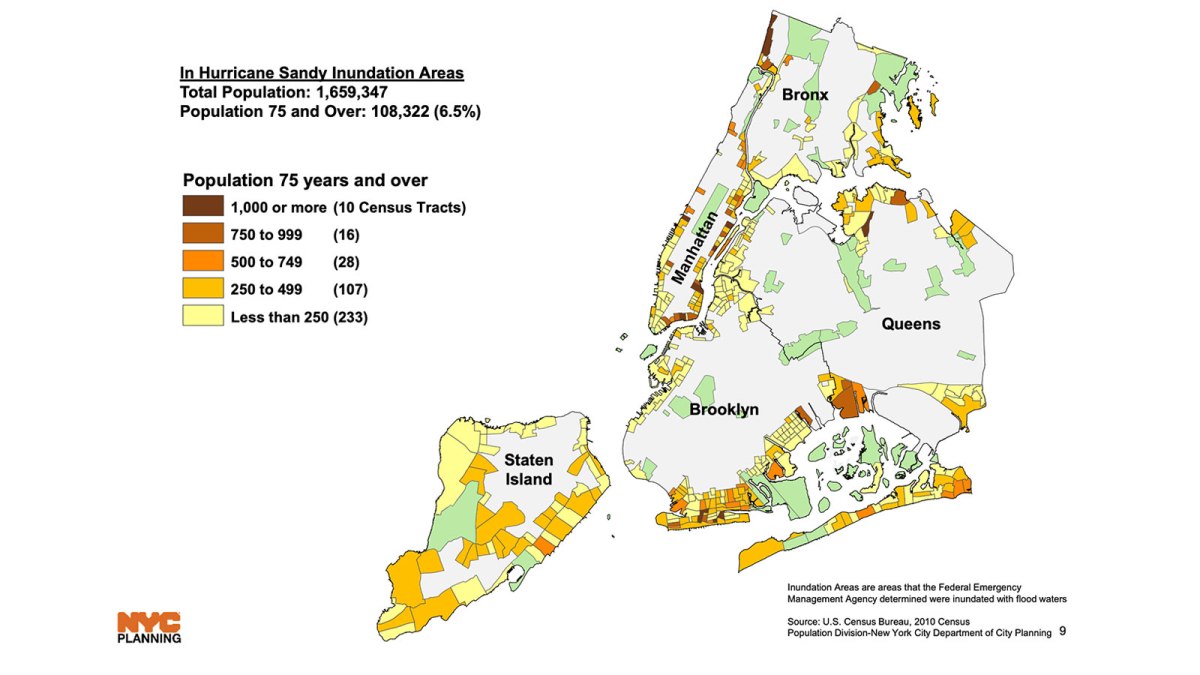

NYC Planning

Census data also provides a granular demographic picture of a region that is key to emergency preparedness. After Hurricane Sandy hit New York City, the Department of City Planning studied the neighborhoods that were inundated. Using census data, the department identified areas with high concentrations of people over 75, a population that also has a large number of people with physical disabilities, and used that information to make sure that emergency shelters were accessible and to determine how many buses would be needed for evacuations.

The census is the cornerstone of myriad other community planning initiatives related to climate change. For municipalities developing adaptation plans to sea level rise, it informs zoning changes and tough relocation decisions. Transportation planners use census data to design more effective bus routes and bike routes, which can reduce emissions from vehicles. Cities with climate targets use it to understand changes in their greenhouse gas emissions. Population growth is one of the biggest drivers of emissions increases, so seeing which parts of a city are growing and by how much can help determine where to prioritize emissions-reduction programs and resources.

Joseph Salvo, Chief Demographer at the NYC Department of City Planning, pointed to another critical aspect of taking on climate change at the city level: representation.* Funding and programs are a reflection of the legislative priorities of members of Congress and state legislatures, and the census determines how seats are allocated. “We need people who are fighting for these programs to protect the hundreds of miles of shoreline that we have in New York City,” Salvo said. “Without that legislative push, the money doesn’t come, because the programs never get created.”

Since this year’s count began in mid-March, about 41 percent of all households have responded. In 2010, more than half of households had responded by April 1 — and back then, they couldn’t even fill it out online! As of now, U.S. residents have until August 14 to respond.

So what are you waiting for? Go fill out the census!

Correction: We originally identified Joseph Salvo as director of the population division at the NYC Department of City Planning. Grist regrets this error.